The newfound popularity of emojis and emoticons can be attributed to the human need for nonverbal communication, representing language progression and evolution. They serve to imbue digital writing with imperative nonverbal cues that would otherwise be lacking.

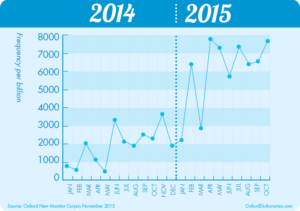

For the first time in history, Oxford English Dictionary (OED) “Word of the Year” is not a letter-composed word, but rather an emoji: 😂. OED picked 😂 because of the dramatic increase in the usage of this pictograph in 2015 (See Figure 1; Oxford Dictionaries).

Both emojis and emoticons are relatively new phenomena, and the bulk of peer-reviewed research is on emoticons as they have been around longer. Alex Hern, a technology reporter for The Guardian, explains the difference between emoticons and emojis. Emoticons are keyboard symbols combined to make pictures, often faces. For example, this is a smiley emoticon: “:),” this is an open mouthed emoticon “:O,” and this is a heart emoticon “<3.” Emojis are small pictures that were first created by Shigetaka Kurita in Japan during the late 1990s. The emoji library has evolved and expanded since its inception and now includes pictures of faces, food, animals, and more. Here are some examples: 🙋 , 😜 , 💩 .

Though emojis are a relatively new invention, the use of pictures in communication dates back to the Neanderthals (Newman). Roughly 40,000 years ago, Neanderthals made parietal art, cave paintings, to display stories. They painted murals of bison, humans, and other animals to communicate to “hunting gods.” From 3500 BCE to 400 CE, the Egyptians created a complex system of hieroglyphics, used by civil officials to record history and laws, by priests to write prayers, and even by artisans as decoration (Scoville). Egyptian hieroglyphics have striking similarities to emojis. In Figure 2, look at the hieroglyphs for “man,” “sun,” and “king.” Now look at the respective emojis: 🚶, 🌞, 👸 . Some see these parallels as proof of language devolving: “After [a] millennia of painful improvement, from illiteracy to Shakespeare and beyond, humanity is rushing to throw it all away. We’re heading back to ancient Egyptian times” (Jones).

But their use in modern times is not a sign that society is regressing in its communication skills. Rather, it represents an advancement of those skills. Jones fails to note that hieroglyphs were incredibly advanced and extremely effective for communicating, especially with people of all social statuses. Hannah Goldfield, writer of the New Yorker article “I Heart Emoji,” believes that emojis are proof that language is progressing. “Emoji has expanded the definition of texting,” she writes.

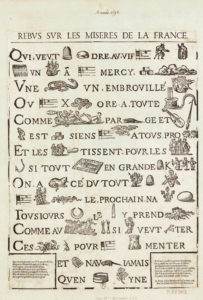

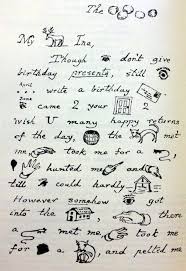

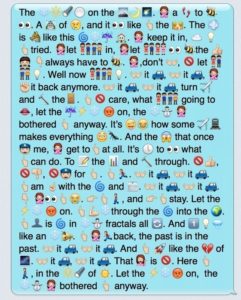

Emojis and emoticons also derive from the ancient rebus. The word “rebus” is from a Latin tag “non verbis sed rebus” — “not with words but with things.” The Egyptians used rebuses in their writing, and so did Leonardo da Vinci, Ben Josen, and Lewis Carroll.

The pictures in Figure 3 serve as visual comparisons, revealing the similarities between past uses of rebuses in writing and the current use of emojis in text messaging. On the far left is a French text written in 1592. Those who don’t speak French can still follow along, seeing familiar images, for example, of music, people, and castles. The middle picture is from a letter that Lewis Carroll, author of Alice in Wonderland, wrote to a friend. He uses drawings to represent words. For example, the deer represents the word “dear.” Throughout the letter, Carroll gives off a cheery tone, which is conveyed by his endearing drawings. His ability to convey tone with rebuses suggests that emojis might also convey tone. On the right side is a modern screenshot of a text message that uses emojis to represent the lyrics of “Let it Go” from the Disney movie Frozen. It looks very similar to the past writings, and as with the French text, even if you don’t know the lyrics, you can decipher the meaning.

The rebus reminds us that the usage of emojis as word substitutes is not a new idea, but rather a literary technique that is making a swift comeback to provide a more universal means of communication.

Natural language is rarely accompanied by speech without emotional context or physical gestures, making it multi-modal. Emojis help writers convey thoughts and feelings digitally by filling the void for facial expressions that enhance verbal communication. Charles Darwin, the famous anthropologist, found that facial expressions of emotion are universal, not learned differently in each culture. He concluded that all humans are anatomically alike and use their muscles similarly to express feelings. Subsequently, common facial expressions are often universal, and the emojis that represent them can be used to communicate emotion universally.

In “Emoticons in Computer-Mediated Communication: Social Motives and Social Context,” researchers argue that emoticons help with communication because they substitute for natural communicative facial expressions (Derks, Bos, Grumbkow 99). “Emoticons,” the researchers write, “may serve as non-verbal surrogates, suggestive of facial expressions, and may thus enhance the exchange of emotional information by providing additional social cues beyond what is found in the verbal text of a message” (99). Text is often devoid of the non-verbal expressions, but that omission is rectified through the use of emoji and emoticon symbols.

By combining the universality of the visual imagery that represents nonverbal communicatory cues, pictographs are a viable form for cross-cultural communication. As Goldfield writes, “Most Emojis are universally understood” This is supported by recently released Instagram data regarding the percentage of texts found on the app that contain emojis. It broke the information down by country, as shown in Figure 4, revealing that usage and frequency of emojis spans many different countries. The majority of the countries speak different verbal or written languages, but they all use emojis in the same way, indicating their universal usage across the human spectrum.

Junichi Azuma and Hermann Maurer discuss the possibilities of emoticons being used to create a new global form of communication. They conclude that “[I]f the trend of the replacement of linguistic units by graphic emoticons seen in the communication behavior of young Japanese people goes further, we will be able to devise universal symbolic signs that will work as a special kind of auxiliary language used for communication using computers, mobile phones, and other communication-based instruments” (116). Just nine years after this article was written, we now have an extensive library of hundreds of emojis and software with thousands of emoticons. The accelerated progression signifies that Azuma and Maurer’s prediction is on track. Pictographs are quickly becoming a universal visual language. Azuma and Maurer propose future uses of pictographs: “Even the people who speak different languages will be able to communicate through email just by using the symbolic signs and a meeting in the multilingual situation will be much easier because of the new type of symbolic language.” (122).

Emotional intelligence is the ability to express your emotions effectively and to understand others’ emotions in social settings. It is said to be more important than IQ to success, and the most important factor in social awareness (Bradberry). But what does it have to do with emojis? Many emotional intelligence cues are lost in writing, such as body language, vocal pitch, and facial expressions. Emojis reintroduce these cues, which have been lacking or are often more difficult to convey in traditional written text.

Writing has, to an extent, been overcoming the lack of nonverbal cues for centuries. For example, the majority of people who read Shakespeare would not claim that his writing “lacks emotion.” He employs rhetorical strategies — metaphors, counterpoints, allusions — to develop pathos. Though these techniques are effective for embedding emotional cues into language, the majority of us are not writing novels or Shakespearean sonnets, so having emojis allows us to easily put nonverbal cues into digital writing. Derks quotes the computer-mediated communication researcher, Fischer, who explains that “the fact that people do use emoticons shows that they apparently need some sort of short string displays of emotions.”

Emojis are quickly becoming ubiquitous in digital language because they convey emotional complexity, which can be difficult to translate into words. Joanna Stern, a personal technology columnist for the Wall Street Journal, writes that when “switching from ☎ and 👫 communications to primarily 📄 , we have lost out on the feelings that can only be conveyed in inflection and 😊 😝 😂 😣 😭 😥 😩 😮 . ” Stern explains how she went from being an emoji skeptic to an emoji lover. “When I started to embrace [emojis],” she writes, “I felt in some peculiar way that my text messages had more emotion. … I can convey my bad mood about having to work on Sunday with just a 😡 or my excitement for my sister’s landing a new job with not one 😍 but 😍 😍 😍 😍 😍 😍 😍 😍 . ”

I was interested in how effective emojis are as a form of pathos, so I created and conducted a research survey, “Emojis in Texts.” It was sent out to Stanford’s Class of 2019, and more than 100 first-year students participated. Part one gave the students screenshots of variations of the text message “no,” and asked them to rank the tone of the message on a scale of one to five (one being extremely negative and five being extremely positive). Each message contained only one word, “No,” but each was punctuated differently or contained different emojis. The results showed that the use of a single emoji can drastically change the tone of a message. The average ranking given to the text “No…” was a 2.02, whereas the average ranking given to “No…😊 ” was a 3.95.

The data from the second part of my survey reveals that emojis are also useful for readers in understanding the emotional context of messages. One of the questions in part two read, “Which text message made you feel the most emotionally connected to the texter?” and students were given a list of text messages from which to choose. The top three answers were all messages that contained emojis, which aid empathetic feelings and bolster communication on an interpersonal level.

The texting phenomenon, such as abbreviating words, creating acronyms, or using pictograms, is neither “especially novel nor incomprehensible.” David Crystal, a British linguist, says that “All the popular beliefs about texting are wrong or at least debatable. … There is increasing evidence that it helps rather than hinders literacy.” He argues that people like Jones — who suggests “We are evolving backwards” — are language conservatives, afraid of embracing change (53). Recent language changes introduced by texting are not something people should be worried about; if anything, new forms of language, like the emojis and emoticons, are proof that communication methods are still evolving, as they have since the inception of language.

Writing has transformed so much recently that some argue that the budding generation of millennials has an entirely new form of writing. Stanford’s Andrea Lunsford conducted a study in which she collected thousands of pieces of in-class and “life” writing from students. She concluded that students are “writing more than ever before in history” but are now focused on “instantaneous communication” (Haven). Lunsford’s argument denotes that digital writing, like text messages, blog posts, and Tweets, represents a new genre of writing and should be treated differently.

When conducting my research study, I aimed to discover results relating to the emotional appeal of emojis, but I discovered something about the nature of texting that I did not anticipate. I was surprised to see that the most negatively ranked text message, with an average of 1.8, was simply the word “No.” Originally, I included this message as a control because I assumed that this message, grammatically correct and free of abstract punctuation or emojis, would have a neutral ranking. The results, however, reinforced Lunsford’s argument. The writing of today is different from the writing of the past. What might be a neutral sentence in an academic paper takes on an entirely different tone in a text message.

Interestingly enough, the closest neutral-ranking text messages all contained emojis. My conclusion drawn from this observation is that texting is a form of social-emotional communication; thus people expect emotional cues to be an innate part of writing. A text message portraying some form of emotion through emojis is subsequently considered more “normal” than a message without emotional cues. Text messages are terse, lacking context or explanation and often sounding harsh. To remedy this and to make these sentences neutral, we can use emojis as a new, natural, and quick rhetorical device to convey ideas and feelings.

The use of emojis in text has become ubiquitous. Domino’s even lets you order a pizza now via tweet with just a “🍕 .” The more writers use symbols and pictograms, the greater the debate will grow over whether these characters are enhancing or inhibiting communication. Though some linguists lament and decry that their use has resulted in an emerging language that they fear will displace English, their fears are unfounded. The continued integration of emojis into text is part of a natural progression and evolution in the development of human communication. The benefits for their use in future communication will be limited only by human ingenuity. Perhaps Azuma and Maurer are correct to suggest that “in the future, public signs, instructions for vending machines, automated teller machines or other interactive machines will all use the universal symbolic signs” (122).

Emojis and emoticons are not a regression to the Stone Age, but a leap forward toward the creation of a universal mode of communication. Pictographs are digital writing’s newest rhetorical device, allowing us to embed important communicative cues into our writing through 😁 🙌 😂 ! We are meshing 📝 language with 👀 language to communicate ideas and feelings. The possibilities for this visual language are vast, but for now, I encourage you to experiment with emojis in your 📱 💻 writing and to find new ways to break nonverbal and language-based communication barriers through 😁 😂 😃 . Maybe our ancestors were onto something after all.

:::

Grace O’Brien is a freshman at Stanford University studying computer science and product design. After spending her last summer as a Google CSSI student, she’s become excited about all-things technology. She enjoys finding the intersection between technology and the humanities, as shown in this article. This summer, she’s excited to dive into learning more about computers as a Microsoft Intern. In her free time, Grace loves traveling,

writing, and spending time at the beach.

Works Cited

“Ancient Scripts: Egyptian.” Ancient Scripts: Egyptian. Lawrence, Lo., n.d. Web. 04 Dec. 2015.

Azuma, Junichi, and Hermann Maurer. “From Emotions to Universal Symbolic Signs: Can Written Language Survive in Cyberspace?” Institute of Information Processing and Computer-Supported New Media. Part of the Faculty of Science, Graz University of Technology., 2007. Web. 21 Nov. 2015.

Bradberry, Travis. “Why You Need Emotional Intelligence To Succeed.” Forbes. Forbes, Inc., 7 Jan. 2015. Web. 2 Dec. 2015.

Crystal, David. Txting: The Gr8 Db8. 2008, Oxford.: n.p., n.d. Print.

Darwin, Charles. The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. Chicago: U of Chicago, 1965. Print.

Derks, D., AE Bos, and J. Von Grumbkov. “Emoticons in Computer-mediated Communication: Social Motives and Social Context.” PubMed. MEDLINE, 14 Feb. 2008. Web. 11 Oct. 2015.

Derks, Daantje, Arjan E.R. Bos, and Jasper Von Grumbkov. “Emoticons and Social Interaction on the Internet: The Importance of Social Context.” ScienceDirect. N.p., Jan. 2007. Web. 4 Dec. 2015.

Dimson, Thomas. “Emojineering Part 1: Machine Learning for Emoji Trends.” Instagram. 2015 INSTAGRAM, Apr. 2015. Web. 22 Oct. 2015.

“Emotional Intelligence.” Psychology Today. Sussex Publishers, n.d. Web. 2 Nov. 2015.

Evans, Vyvyan. “Beyond Words: How Language-like Is Emoji?” Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press, 20 Nov. 2015. Web. 25 Nov. 2015.

Goldfield, Hannah. “I Heart Emoji.” The New Yorker. Condé Nast, 16 Oct. 2012. Web. 15 Nov. 2015.

Haven, Cynthia. “The New Literacy: Stanford Study Finds Richness and Complexity in Students’ Writing.” Stanford News. Stanford University, 12 Oct. 2009. Web. 11 Nov. 2015.

Hern, Alex. “Don’t Know the Difference between Emoji and Emoticons? Let Me Explain.” The Guardian. 2015 Guardian News and Media Limited, 6 Feb. 2015. Web. 20 Nov. 2015.

History.com Staff. “Oxford Dictionary Debuts.” History. A+E Networks, n.d. Web. 25 Nov. 2015.

Jones, Jonathan. “Emoji Is Dragging Us Back to the Dark Ages – and All We Can Do Is Smile.” The Guardian. 2015 Guardian News and Media Limited, 27 May 2015. Web. 12 Nov. 2015.

Jouvenal, Justin. “A 12-Year-old girl is facivng criminal charges for using certain emojis. She is no alone.” Washington Post. Web, 27 Feb. 2016.

Kottke, Jason. “Emoji Rebus Puzzles.” Web log post. Kottke.org. N.p., 9 Jan. 2014. Web. 2 Nov. 2015.

Leminh, Trang. “Your Favorite Disney’s “Frozen” Lyrics Reenacted In Emojis.” BuzzFeed. 2015 BuzzFeed, Inc, 24 Feb. 2014. Web. 15 Nov. 2015.

Newman, Judith. “If You’re Happy and You Know It, Must I Know, Too?” The New York Times. The New York Times Company, 21 Oct. 2011. Web. 1 Dec. 2015.

Oxford Dictionaries. “Oxford Dictionaries Word of the Year 2015 Is….” Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press, 16 Nov. 2015. Web. 18 Nov. 2015.

Scoville, Priscila. “Egyptian Hieroglyhs.” Ancient History Encyclopedia. Ancient History Encyclopedia Limited, 2 July 2015. Web. 4 Nov. 2015.

Speer, Rob. “Emoji Are More Common than Hyphens. Is Your Software Ready?” Web log post. Luminoso Blog. WordPress.com, 4 Sept. 2013. Web. 4 Nov. 2015.

Stern, Joanna. “How I Learned to Love Writing with Emojis.” The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company, Inc., 19 May 2015. Web. 12 Oct. 2015.

“Stone Age Cave Painting.” Art Encyclopedia. Copyright Visual-arts-cork.com, n.d. Web. 1 Dec. 2015.

Weiss, Debra Cassens. “Courts Struggle to Sort out Meanings of Emoticons and Emoji.” ABA Journal. American Bar Association, 29 Oct. 2015. Web. 06 Nov. 2015.

Wroclawski, Daniel Wroclawski. “Emoji: Passing Fad or New Universal Language?” USA Today. Gannett Satellite Information Network, Inc., 25 Aug. 2014. Web. 27 Oct. 2015.

Context Links

Snapchat has taken emojis to another level

A study suggests that emojis might be difficult to interpret

A comprehensive Swiftkey study of global emoji usage and preferences