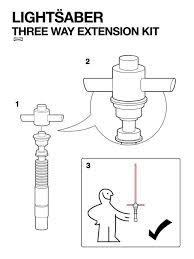

The teaser trailer for the seventh Star Wars movie hit the internet the day after Thanksgiving. As expected, it unleashed a torrent of commentary and speculation, but special attention was focused on the reveal of an unusual new lightsaber. In a scene lasting roughly six seconds, a cloaked figure activates an iconic lightsaber. Instead of just a single blade, two smaller shafts of energy also emerge from emitters on the sides. The result is a lightsaber that looks like a stereotypical real world sword with a crossguard. The internet exploded faster than the Death Star. Memes, earnest commentary pieces, wry Facebook posts, Ikea spoofs, and dismissive diatribes rapidly ensued. From the backlash, it appears that J.J. Abrams and company severely underestimated the number of internet users who are experts in lightsaber combat and medieval combat techniques. The lightsaber flap is reflective of how internet users parse and incorporate information from experiences widely outside their frame of reference, and then apply that knowledge to pronounce judgment on the inherently fictional.

Let’s get my qualifications out of the way first. I hold a master’s degree in history, so I know about old timey things. I have read some books on Renaissance swordplay and medieval combat, both for an undergraduate class and out of personal curiosity. I fenced for four years in college, mostly foil but dabbling in saber. (For the nonfencers, the foil is stabby and the saber is for slashing. Mostly.) While living in Taiwan, I took kendo lessons for six months, the Japanese martial discipline from which Star Wars lightsaber combat borrowed its initial cues. My kendo armor is currently on display in the corner of my room and if I turn most of the lights off and squint a little, it definitely looks like something from Star Wars. In addition to these physical world experiences, I am a 100th level paladin in World of Warcraft, I played through Knights of the Old Republic twice, and I’ve watched the original Star Wars trilogy, The Princess Bride, and Highlander more times than I can count. In all that’s close to five years of practical experience with swordplay as a sport, hundreds of hours worth of observing pop culture depictions of duels, an understanding of science fiction universes, and a reasonably accurate perception of historical swordfighting thanks to my training as a historian. The result? I have no idea how to fight with a lightsaber. Neither do you.

Why are people up in arms over a fictional weapon wielded by fictional characters? Popular culture, video games, film—they all have given use a false notion of simulated experience that we conflate with actual experience, an inaccurate point of reference that becomes a gestalt font of common wisdom. Let’s shuffle this sabacc deck into the real world. Ever watch an Olympic track event and see the eighth place finisher cross the lines ages after the first place runner? That person is still faster than you (unless you happen to be an Olympic runner, but I like my odds). Yet if asked you can still take part in a race, regardless of your skill. The last place finisher in any of the Olympic fencing events can still dismantle you in a duel with their weapon of choice with one hand behind their back—which happens to be the way European fencing works, but that’s beside the point. Even so, most people can pick up a sword and have at least a notion of how the whole dueling deal works. The incredible immensity of our virtual experiences through the medium of pop culture has generated familiarity with the even the most unusual circumstances—and has locked us into often rigid ideas of the way things should be because we overlay widely different notions from a range of cultural artifacts over different circumstances.

For the detractors of the crossguard lightsaber, the most common argument is that a user would seriously injure themselves using such a weapon. Where does this apparently obvious and common knowledge come from? Are most internet users versed in fighting with a blade? Or have they seen depictions of sword combat, and then mentally applied it to their own abilities, experience, and favorite hilariously painful YouTube videos without adding decades of practice and space wizard powers? Swordplay is one of the combat arts that we can no longer truly replicate, unless that underground death match tournament in 1994’s Ring of Steel actually exists. There are schools that purport to train in genuine old time swordsmanship, but they all lack the important part—the deadly reality of trying to murder another person while not getting murdered yourself. You and I are far, far removed from the Star Wars universe, but to conceptualize it, to put it into a frame of reference, we impose what we do know, what we have experienced, and what we personally can do. In an age of information, we want our fictional worlds to be deep, in some respects as deep as the real world. By giving popular culture ever increasing layers of reality, we impose the rules we expect of the real world in order to explain, to extrapolate, to make it “real” by forcing conformity to what we do understand. At times, it backfires horribly—witness the perplexed incredulity over ideas of trade negotiations in the prequel trilogy. By imbuing the fictional with the trappings of reality we expose the very real faults in our Star Wars.

To compound the problem, Star Wars has developed a body of literature that rivals several established academic disciplines, a series of works that compose facts within our fiction. Like an oroboros constantly devouring itself, the history of a fictional world like Star Wars is built upon the works of writers who were simply trying to tell a story, which is was incorporated into other works and then carefully cited as fictional fact. We have little way to parse the information we find online. To make a comparison to academia, the careful work of a lifetime from giant in a particular field holds equal weight online to the gleefully enthusiastic but thin thesis of a undergraduate, with little way to tell them apart. Star Wars has already tried to explain the apparent weakness of lightsabers in combat by inventing invulnerable metals but through lesser known media. We have the benefit of all the knowledge at our fingertips, but in the parlance of Star Wars, we have no Jedi Master to teach us. Eternal apprentices, guided by personal sentiment, we are able to ignore what we don’t like (midi-chlorians), become hobbled by what we didn’t bother reading about (Marvel’s 1977 to 1986 run of Star Wars comics), and sit confident in our abilities without ever being truly tested.

For my Trade Federation credits, the crossbars have been added so the lightsaber looks cooler, with an unusual new profile. It gives the creative team the chance to do something different in fight scenes from the previous films. It’s the same reason Darth Maul had tattoos, the same reason X-Wings have a racing stripe down the hull, the same reason C3-P0 has a sweet gold finish. Someone thought it looked good. It is someone else’ job to explain it, and our job to judge it.

References

http://starwars.wikia.com/wiki/Lightsaber

http://starwars.wikia.com/wiki/Midi-chlorian

http://www.starwars.com/databank/trade-federation