Digital America interviewed Schuyler Dragoo in April of 2025 on her work Simulacra Goose.

:::

Digital America: We see biases in AI systems because of their training data, algorithmic design, or human input, which leads to unfair or discriminatory outcomes in daily life or distorted outcomes in art. You mention these hidden structures and biases within AI’s attempts to replicate your movement and meaning. As you worked with AI software, did you notice any pattern in its errors or specific ways it misrepresented or distorted your gestures? Did you notice specific biases in how it responded and attempted to replicate your movements? If so, how did this bias shape your understanding of AI and its role as an observer and collaborator in meaning-making?

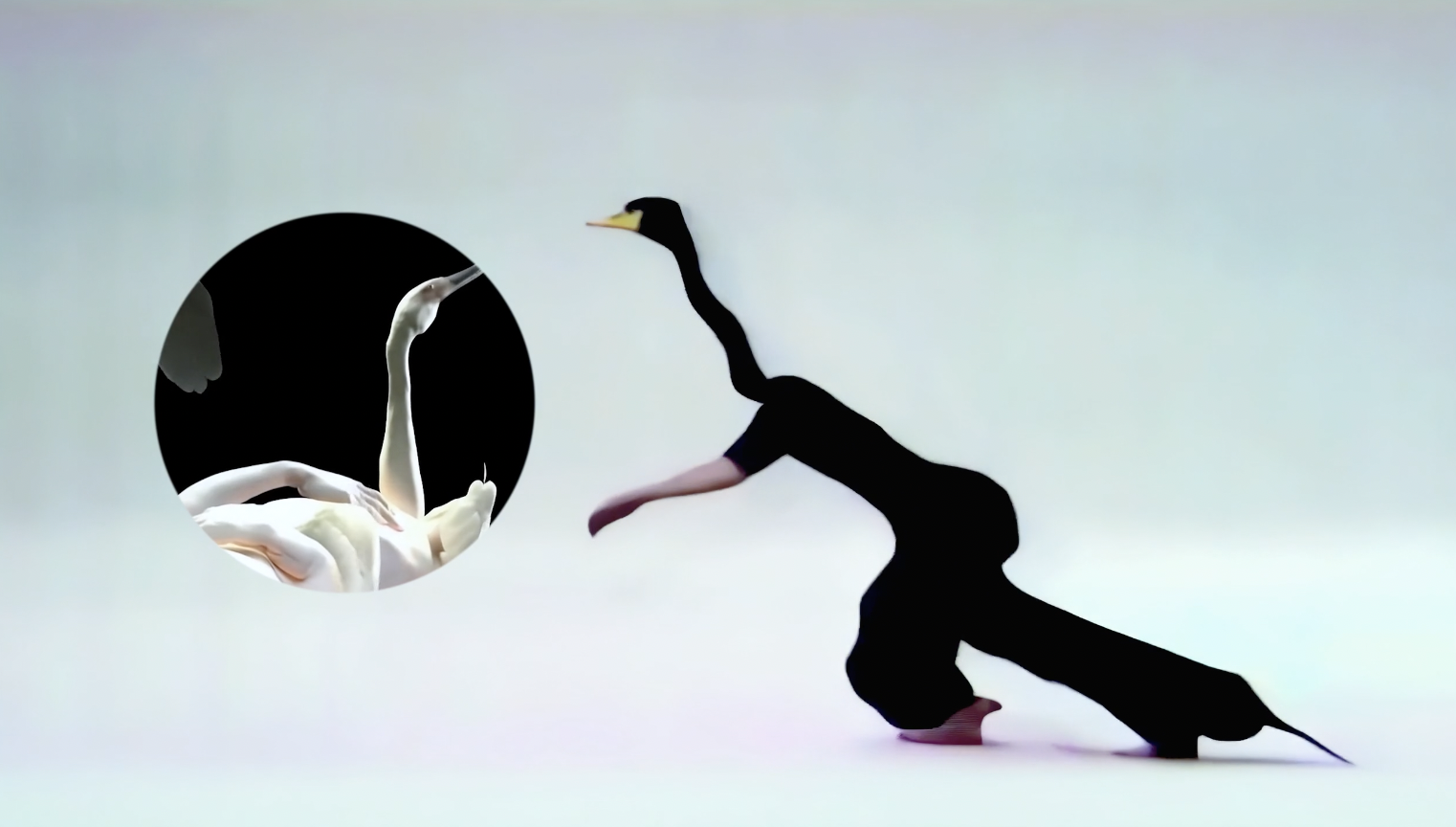

Schuyler Dragoo: While working on Simulacra Goose, I became increasingly aware of the ways AI systems distort gesture, misrecognize species, and flatten identity. These weren’t just technical glitches—they revealed deeper assumptions about bodies, perception, and meaning.

The video tool I used, Haiper, struggled to generate plausible human movement. Even without specific direction, it consistently had trouble “understanding” how humans move and continuing a movement. With the goose figures it created, it had similar issues. Joints bent backward, limbs moved in ways that ignored the logic of bones and muscles. It made me wonder: does the system understand motion at all, or just the illusion of it based on visual fragments?

That opened a broader question: if we ever turn to AI to reconstruct lost species, gestures, or environments, what will it miss? What kinds of knowing are possible only through being a body in the world? I began thinking about Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep and the differences between simulated memory and lived experience.

These distortions weren’t limited to movement. When I asked for an image of a goose, the AI often returned ducks—likely because ducks are more culturally familiar or frequently requested. But when I prompted it for goose-human hybrids, it rendered geese more accurately. It seemed to engage more carefully when it couldn’t rely on common visual shortcuts—though even then, it defaulted to familiar tropes like centaur-style combinations, drawing from mythology or pop culture instead of anatomy or nuance.

In the audio tool Suno, similar patterns emerged. When I asked for goose honks, it produced melodic, twittery sounds—more songbird than goose. It assumed I wanted something pleasant or human-adjacent. That raised new questions: Who is this tool designed for? What kind of listener does it think I am?

Across movement, sound, and visuals, the system often returned to a narrow set of defaults—thin, light-skinned, hairless, and gender-ambiguous or male-coded bodies. As a white performer, I hadn’t initially considered how race might shape my outputs, but in hindsight, I noticed the system never varied my skin tone. It also preserved my red hair—a detail that made me wonder if AI privileges surface-level visual data over cultural and social meaning. Is it simply replicating what it sees without understanding what those features signify?

While my work doesn’t directly center race, I recognize its importance in these conversations and approach it with humility—knowing I’m not the one to lead that dialogue, but remaining mindful of how these systems can reinforce structural erasure.

In Simulacra Goose, mimicry became a way of asking: What does the system think a goose is? A body? A listener? And what disappears when machines are trained to anticipate what we want, instead of actually listening?

DigA: You describe AI as a collaborator rather than just a tool, suggesting that its failures and misinterpretations generate new creative possibilities. I noticed the scene at minute 2:25 was cut short, and the white figures seemed misconfigured. Was this purposeful or a mistake made by AI you included in your piece? Can you share a specific moment in Simulacra Goose where AI’s ‘mistake’ led to something unexpected or meaningful? In that moment, did you feel like you were still in control of the piece, or did AI’s response push the work in a direction you hadn’t anticipated?

SD: The misconfigured white figures in the film were the result of an AI error. I chose to keep that glitch visible—I was interested in what it revealed about the system’s inability to render in-between forms. The clip is short because the software I used had a hard limit on video length at the time. I played with that constraint by slowing footage down and creatively editing around it.

There were several moments in Simulacra Goose where the AI produced something I hadn’t anticipated. One that stands out is a sequence of geese dancing on rainbow-colored backgrounds. My initial vision leaned more surreal than absurd—but those scenes felt so strange and over-the-top that I decided to keep them. I’m a playful person, and while the project explores serious questions, it’s still a piece about geese—there’s room for humor in the absurd.

That kind of unexpected input made the AI feel less like a tool and more like a collaborator—one that sometimes misunderstood me in generative ways. I still shaped the work and made all final choices, but there were real moments where the system nudged the piece in a direction I wouldn’t have pursued on my own. Letting go of complete control became part of the process.

DigA: Your work spans painting, sculpture, writing, and video, with AI playing a central role in many pieces. I noticed that in some works, you create collaborations with AI and your sketches, while other times, you leave sketches on their own with no collaboration. How do you determine which medium best serves a concept, particularly when exploring AI’s influence on movement and embodiment? Has AI ever pushed a piece into an unexpected medium or altered your approach to material choices?

SD: I think of AI as both a medium and a kind of collaborator—not in the human sense, but in the way it brings its own internal logic, aesthetic tendencies, and sometimes surprising detours. When I choose to use AI in a piece, it’s deliberate. The work is usually exploring technology, embodiment, or systems of perception—and AI’s presence can help deepen those themes. In other cases, using AI would feel like a distraction: something novel, but ultimately unnecessary. Like any collaborator, its value depends on context.

Sometimes, my medium choices are also shaped by practicality. Working digitally allows me to reduce material waste, create across locations, and experiment with transformation and motion. My sketches sometimes stand alone, and other times become inputs for AI—feeding into image generation, video sequences, or sound design.

So far, AI hasn’t directly shaped my physical material choices—I haven’t picked a medium because of a machine suggestion—but conceptually, it’s pushed me. It helps me imagine forms or movements I wouldn’t have conceived on my own. For now, it’s more of a partner in rhythm and sequence than in texture or tactility. That said, I’m curious about how it might influence future material experiments—through generative fabrication tools, text-to-material systems, or even surfacing unfamiliar processes I haven’t yet encountered.

DigA: In Simulacra Goose, you describe AI as a “mirror, intruder, and uninvited guest,” noting that the piece is “not really about geese” but rather a meditation on mistranslation, mimicry, and the limits of creative expression. Can you elaborate on the underlying metaphor driving the work and how the interplay between human, nonhuman, and AI agents complicates our understanding of perception and meaning-making? In that context, did you observe notable differences between AI’s interpretation of the human form and our own self-perception, such as the recurring tall, white abstract figure in the film, and what might that say about how AI sees (or fails to see) the body?

SD: In Simulacra Goose, mimicry is both method and metaphor. A goose moves—I mimic. I ask a machine to mimic me mimicking a goose. It’s a recursive loop of gestures that are never quite accurate, but still reaching. The piece isn’t really about geese—it’s about mistranslation, misalignment, and what emerges in the slippage.

I think of mimicry as an imperfect kind of empathy—an effort to relate without erasing difference. It doesn’t guarantee understanding, but it generates movement. As someone who is neurodivergent, I often feel misread by systems not designed for the way I think or move. Asking AI to mimic me became a way of watching that misreading play out, almost theatrically—through distortion, misunderstanding, and surprise.

AI in this piece isn’t just a tool. It’s a mirror, an intruder, and an uninvited guest. It reflects back patterns shaped by human training—but not always faithfully. The tall, pale, abstract figures that appear weren’t planned. They’re misrendered bodies—vaguely human but anatomically implausible. They weren’t symbolic, exactly—they were symptomatic: artifacts of how the AI tries to fill gaps in its training by falling back on what it’s seen the most.

These figures became a metaphor for how AI “sees”: not through embodiment, but through pattern. It doesn’t feel movement—it assembles it. It doesn’t perceive a body from within—it reconstructs one from fragments. That difference—between embodied self-perception and algorithmic output—complicates how meaning is made. The AI isn’t really seeing me. It’s simulating something it thinks resembles “human,” stitched from statistics.

But I didn’t erase those errors. I let them live in the work. Like the rainbow geese or warped gestures, they weren’t what I asked for—but they told me something anyway. Simulacra Goose is not a work about precision. It’s about the awkward collaboration between beings that don’t share perception. In that sense, the machine becomes part of the mimicry loop—not just reflecting, but participating in the misunderstanding itself.

DigA: Are you working on anything at the moment?

SD: I’ve been working on my thesis and completely forgot. As to current projects, I’m beginning preliminary work on a piece exploring neurodivergent perspectives, community, and collaboration. I’ve been talking with a few friends who work in other disciplines/ mediums about what collaborations could look like. I’m not quite sure what form it will take yet as I’m still in the very early conceptual stages. That being said, if any other neurodivergent artists are reading this who might like to collaborate, please reach out! I’m in the Boston area, but absolutely willing to consider collaborating remotely.

:::

Check out Schuyler Dragoo’s work Simulacra Goose.

:::