Brooke Inman is an artist and nature enthusiast residing in Richmond, Virginia. Her diverse practice specializes in Intaglio, Screen Printing, Zine-making, Drawing, and Color. Through obsessive organization, heightened awareness of detail, and close observation, Inman’s work transforms the banality of the everyday into a lens through which to view ourselves and the environment. Inman is currently adjunct faculty at the University of Richmond in the Visual and Media Arts Practice Department, and the Virginia Commonwealth University in the Painting and Printmaking Department. She also serves on the board at The Iridian Gallery and teaches printmaking in the Richmond community at Studio Two Three, The Virginia Museum of Fine Art Studio School, and The Visual Arts Center of Richmond. Inman received a BFA in Printmaking from the Cleveland Institute of Art in 2006, and a MFA in Painting and Printmaking from Virginia Commonwealth University in 2008. You can view more of her work at Cargo Collective.

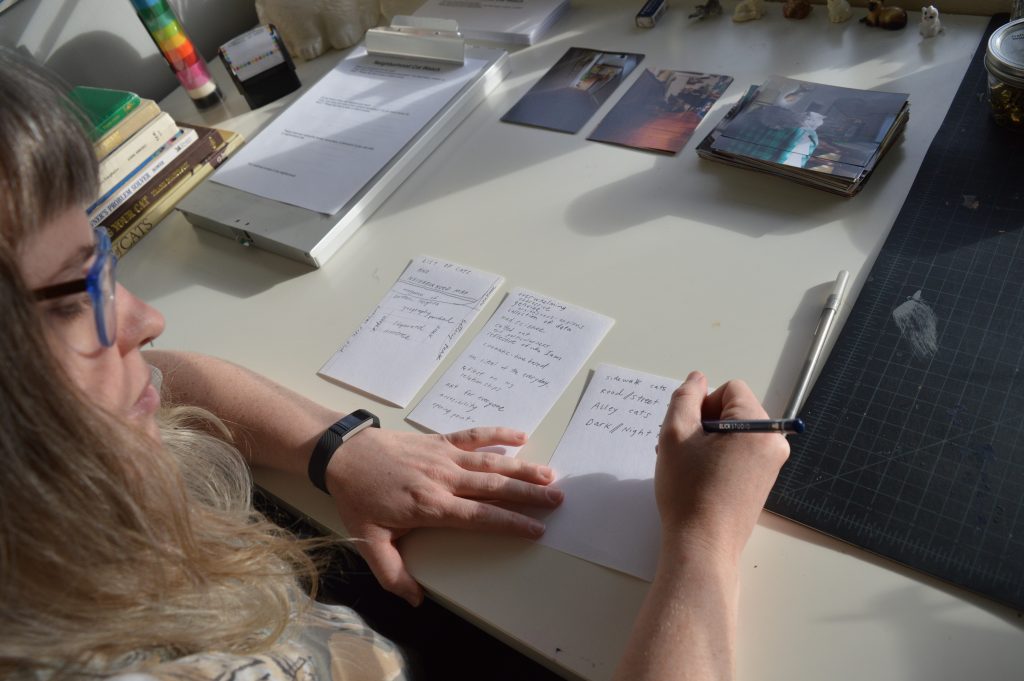

Digital America conducted this interview while visiting the artist Brooke Inman in her studio as Neighborhood Cat Watch was being constructed. The piece is concerned with documenting the feral felines of Inman’s neighborhood, creating an overwhelming web of information that is personal and meticulous.

Neighborhood Cat Watch (2017) is currently featured in the Crooked Data: (Mis)information in Contemporary Art [site no longer live] exhibition at the University of Richmond Museums.

DigA: Could you talk about the different elements of the project (photos, drawings, and survey) and how they contribute to your concept for Neighborhood Cat Watch?

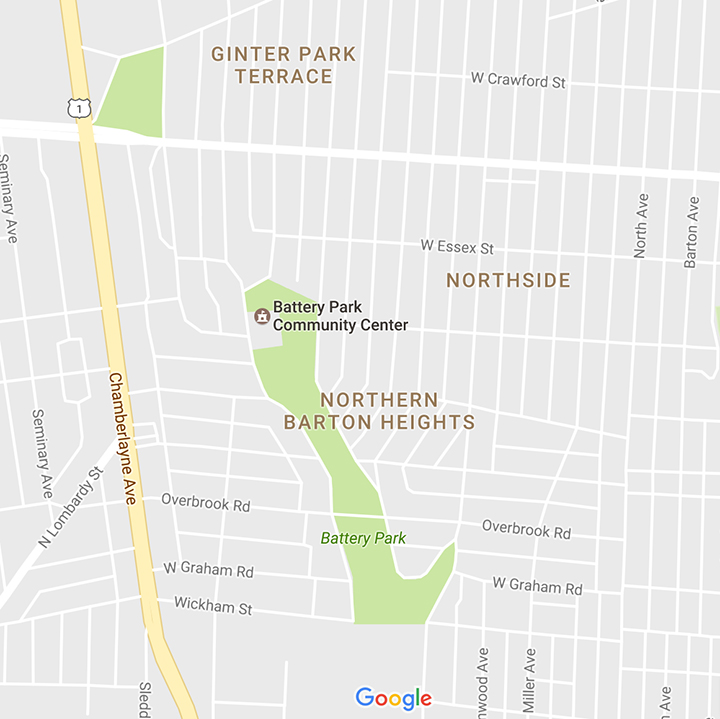

BI: Once I got the photos printed out, it felt a little more real … even though I still don’t really know what I’m doing. But that’s what’s kind of exciting about it, […] It’s so different for me to do this, and I like how it’s on the verge of being really … genuine with a façade of seriousness about it because I made this survey. This seemed like the last step, to put the surveys out in the neighborhood. I’ve been cat-watching and taking the photos for a year. All of 2016 was research-based for me, and then once I really started to think about how I’m going to present this […] It just made sense that the next step was to reach out to my neighbors, and so I made this survey and circulated that around my neighborhood I live in, Battery Park, which is a really wonderful neighborhood. I went to a Battery Park Civic Association meeting and introduced the project to my neighbors, and passed out forms there. Every time I get a response back, I am overjoyed because it connects more dots and makes the project more real for me.

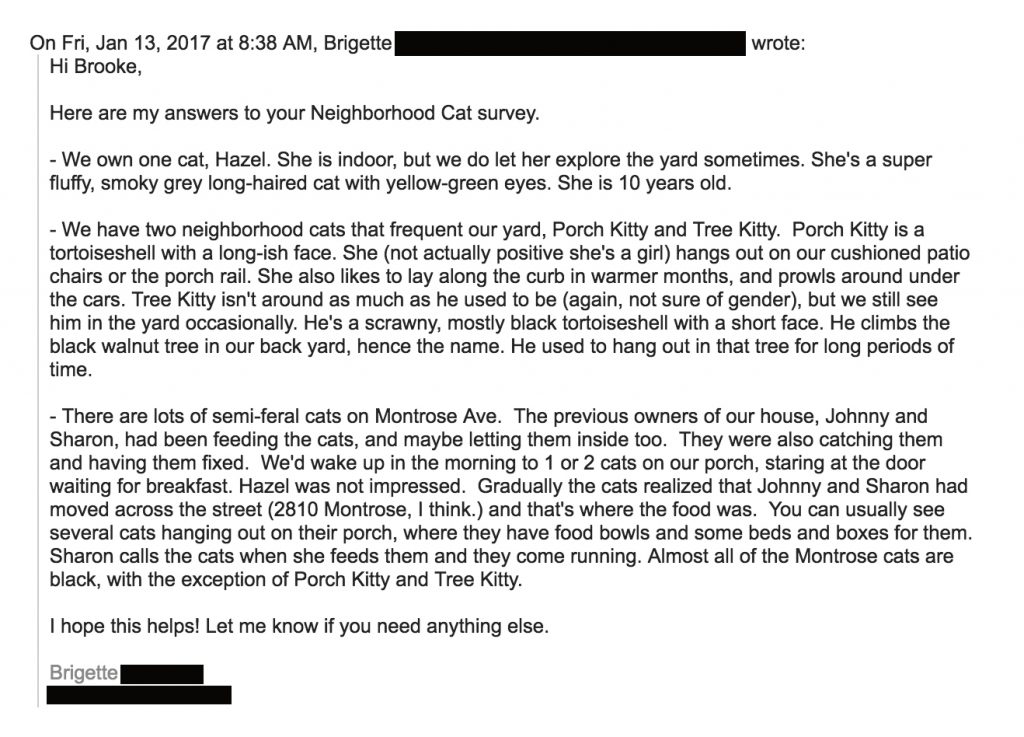

DigA: What kind of data did you expect to collect from the community, and how did it change the project for you?

BI: There’s a level of dryness or seriousness to the survey, but the project itself goes back and forth between being really funny and maybe even useless. The other aspect of it [the project] is that it’s a little bit creepy, because there’s a lot of pictures of my neighbor’s houses. When I would see a cat and photograph it, I would be aware that sometimes my neighbors were watching me take pictures, because I wasn’t doing it sneakily, I was very much out in the open doing it.

DigA: Do the photos feel aesthetic to you, or is the information just about documentation?

BI: I feel really out of my realm with this project, as you know, I’m not a photographer, and I’m not presenting these as being good photographs. There are very few photos here that I think are actually good. They are, for the most part, very shitty cell phone pics that are printed out. They don’t feel precious to me as photographs, but more as information-based glimpses.

![]()

DigA: How does inter-media work inform your other practices, like your printmaking? Do you always collect data in your work?

BI: I do collect a lot of stuff […] collections in general have always been present [in the work]. Most recently I’ve been collecting things that people would consider trash. I’ve collected balloons off the beach, and that inspired a whole body of work. This is my collection of Richmond balloons (pulls out a clear sac full of balloons). They don’t really look like much in the bag, but when I hang them on the wall they are really quite beautiful.

This is the newest thing that I don’t really know what I’m doing with. I’ve been collecting these weed-wacker strings. This is the kind of thing I do. I get an idea, and I’ll just follow through with it even if I have no idea why I’m doing it. So, I sort of see this [Neighborhood Cat Watch] as an extension of my practice, just a very different form… this project does feel very now in that everyone is an amateur photographer. In a way I’m playing with that …

DigA: How does your personal life and routine find it’s way into the observational data of Neighborhood Cat Watch?

BI: So I do have a stack of pictures of Ellie, she’s my cat, AND I kind of think of her as the center point of the piece. Once I’m doing the installation, I think she’ll be in the center and everything will radiate out from her. There is an aspect of it coming from a personal place, since she’s my cat, but also one of the neighborhood cats. In some ways it feels impersonal- for instance, this house that I drive by all the time (points to a photo on the wall), I call this the Cat House because there’s always cats, there’s cat beds, food bowls, it’s the Cat House. I don’t actually know who lives there, I don’t have any real connection with them, but at the same time it’s a house I drive by almost everyday and it’s only one block away from my house.

DigA: How do you feel like the drawings that you have among the photos come into the project? What is the dialogue between the very direct, photo documentation versus the more affective drawing?

BI: In the beginning I thought I was just taking pictures to use as references to draw from. That being said, I just kept taking more and more photos and then it seemed like the photos were the thing that I was doing, not the drawings. I haven’t necessarily decided if the drawings are going to be included or not, but the photos definitely took over. What I have right now is possibilities for how the installation might look, but again I’m honestly not sure… and I’m still deciding on what gets included and what doesn’t. The forms, the drawings, the photographs… the aesthetic I am going for is a crime scene detective who was trying to piece together what cat controls which territory, what yards these cats frequent.

DigA: Do you think in the end you’ll have some sort of narrative, or will it be more about the investigation of feral cat dynamics in the neighborhood?

BI: I think of the narrative as being an identification of the cats. In the beginning, when I first moved to Battery Park, I felt like there were so many cats in the neighborhood. Every time I would walk out of my house, there was a cat. For a while it felt like different cats, but now I’m starting to recognize there’s this cat and that cat that I see all the time. It started out as a really simple genuine inquiry where I wanted to get a sense of what cats were around, but then it turned into this bigger project. I want the installation to feel a lot like this space does [referring to the studio] but more overwhelming.

DigA: The space feels important to the project—there are cat figures, books on cats, cat décor. Do you think the process as is as important as the piece itself?

BI: It feels really conceptual to me, even though that sounds kind of ridiculous…

DigA: Do you think the overwhelming aspect of this kind of data collections speaks to you as an artist? Is this kind of obsessive data collection something that you strive for or is it more innate?

BI: I think it’s kind of inherently there. It’s reflective of who I am.

DigA: This work seems like it has a citizen science element to it that goes outside the boundaries of personal data collection. Could you elaborate on that process?

BI: This has become such a ritual to me, to go out on walks and photograph the cats. It’s been a year of my life that this has been going on. To finally have these correspondences [with the community] makes it feel real and exciting.