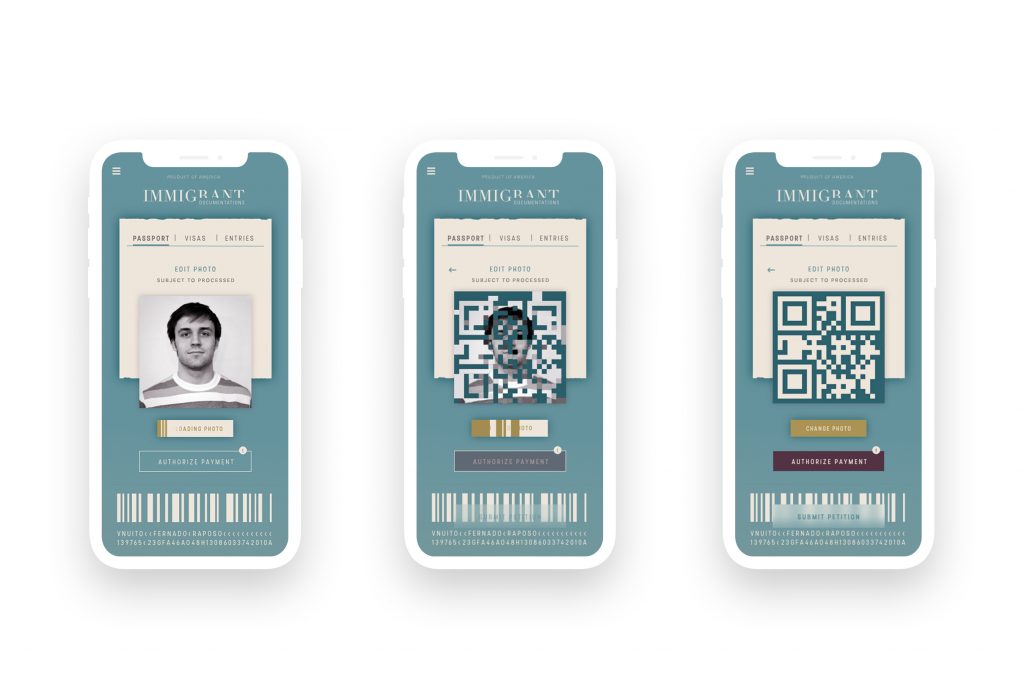

Since Digital America published Dao’s Immigrant Documentation (2018) four years ago, the US has continued use people fleeing violence and poverty as political pawns. Dao’s piece is unfortunately still timely as the red tape perpetuates dehumanization of immigrants, which is why we chose to resurface the piece. Most of our government business (like immigration and voting) is still done in person, with physical paperwork, despite the fact that many other important parts of our lives are now conducted online, from paying bills to storing SSNs in encrypted apps. Immigrant Documentation (2018) imagines a world in which more of the purposefully confusing immigration process incorporates the technology we use for everything else while questioning the problem and the digital solution.

:::

Digital America: You have a strong background in user interface design. Design and art, while seemingly similar, are often split into very different creative camps. How do you blend these two creative endeavors? How do you work with the tension between art and design?

Linh Dao: Art lends me the perspective to consider the social and political contexts instead of the business context in which my project takes place, which design does not. It is significant as interaction design projects can be pushing boundaries with new and emerging technology. There should be a reason for my work to exist in the world, and when there isn’t a client involved, I need to find that reason for myself. It can be additive experimenting, but ultimately, I must be grounded in my vision; while my work can be at a gallery, they belong to the hand-held devices that fit within the palm of the audience.

DigA: How do you feel the digital serves your art in a way physical installations cannot?

LD: Digital installations allow me to escape the narrow confines of galleries and museums especially given how the Covid-19 pandemic has shut down these traditional venues. Even prior to the pandemic, these venues were not always accessible for BIPOC or people who are less privileged. I also found that digital art installations offer new opportunities for viewers to actively interact with the artwork and to experience unreal scale that would be impossible otherwise.

DigA: Digital America featured your piece Immigrant Documentation in Issue 12 (2018). A lot has happened over the past four years—most recently the busing of immigrants from the US border to northern states. How has your work changed during this time? If you went back and revisited this piece, would you change anything?

LD: I think the conversation surrounding migration has intensified as the political climate has gotten especially volatile leading to increased displacement around the globe. The idea that migration is an exception needs to be challenged because millions are fleeing from climate or other inhumane conditions in addition to the genuine search for better social or economic opportunities. The recent development of immigrants being taken to the north is another sign of migrant lives being discarded as mere inconveniences, or disruptions, instead of necessities as part of the ongoing transformation of our country. This change is so inherently reflective of what we are, yet we seem to be constantly at odds with how to embrace it. We call our country the land of immigrants, but we have been putting walls up, closing our land, blocking immigrants, and turning refugees away.

I’ve learned a lot over the last few years. I have changed my assumptions, some of which I didn’t know I have before, around this topic. The content and form of my work reflect this change. It’s important that I include the ugliness of the situation. There is a very real temptation to flatter and reassure that I am still trying to avoid with my work. Wires and barbs are obviously not attractive, but I’ve gotten around to wanting to include them.

What separates me from somebody on the other side of the wall is just some prints in my passport, and I am not sure if my education makes me more worthy of staying than the people who are less fortunate. It seems like we have a system of merit here in place to grant admission, but that is only part of the process. I don’t know what it would take for me to feel like I belong.

If I get to go back and change this piece, I would have liked to spend a larger, more substantial budget on interviewing a larger pool of potential users, and to implement accessibility features. There are still a lot of opportunities there, especially with the tracking system and the search tool. For example, how would somebody who has a physical limitation on their hands like to use the search function? Would they like to be able to speak into it, instead of typing? Should there be an auto-filled option for the search screen? More importantly, the underlying theme of the over-militarizing and commercializing of the immigration process and procedure was there, but I think they both can be executed better. I wanted to create a more efficient immigration application, but I couldn’t hide the ugly truths about how our current system treats immigrants. I wanted to highlight them instead. I could have done a better job at that.

DigA: What are you working on currently? Do you feel that you are exploring similar themes (bureaucracy, invisible humans) or media (app/UI) to Immigrant Documentation?

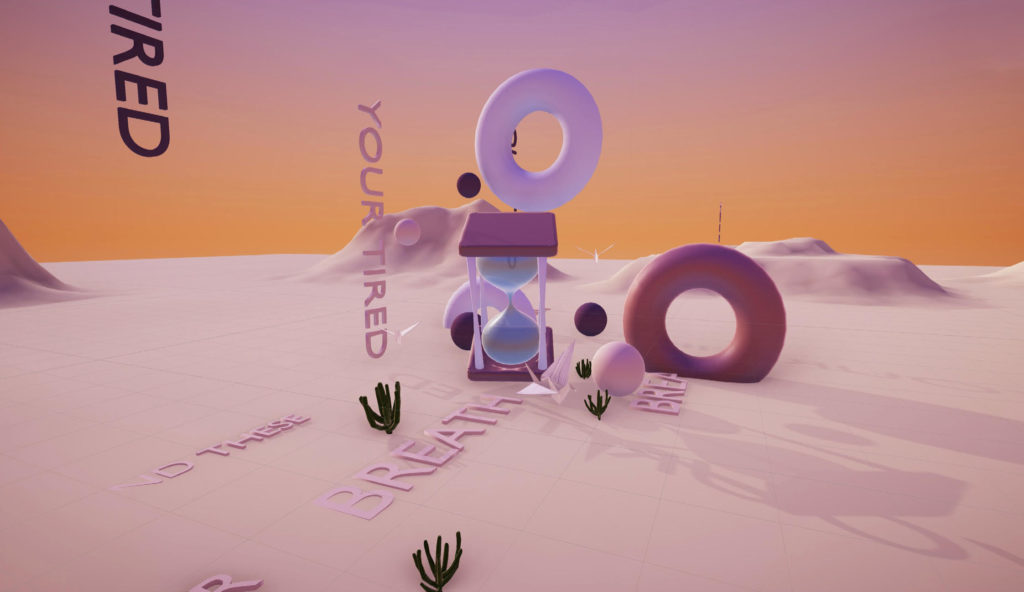

LD: I am working on an Extended Reality (XR) immersive experience depicting the journey of undocumented immigrants in a poetic spatiotemporal typographic landscape built on the words of the poem The New Colossus by American Poet Emma Lazarus. It is more abstract, but does share themes of over-militarizing and commercializing with my previous project, Immigrant Documentation.

DigA: You’re currently teaching at Cali Polytechnic, and last time Digital America talked to you in 2018, you were teaching at Monmouth University. How has being a professor influenced your artistic practice?

LD: I started my job at Cal Poly in the middle of the pandemic, so it was hard to find time to do research, especially because I don’t have the formal training in the more technical side of development. I had to learn to be patient with my practice. What I didn’t expect was how much I learned from my students, many of whom are second- and third-generation immigrants. Many students even look like me. I think that is an incredible privilege. Even though our backgrounds are not the same, I can understand some of their struggles. I am observing the world changing as I stand in the classroom. The question of whether and how my work is relevant to these young people and their world is very important to me.

:::

Check out Linh Dao’s Immigrant Documentation (2018), which we’re resurfacing from Issue 12, and her new piece, Decriminalizing Immigration (2022).

:::

Linh Dao is an interaction designer and educator whose creative and scholarly work explores the intersection between identity discourses and the development and implementation of creative and emerging technology. Her areas of focus include emigration, immigration, and migration, social and economic inequality, minority representation, and accessibility. Linh has exhibited both internationally and nationally, as well as published through IASDR and AIGA DEC. She has been awarded several design awards, including an Indigo Design award, Graphic Design USA awards, and a Creative Quarterly Design Category award. Her list of clients include American Cancer Society, Nonprofit New York, Rutgers’s National Institute for Early Education Research, New York Historic Districts Council, and San Francisco’s GLBT+ Historical Society Museum. She is currently an assistant professor of interaction design at California Polytechnic State University.