When I picked up the latest Microsoft Office suite, I found that it came with a whopping 1TB of storage in OneDrive, Microsoft’s cloud storage service. I was already using it through my Xbox One, of all things (I’m able to save game clips and screenshots that are uploaded to my OneDrive folder for viewing and sharing), but when I saw how much storage I was now capable of using, I moved everything from my Dropbox and Google Drive accounts and threw them into Microsoft’s little storage vault in the sky. Photos, documents, comics, a video I’d recorded of a friend of mine singing karaoke at a bar for 30 minutes, most of the drafts I’d written for my DigA column, some music, a few screenshots I’d uploaded from my phone so I’d be able to quickly access them on my laptop….it’s all there, waiting to be accessed from any computer in the world that has an Internet connection.

But what if we, as a society, were to depend on the cloud for more than just storing baby photos and mediocre karaoke? Hospital records, text messages between loved ones (and the men/women we’re texting on the side), logs of our online purchases, geo-tagged map data, Internet search histories, phone records…what if we were to put waaaaaay too much stock in the safety and security of the information we’re handing over to companies and their servers for “safekeeping”?

In other words, what if the cloud burst?

This is the premise of The Private Eye, an Eisner-winning comic written by Brian K. Vaughan (Y: The Last Man, Saga, Ex Machina), drawn by Marcos Martín (The Amazing Spider-Man, Daredevil), and colored by Muntsa Vicente. The first issue was released in March 2013, but the series was recently published in a deluxe hardcover edition (called “The Cloudburst Edition”) that was released in December 2015.

The Private Eye made waves when Panel Syndicate, a digital publisher founded by Martin in 2013, released the comic on a “pay-what-you-want” basis for each issue. While it isn’t necessarily a new strategy (Radiohead’s In Rainbows was released using this pricing structure, and the famous “Humble Indie Bundle” has been helping gamers score great deals on video games while also supporting both charities and game developers since 2010), it was notable for being one of the first DRM-free comics to also allow for readers to choose how much they’re willing to pay for it. Theoretically, you could put down approximately $0 to download and enjoy Vaughan’s story, but you may feel a bit icky afterwards by not giving anything in return (if you have a conscience).

The story is set in Los Angeles in 2076, roughly sixty years after the digital cloud had suddenly “burst.” The private information of millions upon millions of individuals was suddenly made public for forty days and forty nights. No one knew who to blame, but the event itself was a huge wake-up call for countless affected individuals.

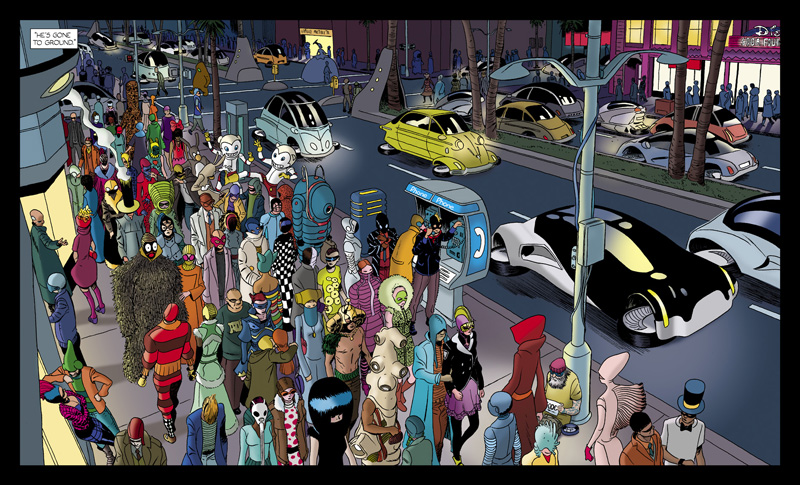

As a result, citizens have taken it upon themselves to fully embrace the 4th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution: “The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized.” Everyone owns at least one costume to mask their true identity in public, and many own several disguises for particular settings (work, errands, a stroll through the park, etc). This makes the city scenes in The Private Eye a true feast for the eyes, as no two citizens of Los Angeles look alike. Animal heads, dresses that would look out-of-place in even the wildest runway shows in 2016, ghillie suits covered in barnacles …you name it, someone’s wearing it.

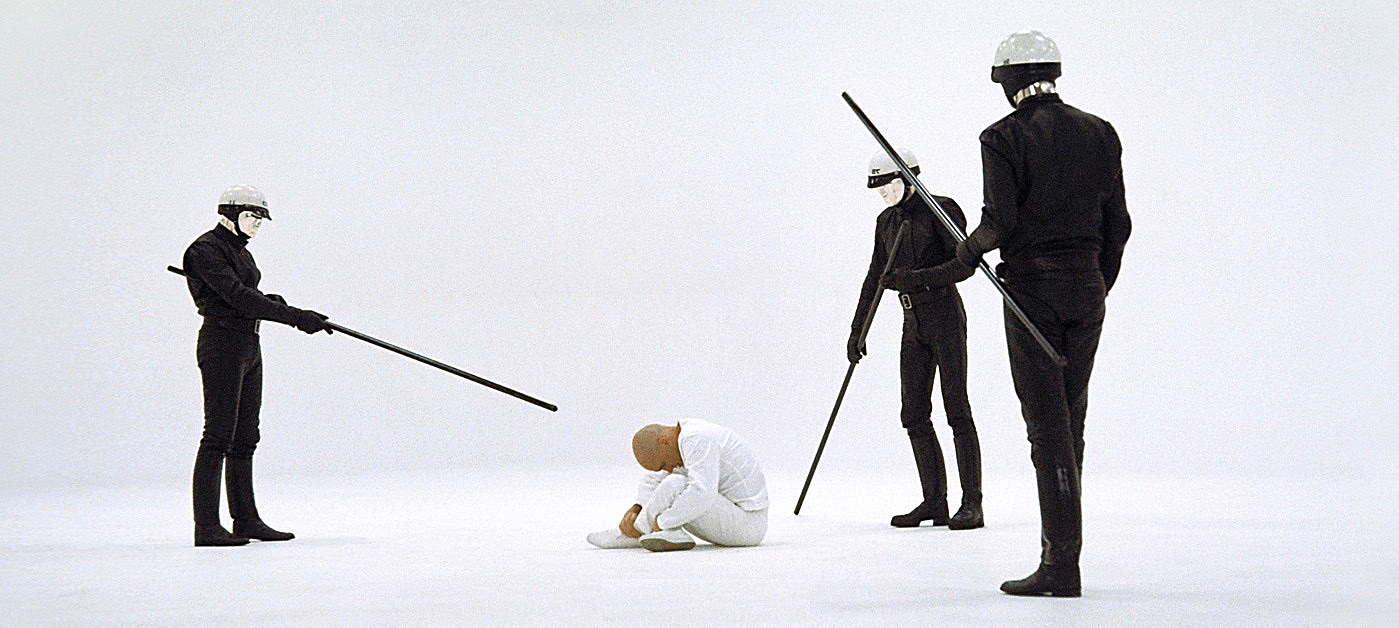

To make things even more interesting, journalists have become federal operatives working for a new branch of government called “The Fourth Estate.” Clad in old-school suits and fedoras (complete with “PRESS” cards tucked into the brim identifying them as trained federal agents), they protect the citizens from groups like the Paparazzi, who are unlicensed and renegade private investigators who are hired to uncover sensitive information hidden behind the outlandish costumes and masked personas. Want to know what happened to your high school crush? Curious about whether or not your neighbor (who goes by the name of Banana Sorbet and normally leaves home dressed as a fire hydrant) recently had a baby? Or maybe you’re just curious what other people can dig up on you and want an off-the-grid PI to do some precautionary searches? Hire the Paparazzi.

The hero of the story, who functions as more of an anti-hero, is a mysterious young man who goes by the name of P.I. (and he often abbreviates it by simply using the symbol for Pi). He’s hired by what can only be described as as the classic “femme fatale” to do some serious digging into her own past in order to uncover anything that may stand out in the eyes of a prospective employer. P.I., who had previously worked with the woman’s sister, accepts the job. This sets up a chain of events that put everyone associated with P.I. in danger as strange and powerful enemies seek to strengthen their grip on a society that has grown up off-the-grid and extremely protective of their true identities.

The present-day setting is familiar, despite the futuristic structures, the maze of tubes running throughout the entire city, and the automobiles that seem to float on air. But the major difference between this Los Angeles and the type of future city that’s often seen in films like Blade Runner is that there is a noticeable absence of cell phones, laptops, and other devices that are currently dominating the tech landscape in 2016. Phone booths and the aforementioned tubes are used for communication, and people move about the city with their heads aimed towards the horizon, not down at a screen. The parks and outdoor areas are filled with people reading, playing frisbee, and enjoying each other’s company, and books have become more important than ever since the Internet was basically shut down for good. Librarians are some of the most important people in Los Angeles in 2076.

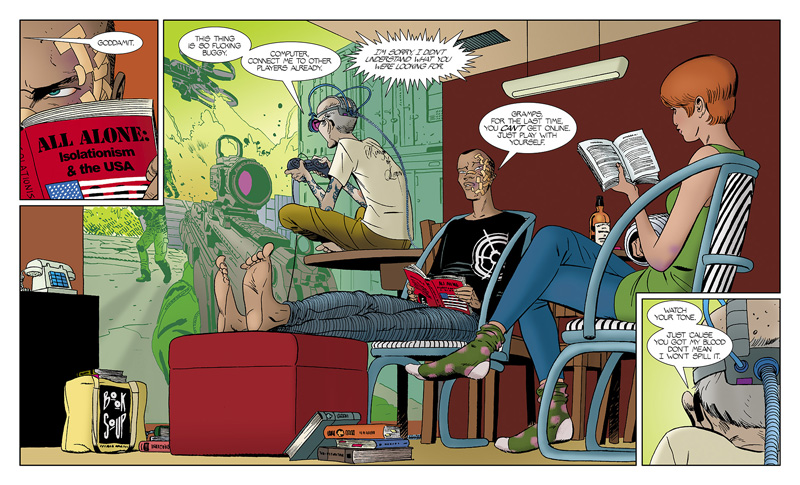

While the comic’s “current” generation of Americans is completely onboard with the whole “anonymity is everything” lifestyle, there are those who were born before the burst that are reluctant to change their ways. Members of “the Facebook generation” (which, according to Vaughan, is the current era in which we live in 2016), including P.I.’s grandfather, refuse to hide their identities in public and struggle to adapt to a world where, as P.I. explains to his frustrated grandfather, “you can’t get wifi in the house because there’s no such thing as wifi, or internets or em-pee-fours or whatever you’re pissed about tonight.” It’s a completely disconnected society that functions just fine without the endless stream of distractions that dictate how we currently go about our days, eat our meals, talk to our friends, and so on.

The Private Eye does not shy away from referencing actual brands and companies found in the real world. Signs for GAP and McDonald’s can be seen among fictional locations. P.I. enjoys reading Joseph Heller’s “Something Happened” and listening to The Flaming Lips (a hardback book and a vinyl record…remember, there are no iPods or Kindles in this universe). Movie posters for The Maltese Falcon and Angel Face adorn the walls of his office. A stack of books on his desk include “Freakonomics,” “The Audacity of Hope,” and Henry Miller’s “Tropic of Cancer.” The setting is grounded in reality in that there are no crazy superheroes with Hulk-like strength or the ability to fly. These are just ordinary humans living lives that only seem abnormal through the eyes of a society where our desire to “share” is just as strong as their desire to “hide.”

The writing, as a whole, is excellent, but there were moments when I actually had to stop reading because my mind was lingering on particular quotes and how they relate to America in 2016. When P.I. finds a librarian and asks him to help him uncover some confidential information (an act that breaks almost every rule in a librarian’s code of ethics), he reminds P.I. that search histories are federally protected:

“When the flood happened, it wasn’t people’s private letters or chat transcripts that destroyed lives, it was their search histories. All we do is lie to each other, but when we’re alone looking hard for what we actually want most in life…that’s when we reveal what pathetic wrecks we really are.”

As a testament to The Private Eye’s awesomeness, that line was delivered by a man wearing a fish head.

It’s hard to review something that can be easily acquired for free, if you’re the type of person who reads reviews to see if something is worth your money. But if you’re wondering if The Private Eye is worth your time, then yes. Yes, it most definitely is. Aside from being an excellent commentary on our present-day technological dependencies (which, in my opinion, is a topic that’s pretty played out nowadays), it’s a beautiful look at a world in the not-too-distant future that’s been drastically affected by something that’s completely within our control to prevent. An earthquake or a tornado or any other natural disaster can be hard to predict, and they leave cities and towns in shambles. Threats of nuclear war between two rival governments or powers can be just as destructive, but oftentimes it can feel like the everyday citizen is powerless to prevent it. But a cloud burst? The effects of such an event can damage almost every aspect of one’s life, and the aftershocks can be felt for as long as the data and information is publicly available.

We’re already taking preventative measures to try and stop this type of thing from happening to ourselves, a problem that WE—you and I—have created. Changing our Facebook names to make it difficult for employers to discover what you did to your boyfriend on New Year’s Eve in 2009, retroactively deleting old Tweets that someone is now using against you during a political campaign, desperately trying to obliterate that YouTube video of you kicking a cat as you try to raise money for the animal shelter you just opened up. These are situations that we will ALL inevitably encounter over the next few years as our world simultaneously continues to be all about “SHARE SHARE SHARE” as our employers and the federal government continue to “DIG DIG DIG” into the personal information that we have been essentially handing over to advertisers and private companies ever since people like Mark Zuckerberg and Tom Anderson dramatically altered the way we go about our daily lives.

No, I will not try to make that sentence any shorter.

In the “Extras” section at the end of Book One, Vaughan published his original pitch for the story that was sent to the artist. He writes,

“If our parents had feared Big Brother, we had become him, a generation of exhibitionists willfully sharing every detail of our private lives with each other. But the Great Flood revealed that we were all only ever sharing one version of ourselves, a fantasy as ethereal as the Cloud itself. Hoisted by our own petard, the network we created to preserve and share our daily triumphs also remembered and revealed our worst failings. Like a WikiLeaks dump on humanity itself, all of our records…we’re all instantly available to anyone and everyone—employers, neighbors, loved ones, or just curious strangers. Careers were lost, reputations were ruined, friendships were ended, and families were scarred forever.”

The Private Eye may be a precautionary tale built upon a highly unlikely premise—considering the fact that there isn’t one “cloud” that can burst, and there are safeguards to prevent such a thing from happening…OR SO THEY TELL ME…)—but it’s an excellent look at how we may end up having to live our lives 10, 20 or 30 years down the road. Have you given any thought to quitting Facebook recently? If not, do you have any idea when you think you’ll be leaving the site?

If Facebook were to go under, or get bought by some yet-to-be-conceived social media monopoly, who will own the life that you’ve been uploading daily since the mid-2000s? Who do you trust with your data?

The Private Eye can be purchased in digital form (you name the price), or in a hardcover edition at your local comic book shops (call ahead, it’s a pretty popular title) or through online retailers.

:::

Andrew Jones is a recent graduate of the University of Richmond’s Class of 2014 with a Major in American Studies and History. A member of the DigA team since its inception, he is the co-founder of Forum Magazine, an award-winning student publication, and is currently a postgraduate researcher at UR. On any given Saturday, you can find him grooving to Fleetwood Mac at the local record store, reading a Stephen Ambrose book by the James River (currently D-Day), or solving the world’s problems through witty reddit comments.