The world of popular gaming mirrors the development of Hollywood action films: grandiose attempts at virtuality, holograms, and 3-D fantasies, with non-stop violence, misogyny, and the overuse of traditional, linear narratives and tropes. Even game trailers are difficult to decipher from those of live-action cinema. Yet, as is always the case, on the peripheries exist games which eschew much of the aforementioned generalizations, and, which both reference the history and theory of game, while simultaneously subverting what game-play can be.

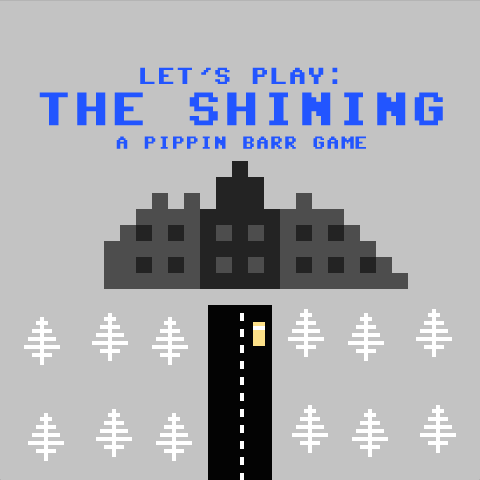

Pippin Barr’s latest release, Let’s Play: The Shining is a game version of Stanley Kubrick’s film The Shining (1980), based on Stephen King’s novel (1977). As with Kubrick’s interpretation of King’s much different tale, Barr prefers a less direct retelling of the film, by focusing on significant vignettes using a visual and sound aesthetic reminiscent of earlier Atari 2600 game console. Throughout the game, the user is assigned different roles: from the mentally deteriorating Jack Torrence, to his wife, Wendy, and their son Danny. The game controls are simple: space bar and arrow keys.

The game begins as the film does –with us driving Jack’s car across a beautiful landscape, in bird’s eye view, while a version of electronic pioneer, Wendy Carlos and Rachel Elkind’s powerful opening theme accompanies, dark and thunderous even in its midi-like incarnation. Very quickly, the user must realize that this is unlike a typical game, for we are unable to crash the car, or go the wrong way –instead, with arrow keys we simply make our way around turns until we reach the destination –the Overlook Hotel. This seemingly banal game play makes up other moments too: from Jack’s throwing of a tennis ball (which we are then supposed to catch) as he continues to grapple with writer’s block, to Wendy and Danny’s play in the hedge maze. In all instances, the rules and goals are few and simple –with no bells, whistles or explosions –but this all acts as a comfortable set up for the game to come.

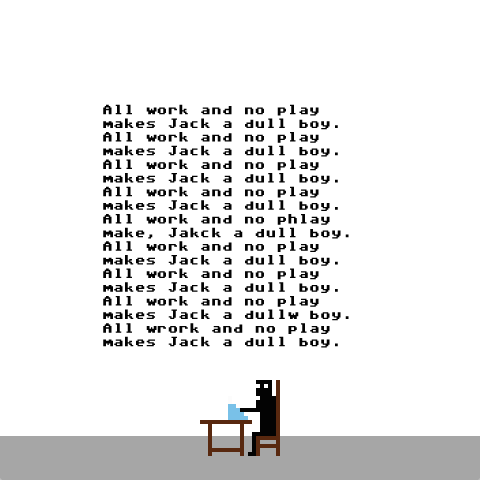

The game begins to turn as Jack sits at his typewriter, and together we type:

All work and no play

makes Jack a dull boy.

All work and no play

makes Jack a dull boy.

All work and no play

makes Jack a dull boy.

All work and no play

makes Jack a dull boy.

It is from this moment on that we are, as players, made more aware of the tactile aspects of the game and Jack’s turn to madness. Barr’s genius lay in his ability to take the simple game controls of space bar and arrow keys and enhance the user’s virtual experience while also acknowledging the medium, or system that makes up the entire process of play, rather than the backgrounding that occurs with a more realistic 3-D render.

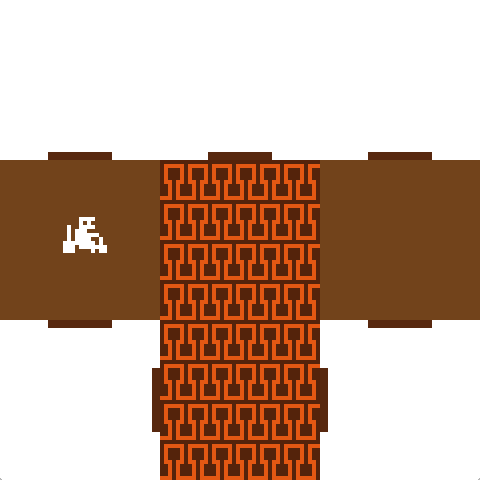

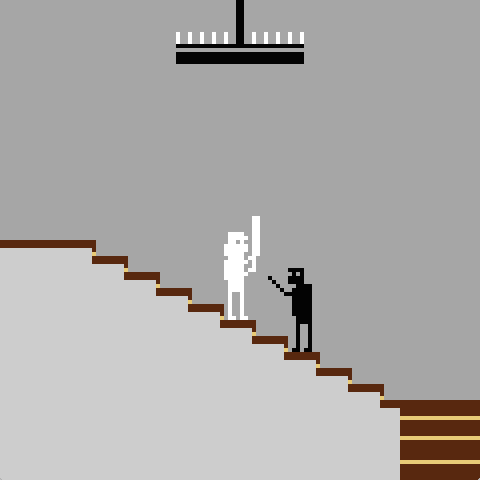

In another wonderful moment, we are Wendy who has just come to realize the extent of Jack’s mental breakdown, and must back away, up a staircase, while swinging a bat at Jack, as he threateningly gestures. The stage is “passed” when we bash his head and he is knocked out. However, the most powerful gameplay is left for one of the most famous scenes in horror film history. We are now Jack, who, with axe in hand, must break down the bathroom door, behind which Wendy hides. This requires the user to swing Jack’s axe by making a full rotation with arrow keys:

From the down position we then click left-arrow, and we then raise it up, and finally, bring the axe crashing down into the door –right. Repeat: down, left, up, right, crash! Down, left, up, right, crash! Our fingers begin to become more graceful in this axe wielding, arrow-keyed process. Until finally we stick our head in the hole, and are left only to imagine that famous phrase, “Here’s Johnny!”

It is an absolute achievement to induce in the user a sense of physical connection to a game without emphasizing visual reality. No, instead, Let’s Play: The Shining is a more self-reflexive practice of play and human-machine interaction. One in which, the keyboard-as-appendage is both an entry into a fantasy and a tool for our control of that same world. The user is both playing and playing with the idea of a game –completely self-aware. Interpretations of Kubrick’s film vary, and they include the possibility that the Torrance’s themselves, or at least Jack, have always been there, fated to repeat a cycle of terror. Unbeknownst to them supernatural forces potentially code their roles for them, like a game, playing them against each other. And yet, Wendy and Danny escape the fate of the murdered wife and twins –perhaps breaking the rules or rewriting them. Barr gives the user multiple roles in his remediation of The Shining, itself an abstraction of the novel, and this time, the viewer is also actively Jack, Wendy, or Danny. We already know the fate of Jack, and maybe now, we are reminded of our own role in the entire process of codes, systems, loops, and game play.

Barr, also the creator of a brilliant game version of the process of waiting in line to participate in Marina Abramovic’s The Artist is Present performance at the Museum of Modern Art, creates the kind of playful, thought provoking work that gives one pause and hope for the future of game play and computer-based art in general.

Resources

Play the game here.