Eric Millikin is a conceptual activist new media artist based out of Detroit, Michigan, and Richmond, Virginia. Through his work, Milikin explores the intersections of advanced technology, American society, dark humor, and occult practices. In this Q+A, we speak with Millikin about his recent digital zine VIRONOMICON, as well as other works.

:::

DigA: The breadth of your work includes street-art. How does your approach differ when creating public street-art compared to public digital art on the internet?

Eric Millikin: Yeah, I often most often work in ways that are designed to reach as many people as possible. To me that’s sort of a basic question for every artist, “Who are you making artwork for?” If you’re just making it for yourself, that’s cool, no need to show anyone else. I’m making artwork for other people to experience, so I work in ways like public street art, public web sites, social media, digital printmaking, artists books and zines, mass media, video and audio files, many different ways that can be easily distributed and reach wide audiences and create and take part in larger conversations.

The strategies can sometimes be different between public physical objects in public spaces and artwork distributed digitally, but also strangely similar. Public street art you have to think about making something to withstand the elements and the passage of time; internet art you also have to think about whether you’re using some technology that browsers won’t support in a few years, or how long you’re going to keep that server up and running, or whether you’ve got a back up saved. Street art you might think about whether your work is going to be vandalized; internet art you might think how you’re going to protect your work and your audience from trolls or people who steal digital art and claim it as their own.

And then I love the weird and cool interrelationship between the two. We can make digital artwork, show it on the internet, somebody asks whether we can print a mural of it, so we do that, then people take photos they post on the internet, and the cycle begins anew and different groups up people get to have their experience and join the conversation at all the different points along the way.

DigA: How does your control over an artwork change when you employ predictive technologies in a piece such as VIRONOMICON (2020), compared to the “cut-up technique” you use in other pieces such as “Very Serious Paper Cuts” ?

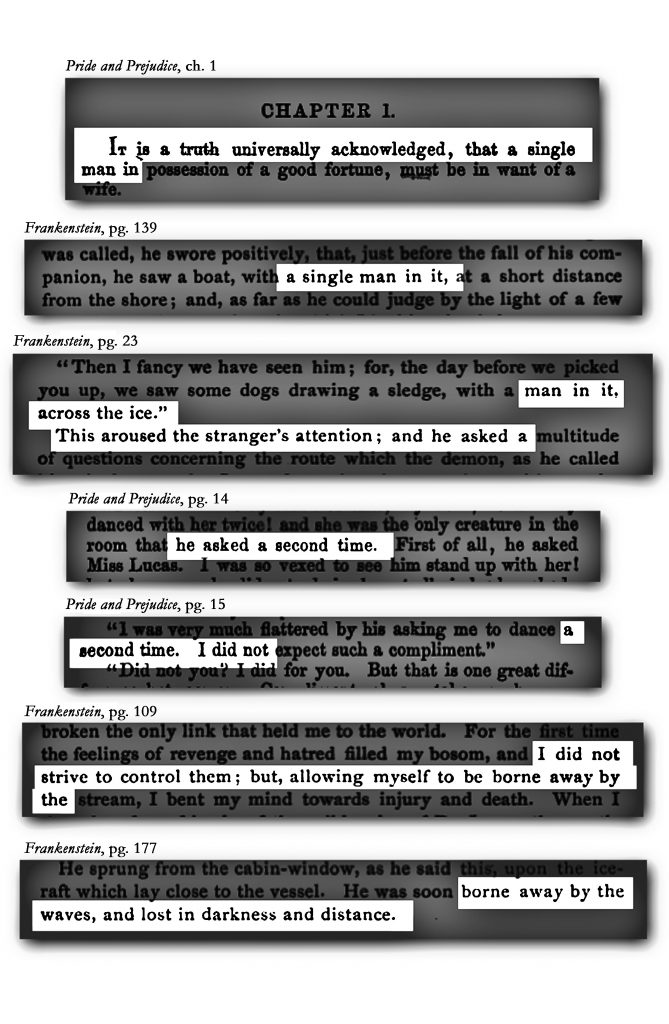

Eric Millikin: Yeah, great question. “Very Serious Paper Cuts” is an ongoing series of mine that I’ve been doing for years, where I create cut up poetry with AI. It’s sort of like the predictive text that our phones use to complete our text messages, but rather than being based on that sort of big tech surveillance of how other people would complete a similar sentence, I’m instead looking at how a very select group of writers and thinkers might structure their writings and sentences. It’s sort of like asking “If I could get, say, Mary Shelley and Jane Austen to finish each other’s sentences, what might that look like? What might we learn from how their words and ideas overlap, intersect, and interact?”

So, my original five rules for the ‘Very Serious Paper Cuts” system were that I would work with computer coding to basically 1) Grab two different books that I am interested in, 2) Start cutting the text from the beginning of the first book, 3) If I get to a phrase that I can find elsewhere in either book, then I can start cutting from that new page, 4) Repeat that process and don’t stop until I cut my way to the end of the second book, 5) The results will be likely surreal and possibly humorous, but we need to take the results very, very seriously.

With that, I’d end up with a series of strange free verse cut-up poems. With later versions of the system I used more sources, like creating poems out of a series of multiple texts from 1692, the year of the Salem Witch Trials, to sort of get glimpses into what was being recorded across different economic classes and different parts of the world at a single point in time. So, that was one way I would sort of widen the system, by using multiple sources as input data, and then I’d also put further constraints on the system, forcing it to instead of creating free verse, to try to follow structured poetic forms, like sonnets and villanelles.

In VIRONOMICON, I designed the system to create limericks, five line poems in that AABBA rhyme, each line taken from a different person who was writing during and about plague times. Each line is in chronological order, with each writer’s ideas influencing other writers in the chain, sort of how language and ideas can behave like a time-traveling virus.

DigA: In the recent push for a “hands free,” socially distant world, we have seen a large resurgence in the use of QR code technology (i.e. menus in restaurants). What inspired you to use QR codes in this piece? How did you approach distorting the codes while still preserving their function?

Eric Millikin: First, I love QR codes. They are just an amazingly powerful and also often completely useless system for sharing digital information and artwork, through these weird little abstract, physical black-and-white designs. I also love that most people just have no idea what to do with them. Not just that people don’t bother to scan them, but that people make them and then put them on like the backs of semi trucks, as if anyone’s going to be driving down the highway, pointing their phone at semi trucks, so they can scan QR codes and look at websites. So, instead the QR code becomes another type of code, where many times it’s not even about what’s in the actual transmitted by the code itself, but instead just trying to transmit the idea that “look, I’m a human being in the 21st century and I know how to communicate through computer codes.”

And also I love the idea of codes. I love secrets, trading secrets. I love the act of encoding, I love the space where you don’t know what the code means, and I love the act of decoding and the moment of understanding.

There’s a branch of code making called “steganography” which is the hiding of secret coded messages in plain sight, where people don’t necessarily realize they are looking at a coded message. So, rather than encoding a message so it looks like a bunch of indecipherable symbols, where everyone knows there’s a hidden code in there, you instead hide the coded message inside what seems like regular plain text, or hide it inside a piece of music, or inside the digital image data of visual art. So rather than the common black and white QR codes, I put my QR codes into visual art so that it can be fine if some people don’t even realize there’s a code there, and it can be an interesting discovery or being in on a secret when you do know the code is there and get to decode it.

The term steganography dates back to 1499 and the book “Steganographia,” which outwardly appeared to be a spell book teaching witches and warlocks how to use angels and demons to transmit messages over long distances, but was instead actually a book on how to transmit messages over long distances by hiding coded messages in plain sight.

I also love using code to create further codes, and using machines to create artwork that is meant to be read by other machines. And here I’ve created a computer coded AI to create encoded JPEG data of images of tarot Death cards that then contain QR codes that then play encoded sound files created from that AI-generated encoded image data. So, there’s codes on top of codes on top of codes and then looping back to the original code, where you can never be sure whether you’ve ever really decoded the thing, or just decoded another coded message.

DigA: You researched “cultural artifacts from our current and historic pandemic outbreaks” to create this piece. Can you speak to what insights were revealed through this process? Was there anything interesting you learned that didn’t make it in?

Eric Millikin: To me, one of the most interesting things is just how normal and predictable pandemics are. I mean, as unique of a time as this may seem to be, if you want to be a fortune teller, if you want to be a prophet, you really can’t go wrong predicting plagues, war, and/or famine.

I was looking at how different artists responded to and worked through different plague times, and was particularly struck by how interrelated they were, how I was sort of just one artist in a pandemic in a chain of other artists during pandemics looking back at previous artists during pandemics.

For example, when I’m looking back at Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Masque of the Red Death,” it’s this fantastic tale of a wealthy prince who thinks he can hide in his castle and throw parties for his wealthy friends and the plague won’t reach them, the plague is for other people, but eventually the Red Death catches up to them. That’s a fantastic story, but also a story that is so timeless. It is such an accurate description of wealth and class and indifference or trying to ignore other people’s suffering that it might as well be a news report about super-spreader parties being thrown at the White House. But that’s also probably a very personal story for Poe, whose mother had died of tuberculosis, and Poe’s wife Virginia contracted tuberculosis shortly before he wrote the story. And he’s also apparently looking back at previous pandemics here, because his main character is “Prince Prospero,” seemingly named after the character “Prospero” from William Shakespeare’s The Tempest, and in The Tempest one character tries to curse another with a “red plague.” So the further I went in my research, the stronger I got the feeling that I was repeating this act in a long, branching chain of one artist in a pandemic looking back at another artist in a pandemic who looked back at another, over centuries of plagues.

To put another way, I’ll walk through the chronology of the cut-up poetry. The first line of each limerick is from Nostradamus, who had reportedly worked as a plague doctor before he started making his prophecies of future plagues. John Dee, who was in some ways Nostradamus’s rival in the world of predictions and astrology for royal patrons, John Dee’s wife Jane was killed during a bubonic plague outbreak and Dee was accused of bringing the plague to London. John Dee was considered to be William Shakespeare’s model for his character of the magician Prospero in “The Tempest,” and Shakespeare wrote many of his plays while the theaters were closed due to plague outbreaks. Edgar Allan Poe then names his “Masque of the Red Death” character after Shakespeare’s Prospero. And then the final line of each limerick is from Diane Wakoski, from the literary journal “Caliban,” which is named after the character in “The Tempest” who tried to put the curse of the red plague on Prospero.

I studied poetry writing under Diane Wakoski while I was an undergrad at Michigan State University’s Honors College, when she was poet in residence, and I was an art and English double major. So she is then the link in that chain from Shakespeare and Poe to me, and we’re both thankfully still living and working through this pandemic. So then I’m sort of the unwritten sixth line of each limerick, and then hopefully maybe people who look at VIRONOMICON, now or perhaps in some future plague, they might be the unwritten seventh line, and then on and on into a future of more pandemics and plagues.

As far as other parts of my plague and pandemic research that did not make it into this project, I am also deep into the history of the fear of blood, and the fear of contaminated blood, from strange conspiracy theories to vampire tales. And I have worked with masks in recent years — creating masks as VR headsets as well as using augmented reality to place masks over faces for performance videos — so during this time of societal mask-wearing, I am delving even deeper into masks and their cultural significance, in recent projects where I am using facial recognition on masked characters in popular films, and growing bio art sculptural masks from mycelium and mushrooms in AI-generated facial forms.

DigA: In VIRONOMICON, you draw a comparison between historical practices of divination and contemporary predictive technologies. As underlined in a recent article by Atlantic, the rise of big data and predictive analytic technologies has coincided with a renewed public interest in ideas such as divination, astrology and mystic readings. Can you explain how you reconcile these seemingly opposing trends within your work ?

Eric Millikin: Yeah, they may seem to be opposing trends, but to me they are really just distant iterations of the same concept. In the way that alchemy was just early chemistry, or the way that witch trials were just early forensic science, then something like tarot card divination is just an early form of predictive AI. You know, “I am going to draw a deck of cards, with each card showing common future outcomes, and then I’ll draw from the deck in order to think about what the future might hold.” At one time, that was cutting-edge data-driven analytics and forecasting.

So for me, if I use machine vision to try to recognize tarot cards, and then use predictive AI to try to determine what other tarot cards might look like, then I’ve entered this nice space where seemingly futuristic machines are trying to predict their own futures, using a mix of old and new technology.

Part of what interests me here is the relationship between technology and magic. A new technology can seem magical, but then an old technology can just seem like a superstition.

DigA: Can you talk to us about some of your current work—particularly if it relates to the present political environment in Richmond, VA, where you are currently studying (and from where Digital America is based as well) ?

Eric Millikin: Yes, I moved from Detroit to Richmond last year so I could join VCUarts’ amazing Kinetic Imaging MFA program for new media art. I came for a lot of the reasons most anyone chooses a graduate school — great school, great faculty, great students, etc. — but I was also really drawn to Richmond as a location. I appreciated the chance to come to the former capital of the Confederacy, just east of Charlottesville, and just south of Washington, DC, as we headed into the 2020 presidential election, to create politically and socially themed new media art as we try to remove an overtly racist president.

One of the projects I did last winter, in the first year of my MFA program, was an augmented reality exorcism of Richmond’s Jefferson Davis monument, in a sort of attempt to stop the ghost of Jefferson Davis from continuing to haunt our city. It was part of my small contribution to the efforts of so many to try to get those monuments torn down. It felt so good this summer to be able to go out with so many other people to cheer those monuments being finally removed.

There’s still so much more for us to do, of course. It’s one thing to remove symbols of racism from your line of sight; it’s another to try to get generations of institutionalized racism out of all of our heads. I am currently working on a series of AI-generated hypnotic videos, in part looking at the horror films of 2016 to try to see what types of fears they depict and how they might relate to the 2016 election. It’s partly trying to train machines to look into the recent past, to maybe help avoid repeating mistakes in the future.

Check out Eric Millikin’s VIRONOMICON.

:::

Eric Millikin is a conceptual activist new media artist, using techniques like artificial intelligence, sound art, artist’s books, interactive video projection, augmented and virtual reality, bio art, 3D printing, occult experiments, and dark humor to address his research into topics like the global COVID-19 pandemic, economic injustice, police brutality, and species extinction. Millikin is currently an MFA candidate in Virginia Commonwealth University’s Kinetic Imaging program. He has recently exhibited in 20 venues within a year’s time, and his work has been exhibited in museums and galleries from Detroit, Denver, and Dubai to San Francisco, Scotland, and South Korea. Millikin’s artwork has been featured in WIRED, USA TODAY, Ripley’s Believe It or Not!, and The New York Times Sunday Arts section.