Introduction

It wasn’t until the advent of Tinder, the popular casual dating app that launched in 2013, that I could quickly explain Grindr, launched in 2009, and all its clones (Hornet, Scruff, Growler, Jack’d, A4A, Radar) to a non-queer audience. Grindr is a cellular digital space for men with same sex desires that centers on a user’s geographic location. The app is used for networking, cruising, conversing, or organizing, and some users refer to it as a “bathhouse for your pocket.” Over a summer, I had been working to capture the human forms of anonymous Grindr users through informal portraits. Not only has this project allowed me to delve deeper into an analysis of individuals’ self-presentation in digital space, but also, the time I have to compose each portrait is mediated by time—the time each body is ‘online’ in my proximity. Audiences, academics, and curators did not understand the space, community, activity, or bodies that I was referencing in the project (despite the over four million users worldwide). Eventually, I was able to garner some attention for the series as well as interest in its theoretical underpinnings by working to illuminate the manifestation of racial preference and selection by the app’s users.

Grindr Portrait Series

I had recently graduated from university with a BA in Studio Art and was spending the summer relaxing before heading off to graduate school. I had focused on sculpture through undergrad but assumed that some might expect me to have more skills based upon my credentials. I thought I could spend the summer sketching, drawing, and painting so that I would be better prepared for graduate art school. At the time, I believed the best painters’ work sought to better understand the human form. So, I followed their lead in my self-directed study of painting. I was a frequent Grindr user and noticed that the bodies splayed across my smartphone screen were perfectly proportioned by my phone’s screen in relation to my sketchbook and, later, canvas boards. I began to paint and accumulated dozens of tiled portraits. While I originally thought of these images as individual attempts to perfect my craft, a mentor advised I treat them as a unified creative project.

As the project developed, I began to notice various themes emerge across a veritable sea of profiles—for instance, Profiles Pics of Chests were looking for “Networking” or startling textual profiles with phrases like “Whites Only.” At the time, I was painting the first 100 portraits in Richmond, which has a strong historical past of racism, slavery, colonialism, and violence. Consequently, I became very disturbed by the recurrence of users looking for “White Only,” “Masculine Males Only,” or “No Trannies” as that language reproduced attitudes grounded in the misogynistic and the Jim Crow South. This led me to write a series of articles and opinion piece for GayRVA.com that examined, countered, and explored the politics of Grindr. I collected all of these portraits and texts into a single book—through Blurb—and published it in print and digital forms. My article about race received the most retweets and comments, presumably because it forced readers to react to the claim that our sexual desires, even in 2014, were mediated by white supremacy.

Race in Queer Spaces

The most apparent discrimination—both digitally and physically—arises around race. The issue of oppression reappearing in this digital community space is disturbing but, on reflection, not overly surprising because it is apparent in so much of the non-digital spaces for queers. Racism becomes interwoven with sexuality as the pre-digital queer theorist Foucault has explained through biopolitics, yet isn’t always addressed or acknowledged;[1] “the set of mechanisms through which the basic biological features of the human species became the object of a political strategy, of a general strategy of power, or, in other words…modern western societies took on board the fundamental biological fact that human beings are a species.”[2] There is a long standing critique of mainstream queer organizations like the Human Rights Campaign, National Gay & Lesbian Task Force, Gay Liberation Front, and Equality Virginia that focuses on their white washing of LGBT community’s struggle for ‘equality,’ vision for the future, and movement culture. This criticism focuses on the fact that many, if not most, queer organizations employ predominantly white passing individuals. Coincidently, many of their advertisements, outreach, and policy programs target, focus, or feature white folks. Critical engagement with our spaces, organizations, and behaviors remains paramount as Jose Estaban Munoz reminds us because “from shared critical dissatisfaction we arrive at collective potentiality” that leads to utopia (or at least its borders).[3] Groups like Southerns On New Ground or Gay Asian Pacific Islander Men of NY have arisen to create safer queer spaces, especially for men of color. They have worked to counter racist practices by more mainstream LGBT organizations, bars, community centers, and businesses that prioritize the white community.

Within digital spaces like Grindr, many users defend their particular sexual racial declarations as a preference versus a fetishization. Yet, many are unable to articulate how this preference was developed. I believe this ‘preference’ arises based upon our socialization by a media culture that privileges the stock image of the fit athletic white male as the standard by which all other human corporalities are examined and judged. It’s presumable that these online space would erase the systems of oppression that are so reliant on visual aesthetics but as D. Travers Scott states “the design and functioning of online technologies is far from immune to racism, sexism, homophobia, and other social ills.”[4] Many of my queer friends of color have relayed how these declarations of “White Only” make them feel uncomfortable and consequently leads to them leaving the space by deleting the app.

A counterpoint to Grindr, Jack’d actually displays a user’s messaging behavior when it comes to race through its ‘Insight’ feature. This feature publicly displays the demographic data regarding a user’s engagement with others through age, body size, scene, and ethnicity breakdowns. This data is a useful tool to check in on one’s own behavior and selection of sexual partners to see if there is a disproportionate selection of certain identities. Michael J. Faris, a digital rhetoric scholar, has written about his own racial assumptions and affects in digital spaces and the need to “interrogate ourselves and our own desires, until we can get to the point where we fuck based on what we want to do, and not on the type of body we want to do it with.”[5] I have noticed that Jack’d usually features more people of color then the mainstream apps like Grindr. Sadly, Jack’d doesn’t provide data around gender performance like masculine, feminine, or 3rd gender expressions.

Masculinity in Queer Spaces

A profile that typically displays “White Only” usually includes the next phrase of “Looking for Masc” or “No Fems.” This implies that effeminate men are not desirable and replicates many of the issues around homophobia, which sees queer men as lacking strong masculine attributes, features, or expressions.[6] This disapproval represents a manifestation of sexism, which sees the effeminate as weak and inferior. The constant repetition of the phrase creates a culture of policing that replicates gender constructs with a prioritizing of the masculine. This climate does not erase the negative associations of femininity or patriarchal systems of oppression that are linked to these gender constructs. Furthermore, it creates a hostile space for anyone who isn’t masculine or traditionally male bodied, like Trans* Men.

In Why Are Faggots So Afraid of Faggots, Mattilda Bernstein Sycamore outlines the recent revival of the cult of masculinity within gay culture as a result of intersections of capitalism, patriarchy, and time. The anthology maps the radical shift from a gay liberation politic to one of assimilation and how “it is surprising how the intoxicating visions of gay liberation have given way to an obsession with beauty myth consumer norms, mandatory masculinity, objectification without appreciation.”[7] This erosion of gay liberation mentalities becomes readily apparent after using Grindr for an extended period of time.

I am continually asked about my gender expression when starting up conversations on Grindr. This is a complicated question with an equally convoluted answer, particularly after reading works by Judith Butler like Gender Trouble, which establishes how gender is performative: “Gender is a kind of imitation for which there is no original; in fact, it is a kind of imitation that produces the very notion of the original.”[8] Understanding gender as a social construction allows us to see it as an expansive spectrum for which there are no definitive definitions or categorizations. Returning to the question of my gender expression, it becomes difficult for me to locate a definitive answer within the binary that the inquisitor desires or understands. I am fairly effeminate in my voice and mannerisms, yet I grew up on a farm. Consequently, I can perform very masculine tasks like changing tires, shooting a gun, using manual transmissions, gutting deer, driving a tractor, working with cattle, and etc. However, my physical gender expressions like voice and mannerisms quickly overshadow my gendered activities and knowledges. We are consequently policed about our performance of gender and reminded about the inferiority of the feminine by statements like “Masc ONLY.” These mirco-aggressions can become grating through their apparent repetitions in various profiles and conversations. Congruently, gender becomes the scale that validate, judge, and value conversations and relationships.

Faris reminds us, “Our society has fucked up our sexual desires so that we’re so fixated on other people’s bodies that we forget about what we actually want to do in bed (or in a car, in a park, in a porn booth, and so forth).”[9] As a community, how do we begin to understand and orient our desires and ourselves so that we do not replicate systems of oppression? How do we understand and conceptualize our understanding of gender and its relationship to sexuality? It will take many steps towards ending the violence and oppression. An easy first step can be to check the text of your own dating profile to ensure it doesn’t exclude or reinforce hierarchies.

Where do we go from here?

While Grindr does create yet another space where oppression is replicated, it does offer a new space for dreaming, community, connection, and desire that cannot or no longer exists in physical places. The earlier description of Grindr as the “bathhouse in your pocket” allows for further investigation of the space through a similar analysis developed for its more physical manifestation. Some critics attack the bathhouse for its hyper sexualization and commodification of desire yet others see it as a revolutionary space. Aaron Betsky remarks in Queer Spaces: Architecture & Same-Sex Desire that the bathhouse “was [a] space that many queers describe as giving them a sense of community, which was liberating them in a mist of stream from their physical constraints (164).” This statement builds upon his earlier declaration that “queer baths has established themselves as places of assignation and sometimes even community building” (162). I feel that some of the removed physical restrains revolved around racial preferences or gender expression along with internalized homophobia. The mist hid these attributes as it created cover for desire that required the tactile versus the aesthetic.

Grindr hardly creates a mist for community building as it relies upon the aesthetics; Its CEO, Joel Simkhai, remarked, “I’m very proud if Grindr has forced us to up our game. To brush our teeth. Comb our hair. Eat right. Go to the gym. Be a healthy person. Cut back on the smoking. Cut back on the bad things and look your best. We’re men. We visualize.”[10] His comment highlights the aesthetics structures that inform out desire and are reinforced by the interactive visuals of Grindr. Alongside these troubles, it does offer some potentials and purposes for queer political organizing. As a rural queer, I find it very helpful in connecting with others across a wide geographic expanse. Conversely, the bathhouse becomes a “public manifestations of such sexuality were both a respite from the abjection of homosexuality and a reformatting of that very abjection.”[11] Grindr is a public manifestation of queer sexuality—housed on our phones and Apple/Android App Markets—that reinterprets the notion of a bathhouse for a more digital and modern world. Grindr’s makers understand their public-ness and actively engage with it through its Grindr for Equality initiative.

Grindr for Equality attempts to steer their users towards political actions. Since the Romans, the bathhouses have been places for the discussion, strategizing, and debate of politics; granted, it is usually gender segregated and focused on men. Grindr states that this initiative focuses on connecting its 4 million users and “harness this huge global network to do some amazing work for GLBT equality and to advance the cause of our community worldwide. Simply put, let’s use Grindr to organize and fight for our rights.” This harnessing usually develops into geo-targeted messages that encourage users to participate in rallies, meetings, protests, or dialogues. Interestingly, Turkey recently censored and banned Grindr during their recent uprisings due to its ability to mobilize.[12] We can build upon this platform to bring together an assembly of queer folks to strategize, theorize, socialize, and instigate change.

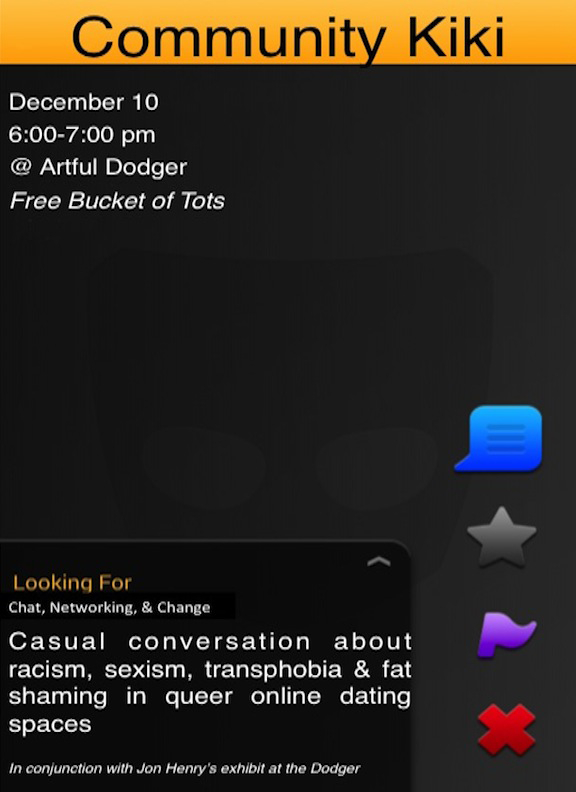

I wonder how we can tap into the space of Grindr to achieve our liberation. How can we transform the space into something queer where systems of oppression are minimized and removed? Theorist Judith Halberstam refers to “Queer space” as “the place-making practices within postmodernism in which queer people engage and it also describes the new understandings of space enabled by the production of queer counterpublics.”[13] I think I tapped into some of the counterpublics potentials of Grindr (and Adam4Adam) when I organized a Community Kiki in Harrisonburg, VA, which created a physical space with tater tots to discuss oppression in online dating apps, through Grindr ads. The conversation proved fruitful as it brought together a variety of individuals across spectrums of identification for a heartfelt conversation about the replication of oppression in the digital realm. For some, it reaffirmed and articulated their own struggles, thoughts, and theories about these spaces; for others, it engaged them in a new topic that provided frameworks, advice, and language for change.

Bathhouse in Your Pocket

The old Roman Bathhouses were the places of politics, business, and pleasure and it seems the digital bathhouses might serve similar purposes.[14] The Roman and modern queer bathhouses were slowly dismantled in part due to Christian sensibilities and the fear of sexual infection pandemics like AIDS. Like Grindr, Roman baths were places that highlighted the male form as users were usually segregated by gender and nude. The baths encouraged patrons to become physically fit as the complexes housed a palaestrae—gymnasium—alongwith exercise equipment as noted by one Roman citizen: “While the sporting types take exercise with dumb-bells, either working hard or pretending to do so, I hear groans; every time they release the breath they have been holding, I hear sibilant and jarring respiration.”[15] Grindr’s CEO Joel Simkhai would enjoy the fact that these baths encouraged citizens to ‘up their game’ in terms of cleanness and fitness as it provided a space ‘to brush our teeth. Comb our hair. Eat right. Go to the gym.”[16] More importantly, the baths provided a physical space for same-sex desire and sexual exploration.

The gay bathhouse began to appear in the US in the later 1950s as exclusive spaces to express, experiment, and engage in same-sex desire.[17] Previously and congruently, bathhouses like the YMCA were intended for heterosexuals yet appropriated for same-sex desire as exemplified in the Village People’s YMCA song.[18] However, by the late 1980s with the AIDS pandemic was in fully affect, the New York City Health Department to order the closure of all the city’s gay bathhouses. These measures stereotyped the bathhouse as centers of sexual depravity and risks to public health and safety, even though “there was never any evidence presented that going to bathhouses was a risk-factor for contracting AIDS.”[19] Before AIDS, going to a bathhouse was not only considered socially acceptable, but encouraged as a gathering place. A bathhouse offered a place where it is safe to be gay. The movement to secure civil rights for gays got help from meetings in bathhouses. Bathhouses have transformed many young gay lives by banishing shame and offering them an accepting community.[20]

I find that Grindr can become a place to explore identity and sexuality through temporary profiles and selfie free profiles. These digital identities can quickly be thrown away, edited, or transformed as one maps out their own desires, feelings, and politics.

I still continue to engage in long conversations with others around identity and social constructions, especially if another user is from another country. The activist Chris Bartlett remembers a similar mode of dialogue occurring in the bathhouse: “I know gay men who have described this lightness through stories of sitting in the bathhouse on each other’s beds and talking about their lives and politics.”[21] The social political uses of the gay bathhouse are further exemplified in the 1980 NYC election when the New St. Marks Bath collaborated with the League of Women Voters to conduct voter registration drives in their premise. [22] Grindr for Equality has also offered similar services. The increases in police raids, insurance, and operating costs led to the closure of most gay bathhouses. Those that still exist, endure as places for politics, education, and sex. Still, I find myself discussing politics or engaging in philosophical debates on Grindr. The most rewarding moments—besides the sex—appear through the community development that arises through Grindr like the nod at the straight bar, long lasting friendships, rallies, book clubs, and dance parties, which are arranged, coordinated, and executed through Grindr.

Conclusion

As our society evolves and incorporates digital culture more and more into our lives, I see the lines blurring between bodies, relationships, and technology. Already our mating rituals are changing as 25% of marriages result from online dating.[23] It was my Grindr portrait project that opened me to the tangential experience and potentials of these new online spaces. It also was a project that highlights the darker trajectories of online spaces through their replication of oppressions. Submerging ourselves in the electric pool of the bathhouse can titillate and produce political rewards, yet, we—like lifeguards—must keep a vigilant eye to ensure there are not catastrophes.

Context Links

Here’s a link to Grindr for Equality [link no longer accessible].

An article talking about whether or not bathhouses in 21st century San Francisco are feasible

A recent Wired cover story called “How Airbnb and Lyft Finally Got Americans to Trust Each Other”

:::

Jon Henry began xer artistic journey in the foothills of the Blue

Ridge Mountains. Henry graduated from Highland in 2008. After living

in Richmond, Irbid, and NYC, xe settled back into the Blue Ridge

Mountains to further develop xis practice as a Studio Art MFA

candidate at James Madison University. Xis work explore the

intersections of queer and southern identities through relational,

community, and socially engaged practices. Henry is currently

developing/curating/producing/creating/living in the Old Furnace

Artist Residency, which serves as an over arching entity for a variety

of xeir projects. Follow xar trajectory at: thejonhenry.com.