Ziyi Zhang’s Family Photo Album explores the relationship—and tensions—between cultures and personal art practice. Family Photo Album allows the viewer to explore the multi-dimensional stages of Ziyi’s life through a unique, interactive digital exhibition. In her writing, she refers to her “bestie” as the main protagonist in the story of the work. I interpret “bestie” as an exploratory characterization and extension of Zhang’s identity—as her own companion.

The exhibition begins with the viewer in the “waiting room,” a space in which they are welcomed with an introduction to bestie’s moral dilemma of betraying her gift of art. I find it interesting how while she introduces her art, she simultaneously admits she has abandoned it. Family Photo Album seems to be her goodbye tribute to something that has once granted her invigoration and purpose, but at some point, had to be put to rest. This notion speaks to how sometimes while we can walk away from the passions that consume us the most, we can still honor them.

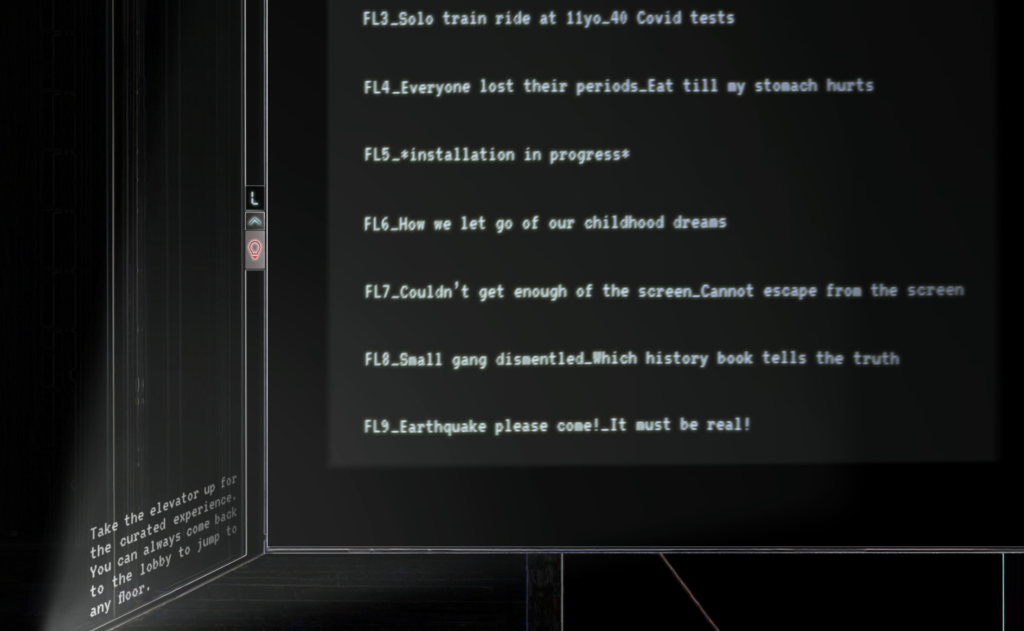

The waiting room of the exhibition lists each chapter of her life holographically displayed in front of an elevator. Each floor number features a title of what the viewer is about to experience, or the chapter they are about to enter. I find the “elevator” to be a manifestation of time passage and figurative teleportation, as the viewer can interact with her narratives chronologically or in any order they wish. Bestie extends her experimental production style by featuring a magnifying glass tool along with artifact pieces on the floor, allowing viewers to discover more of her narrative mystery in more detail. She honors herself as her own friend and memorializes elements of her life—whether that is a journal entry, a self-made illustrated video, or a photograph.

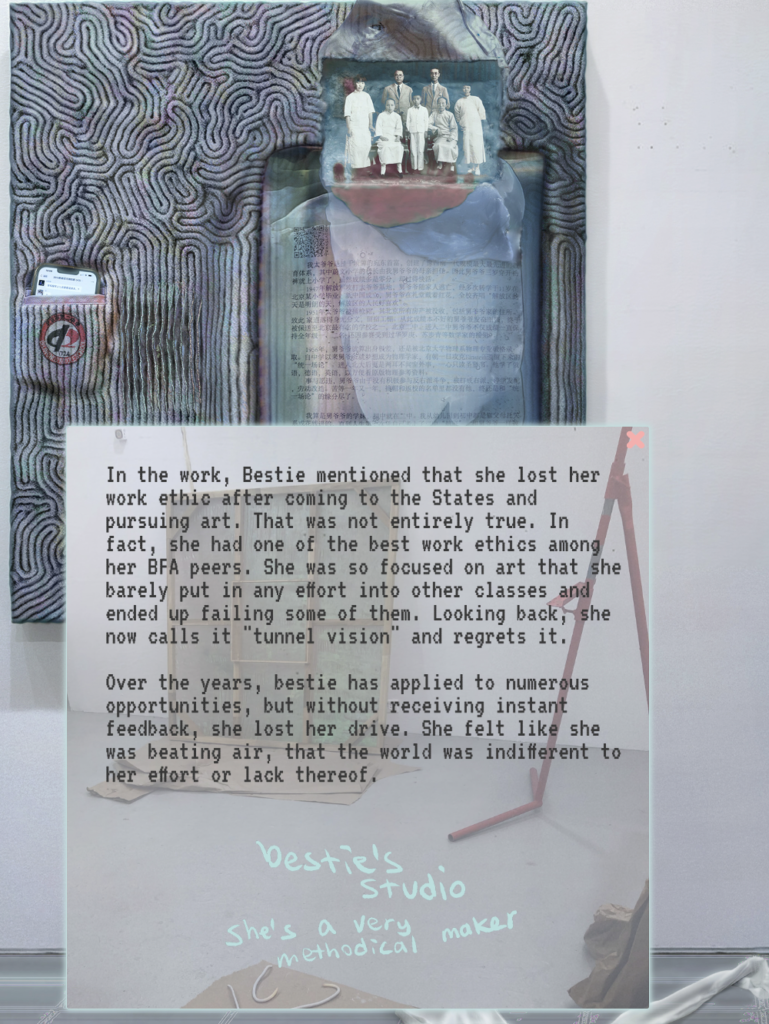

In her journal entries, Zhang writes in the first person, which communicates to the viewer that she’s narrating her own life. However, within the artifacts, she switches to the third person under the identity of “bestie.” She chooses not to capitalize bestie’s name. Perhaps she is resistant to the endowment and legitimacy of her own identity, therefore we may suggest she views the “self” as a general concept in the works of development. Furthermore, bestie is a casual and shorthand modern lingo for “best friend.” I interpret she uses bestie, tokenizing her her friendship with herself, while extending her ego outside of herself. In doing so, she also creates critical distance in revealing such intimate parts of her and her family’s lives. She constructs this identity extension as someone to care for, nurture, and tend to, just as one would do for their best friend.

Through dissecting the way she narrates her life, I gather that Zhang is under the characterization of bestie. In the introduction of the exhibition, she writes, “My bestie abandoned art because the art world disappointed her[…] She spent years making works for a series called the Family Photo Album (FPA) but never had a chance to exhibit it, so I decided to curate a show for it.” In Level 6, which is named, “How we let go of Our Childhood Dreams,” she explains how “bestie has applied to numerous opportunities, but without receiving instant feedback, she lost her drive. She felt like she was beating air, that the world was indifferent to her effort or lack thereof.” Zhang explains how she had to resort to independently showcasing her own project (FPA), which is the same exhibition we are currently experiencing. Her decision to independently curate this show suggests that she is bestie, and bestie is her.

Furthermore, the challenges of getting her art showcased connects to her opening up about her unhealthy coping mechanisms, as she explains in her journal entries. In Level 7, “Couldn’t Get Enough of The Screen,” she writes in the first person, explaining how “Eventually I’m not watching anything for enjoyment but all lost and surrender into an intoxicating binge,” when describing her unhealthy relationship with technology. Beneath this personal narrative, there is another text artifact, in which switches to the 3rd person: “When bestie falls into a screen watching binge hole, people cannot reach her for days. Then one day she will text her friends, ‘sorry I’m back’, and act as if nothing happened.” Especially in her vulnerable entrees, I notice she resorts to bestie, taking a step back into this critical distance of her identity, and playing with the subjectivity of her own truth.

I applaud bestie’s candid and vulnerable expression. She shares stories of her father, grandfather, and great-grandfather navigating poverty and hardships throughout the rise of Maoist China and the rise of Communism. I was moved by her storytelling abilities as she described her family member’s originally affluent and sophisticated socio-economic class to being struck down by China’s anti-rightist propaganda and its suppression of intellectualism and meritocracy. Right beside her family’s stories, she reveals issues with anxiety, alcohol use, technology addictions, and her eating disorder as byproducts of society’s overwhelming digitization. She highlights these dichotomies in her scrapbook-style art (embedding photographs from her grandparents in the 1950s People’s Republic of China right beside her technological indulgences of recent food delivery orders and YouTube binges), which I find to resonate with her intersecting identities, and their separate influences on her wellbeing.

Through the process of sharing these stories, I noticed bestie questions her own understanding of truthiness and storytelling production. She challenges how she perceives her truths and how she interprets them herself: Her personal narratives are true to her, but do they ring true to the actual historical events? Do they ring true to how her family members perceive them to be? Under propaganda, censorship destructs the truth. What elements do we deem trustworthy in the midst of power and control? She unpacks these questions throughout her chapters, inviting me to question my own stories passed down from my family, and how I interpret these truths.

While one may not face the turmoil that their ancestors did, one may still feel trapped in society’s highly digitized and consumerist nature. One may feel censored to express their own challenges, and that their emotions are not valid relative to those who have endured more palpable suffering in the past. And within this vulnerable dilemma, one might sever their monolithic identity, (like Zhang does with this manifestation of bestie). Ultimately, I was fascinated by her ability to examine herself in an out–of–body experience way. The choice of creating a critical distance between the artist and this extended identity is relevant to our human experience. FPA has shifted my perspective on how I perceive myself as a dynamic and transformative being, and how we can speak to ourselves as one would do for their “bestie”.

:::

Check out Ziyi Zhang’s Family Photo Album.

Check out Ziyi Zhang’s Q+A.

:::

Aylin is a Sophomore at the University of Richmond, majoring in Psychology and minoring in Rhetoric and Communications. She enjoys exercise, traveling, visual arts, writing, and listening to music. She is also a middle-distance runner on the Track and Field team.