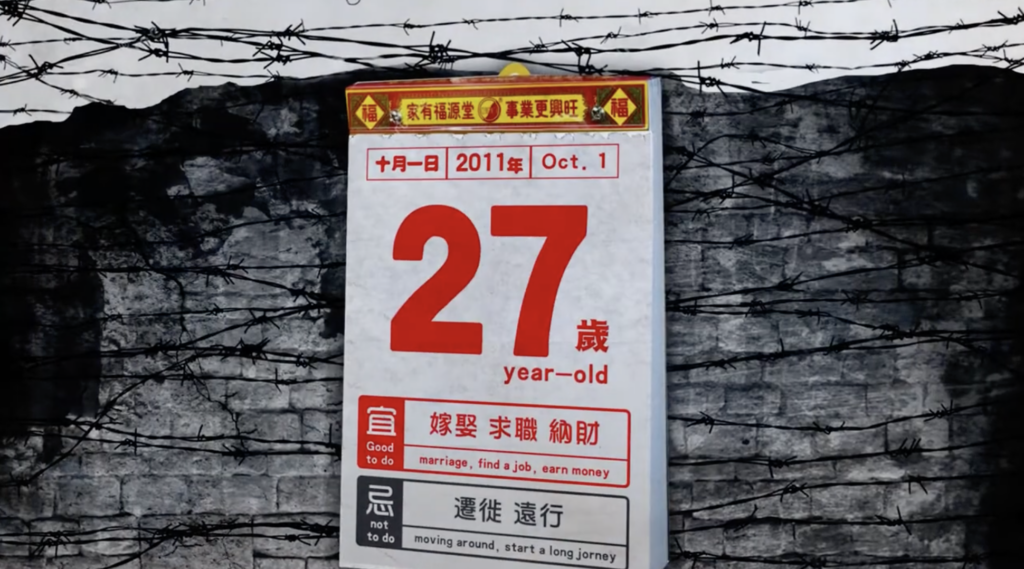

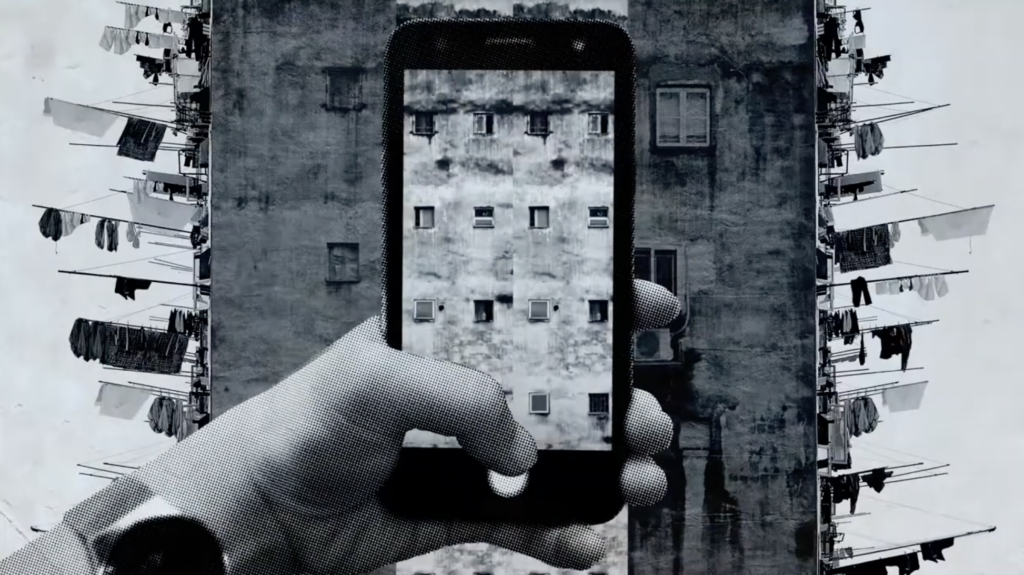

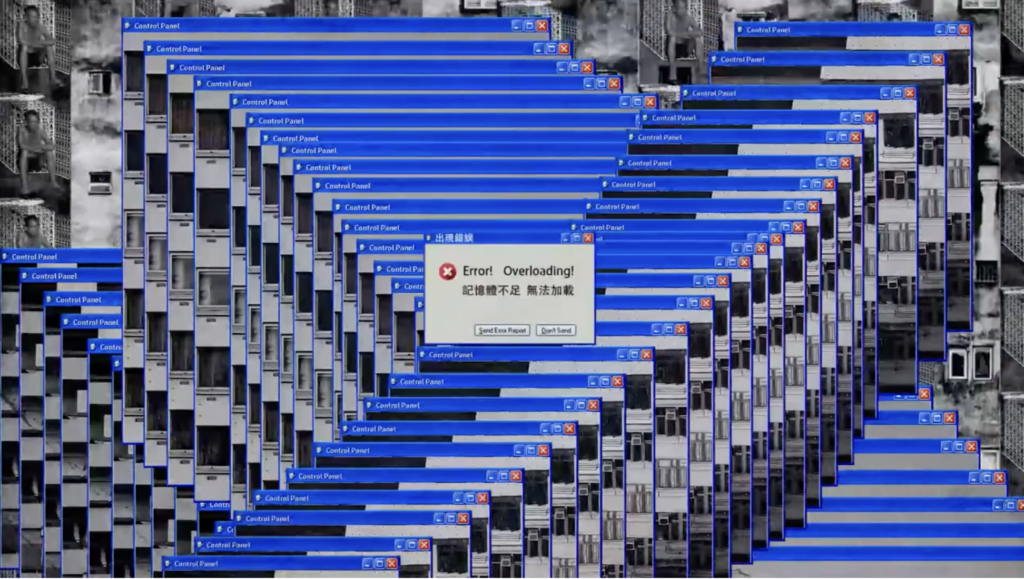

Crowded Dreams (2019) and The Manipulation of Life (2020) are animated collage pieces created by artist Ai-Chun Huang that immediately transport the audience into curated surreal landscapes. Using a variety of layered materials and set to a rhythm that sounds like seconds ticking away on a clock, Crowded Dreams (2019) journeys through an industrial dreamworld that amplifies the pressures of modern life. We are taken through this black-and-white landscape and shown innumerable high-rise buildings and apartment windows, each one representing an individual life. We are greeted by birds sitting atop barbed wire, calendar pages flying away, each with a different age and milestone attached, and roads where each lane symbolizes a decade. We are faced with technological motifs such as a phone filming one of the apartment buildings and error messages crowding the screen that says “Error! Overloading!”. At the end of this daunting journey, two building walls close in on the silhouette of a girl, and one instance of color appears. A vibrant blue ocean rises above this stark gray wall, and a hand reaches out of the water to grab a red balloon. But the hand sinks into the water, and the red balloon floats away.

The Manipulation of Life (2020) animation takes on a slightly different tone however, using more color in its frames, exploring more images of nature and using synthetic, emotional music. The most prominent natural image is that of a mountain. This mountain is seen through a window restrained by barbed wire and later tied up in red string. The most striking frame of this animation is the image of the mountain inside of a watch face, juxtaposed with staggering human silhouettes that are connected by a red string. The hands of the watch move rapidly forward. We follow the red string with the silhouettes as they walk up a loop of endless stairs, down the side of a building as one of the bodies falls, and through faceless busts of all ages

Both animations struck a chord with me emotionally. As a young woman in the internet age trying to find her “purpose” in life, whether that be found in a law degree, a new city, or something still unknown, Crowded Dreams (2019) captured the overwhelming anxiety of entering adulthood in the digital era. Her frame of the milestone calendar pages flying away was an excellent representation of the societal stress on young people to achieve different goals by a certain age, especially women who are typically pressured to fit domestic roles, hence the writing “have a baby, own a family”. I understand the feeling of societal pressure Ai-Chun Huang portrays since it has always been assumed by my family members that I would have children, without even asking if I wanted children. I do not blame them for thinking this way since they mean no harm, but it shows me that women are viewed as mothers first and foremost.

To me, the calendar is not just a symbol of societal pressures but a visual representation of my fleeting days wasted on the internet. Because of our reliance on technology, my time in the classroom is spent on the computer, my time studying is spent researching on the internet, and the way I have learned to relax is by scrolling online. A part of me worries that I’m wasting my youth on the internet, not just because of school, but because constantly watching other’s lives makes me wish I was somewhere else, doing something else, continually having my mind stuck in this digital space. Being connected to my peers around the world exacerbates the milestone pressures that Ai-Chun Huang portrays since I am constantly exposed to 20-year-old CEOs and 16-year-old supermodels, people who have achieved more in less time.

This same feeling is evoked when the Error! Messages cover the frame, a representation of the information overload and overwhelming nature of the internet. This resonates with me and many others from my generation who have grown up on the internet. Human beings now have access to an innumerable amount of information that we were never met with before, and the knowledge that we gain is overwhelming. I’ve had access to the internet starting at age seven, and being able to read about every horrible thing has been responsible for a lot of my anxieties, as I spent many nights lying awake, dwelling on the threats of climate change and gun violence. It was nights like those that I felt my brain was crowded with Overloading! screens.

Lastly, I was struck by the final frame of the singular red balloon flying away as the hand sank underwater. To me, the balloon, a bright red object in contrast with a drab, gray city, represented the letting go of one’s dreams to pursue society’s ideas of success. It reminded me of my decision to pursue a career in law instead of becoming the artist my younger self dreamed of. Looking ahead, I always saw myself as a film director, a fashion designer, or a painter without a single doubt. However, as notions of these careers sank into the back of my mind and the overwhelming desire to be successful for my family persisted, I pushed these thoughts away. I tell myself, “Those careers are better as hobbies anyways,” and “You would get sick of it if it were your job,” but deep down, I know what I want. The outstretched arm sinks into the sea of crowded dreams that cease to exist.

All of these feelings go hand in hand, feeding off of one another. Spending time on the internet “overloads” my ideas about what I should be doing at my age, telling me that I should have accomplished more by now. The pressure then builds up, paralyzing me and causing me to do nothing except scroll, and I see my life passing by like the torn-away calendar days. Ai-Chun Huang masterfully illustrates these complexities and how these aspects of society and the internet intersect.

The Manipulation of Life (2020) is a turning point, however, as I interpret it as a tribute to our interconnectedness not only as people, but with nature too. I understood the red string to illustrate how we have all been connected in our humanity since the beginning of time. Though they say the internet connects us, we have all been part of a bigger whole long before then. The red string ties itself to the hands of what seems like God and Adam, signaling the start of human connection. It travels through the passage of time represented in the watch face, even into the relentless modern era where each silhouette walks aimlessly up an endless loop of stairs. I also felt that The Manipulation of Life (2020) represented our interconnectedness with nature through the image of a human hand pouring out a vase to create an ocean and human tears falling into the body of water. Though it is a celebration, the piece warns us about the convergence of the industrial and the natural. The prominent symbol of the mountain is superimposed by layers of barbed wire, and then blocked by swiftly emerging high-rises. This piece reminds me that as a whole, we have the power to manipulate the quality of life for ourselves in how we interact with nature and each other. Though the digital age often causes me to feel heavy pressures and isolation, I am reminded through this red string that we are all experiencing this same world, all experiencing these same emotions.

Though Ai-Chun Huang’s pieces, Crowded Dreams (2019) and The Manipulation of Life (2020), do not shy away from the distressing nature of modern life, she reminds us that we are not alone, even if it is simply by being human.

:::

Check out Ai-Chun Huang’s work Crowded Dreams and The Manipulation of Life.

:::

Olivia George, Marketing and Communications

Olivia is a current sophomore at the University of Richmond, originally from Baltimore, Maryland. She is majoring in Politics, Philosophy, Economics, and Law and minoring in Latin American and Iberian Studies. Along with Digital America, she is involved with the school’s radio station, WDCE, Tri-Delta, and works as a Modlin Arts Student Ambassador.