Text messaging and internet chatting has turned us all into Frankensteins.

The goal is to emulate real life, to as closely approximate real-life conversation as we possibly can, even though we all understand that (at least on our end), either we’re blowing through these things (“lol what u want from store”), or we’re pouring over the tiniest little nuances to make sure all of our subtexts are painfully obvious, all of our passive aggressive insinuations sharp as knives.

Only we never have to cop to doing the second thing. We can all hide under the pretense that we’re all doing the first thing, all the time.

Plausible deniability.

If you read too much into our texts, well, sorry, it was basically a butt dial.

(Didn’t mean nothing. Sorry u offended.)

But if you missed something… missed some glaringly obvious clue about our fragile emotional state, well… I mean, hey dude, quit just blowing through our text messages, okay? Take some damn time to read it, because we took some damn time to write it! Obviously!

Only none of it is obvious. It is all a confusing jungle of running ink. The subtext we imbue into these little soulless ghosts is sometimes esoteric — like a hilarious GIF set we knew would add nothing to the conversation, but gave us a big, mean grin — and sometimes we’re spilling our guts. Unzipping ourselves, plopping our steaming, bleeding insides into a shared chat log, and surprise! Like the happy recipient of a house cat’s dead mouse, you’ve gotta deal with it now. You’ve gotta deal with me now. And you were woefully unequipped, unprepared, because the last text I sent you was a picture of Willy Wonka saying something sassy and obnoxious that made me die with laughter 2 a.m. on Saturday morning.

I mean… now that I’m writing this, that doesn’t seem so dissimilar to real life at all.

One moment we’re sweet, the next we’re sour. How much coffee have you had? How much sleep did you get? How many days into your hangover are you?

And, even worse than that, how close or far away are you from whatever quiet goal you’ve always got on your mind? How do you feel about you, right now, in this moment?

Because how you feel about you, I’m sure, is going to impact how you communicate with me (much less how you actually feel about me, which is probably more dynamic than we really give any of our interpersonal relationships credit for).

Real life appears to be a confusing jungle of running ink, too.

Is the difference oxytocin? That in real life you can touch — handshakes, hugs — and cause little explosions of that chemical in your system? That in real life you can read cues — that real life follows the natural, spontaneous curve of our shared freakshow impulses, while digital communication remains largely one-sided?

Digital communication, even at its most intimate, seems to share something with late-night, pay-for-sex phone calls. The distance is always there. Even if it’s satisfying, you’re still hungry. And whatever the results, it’s always self-pleasure or self-mutilation when you’re sitting in a room alone.

This communication, at its worst, seems to have turned us into people who read too much or too little into flash bangs of conversation — it’s made us all paranoid for secret meaning.

Or maybe not paranoid — maybe hungry. Think about the last time you chatted on the internet with a crush. Or shared a long series of text messages. You pore over every detail, every misplaced or correctly arranged period. It turns you into a madman — a detective stuck in an electric room all by himself, at some point more Rorschach test than conversation. More an invitation to torture yourself, because sometimes inflicting your own pain seems a more reasonable way to experience control, than waiting by a screen, or waiting for your phone to chirp, so that this slow, sporadic, confusing conversation can progress. Hungry — yes, salivating, and understandably so, when we fall prey to our imaginations while we wait for the other person to respond. While we give that other person imaginary attributes to fill the void — absentee, imaginary friend making Real Life Friend confusing. Disappointing or intimidating, depending on a laundry list of variables, half of which you’ve probably made up in your head.

Why, it’s almost like you’re just talking to yourself.

And 95% of the time, you’re probably meaner to yourself than your Real Life Friend would ever be.

Control is the thing we don’t have here. We can spend all night crafting our response — articulate, serious, emotional — and then you click a button and it’s gone, and it’s the waiting. The readiness. The imagination game, where we wonder what the other person will think of it. What they will think of us? We wonder if they’re lying, feel it’s horrifically unfair if their response is only a fourth as long as our part of the conversation. We pore over past texts, reading them rapid-fire, as though they occurred that way in real time, as though their cadence can be read and interpreted and understood with the acuity of an Aaron Sorkin conversation. Only it didn’t happen that way. It can’t be interpreted that way. You’re not taking into consideration the large chunks of time that passed between each contribution to the conversation. The ice cream breaks. Or rush hour, or work, or chores, or naps, or — worst of all — the times the conversation lagged because the other person just didn’t want to talk to you.

Because that’s the other part of it — digital communication has left us all open to each other, all the time. The very fact that we all have our phones on us means our lives are open invitations. Which, on its face, is psychotic — there’s a reason we all have doors on our homes. A reason our homes are made of walls. But I know, as the sender of what I consider an important text (important because I sent it), I’m waiting eagerly for a response I figure I deserve. I know you saw the thing. How long can it take you to send me a few words back?

But I also know, as the receiver, sometimes agitating a couple of key strokes into a response worthy of anything seems exhausting. Sometimes conversation seems exhausting. Sometimes it actually is. Sometimes you truly want to be alone, in a place where even the digital fingers of friendly conversation can’t find you.

Alone, then, is what we are not, even if we mostly kind of are.

How confusing.

How desperate and romantic, too, when you finally see the other person, face-to-face. When you let those other little things — the scars, the highs and lows — melt away. Like hard exfoliation, dead things drop off, and you’re left with the reality of a person far more striking than whatever phantom stood in his or her place on the screen of your phone.

The phantom you conjured up in your own mind with the help of the six words they actually sent you.

This constant participation in long-distance communication also reveals something of the lying game that writers play all the time. A lie because our communication can be calculated and slowly thought out, but can be consumed rather quickly. Maybe not a lie — maybe we’re actually finding stickier, more awful truths in the patience this kind of communication affords.

But the reader is certainly left at a disadvantage. We can spill in slow motion, but you’re pretty much left to soak as quickly as a paper napkin (okay, that’s not fair, and reading speed obviously varies — what I mean to say is you don’t see all the second-guessing, and changing, and essentially stuttering and sputtering that went into it, meaning it might seem confident when it’s actually a wreck).

Of course the disadvantage of the writer is there are no take-backsies. Once the toothpaste is out of the tube, you’ve got yourself a minty mess.

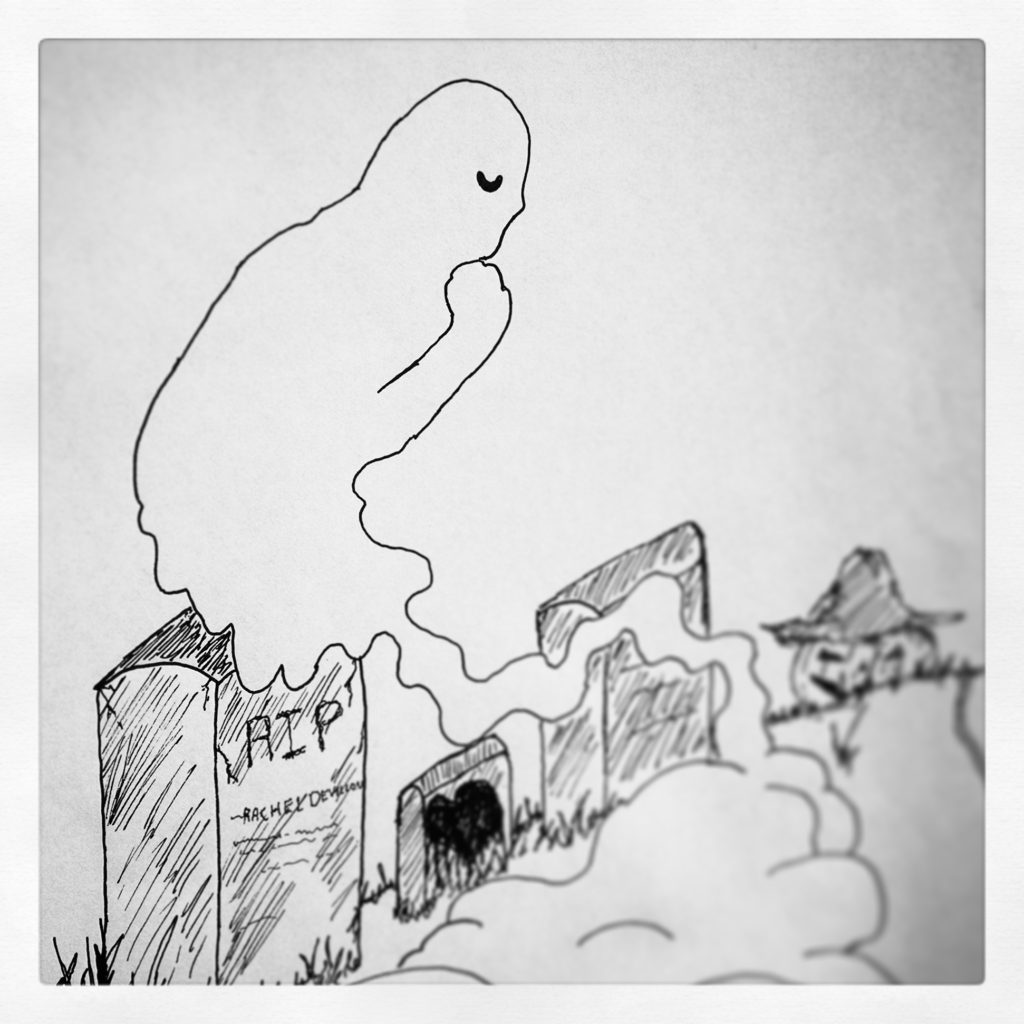

Case in point: it’s October, so I’d like to turn our phantoms into ghosts.

Ghosts basically being wispy, colorful stand-ins for human regret. We give our inability to change the past a face (hopefully more Casper, but probably not — your ghosts are probably as stinking and peeling and gooey as mine).

So, in the digital age, and because we’re all writers, all the time, we live with ghosts. Ghosts that we can’t exorcise from the internet. Ghosts going all the way back to body shots and glitter bongs from Spring Break 2006 that your obnoxious friend photographed and plastered into the digital ether, you know what I’m saying?

Some ghosts mean we’ll never be president.

The internet means we’re all essentially haunted. A landscape of rotten, half-cooked impulses given shambling half-life. Yes, we’re all creatures possessed by our pasts, even if we don’t want to be.

I have a ghost.

Hold my hand, and let’s have a seance, shall we?

Last January, I wrote about Taylor Swift’s New Year’s performance (yes, my ghost is Taylor Swift). I wanted to use it as a lead-in to talk about 2014 in general, and I had this fuzzy notion that I could narrow down the complexities of an entire year using pop culture as a vessel.

This has something to do with being a bad writer, but with Big Ambition. Something to do with being lazy.

I guess I was hoping I could write my way around the year and find the heart of it. Isolate it, examine it, present it to other people. Maybe more house cat than hunter.

I think, if someone else had attempted that, I would have watched them with wide-eyed enthusiasm. I would have thought they were snotty and bratty and possibly brilliant (I labor under the delusion half the time that those are all the same things). I mean, if they had pulled it off.

I’m here, several months later, to report that, not only did I not pull it off, but it definitely reads more snotty to me today than anything else.

The snottiest part about it is that I refer to Taylor Swift’s belly button as a “little nub”.

Which… I mean, I don’t know what to say about that. Bad Writing comes to mind again (nub being an unusual noun: peel back that word scab and you’ll find a discussion waiting to be had about outties and innies, which has nothing to do with what I wanted to talk about, I promise you).

(For the record, I don’t think Taylor Swift has an outtie, but again… why are we even talking about this? I feel ugly now bringing it up.)

And that begs the question: what did I want to talk about?

I think what I probably wanted to reflect was that I really loved her album. That it meant more to me at that time than I wanted to admit. That I wasn’t sure why, that I have sort of high-and-mighty casual distrust of pop culture, so I thought I could only approach it from a distance.

Using snotty humor to dance around the fact that I really, genuinely loved her performance. That something about the music and her act and the friends I was with that night, and the year I had experienced, and the year as I had seen it through the nightly news, had stirred a feeling like romantic urgency in me.

And maybe it’s because I’m a millennial, part of a now generation that stereotypically has no patience, that I sort of blew through all of that and ended up writing a piece that makes me very uncomfortable to read today.

It makes me uncomfortable because (apparently) I decided I’d use her body as a lead-in, to talk about her music as a lead-in, to talk about the year (probably as a lead-in to talk about… something).

(Something lazy and unrefined and snotty and definitely not brilliant).

I wouldn’t have written about a man that way, and it makes me very uncomfortable. I wouldn’t have written about how a man didn’t want to reveal his belly button. Definitely wouldn’t have written about a man’s belly button as a “little nub” (because, also, what in the hell does that mean?)

I talk about how she didn’t reveal her belly button because “she wasn’t that kind of a pop star”, which again, means what exactly? I’m not sure if I was making fun of her (which makes me uncomfortable and more than a little ashamed because there’s nothing there to make fun of), or if I was just trying to Impress with how much I knew about pop culture. See? I’m discussing Madonna. I’ve read articles about how Taylor Swift doesn’t want to show her belly button, but also about how she’s emulating eighties pop music. That we like the same eighties pop music. And I recognize that performative bodies are a part of pop music, and I’m not really saying anything, see?

I think I thought I was celebrating pop music. Reveling in it. But really I was just hiding behind her body.

I said she sashayed on stage “revealing a sliver of mid-chest rib in Manhattan.” I then compared her to Kyle XY, and that’s the only part I’m proud of (because I hope we all remember that show forever, and importantly to this discussion, how he never showed his belly button).

The point is I don’t think I’d ever nitpick a man’s body the way I nitpicked hers. Not really her body; more her decision about what to show and what not to show.

That’s not, like, a funny decision. It’s personal. It matters.

I’ve written again and again about objectification, about how our bodies are the only thing that we really ever own, and somehow I missed the point, and belittled her decision to basically own her own body.

And, by doing that, I only really clarified one thing about 2014: it was a time when I thought I wasn’t sexist, but actually was. Not because I sexualized Taylor Swift (I don’t think that’s what’s happening in the article), but because I used her body as a prop to talk about something else. I didn’t address the content of what she was doing. And I don’t think I would have written the article that way if she was a man.

It’s October. It’s almost Halloween. Our ghosts are all around us. I’m possessed with the idea that I need to have a body of work to leave behind before I die. I also know that many people die young, and because I have no idea what my own expiration date is, I try to produce a healthy amount of stuff.

I am scared, because sometimes that means leaving behind things that are embarrassing. That are awkward and pretentious and sometimes biased, sometimes bigoted, sometimes casually so and (worse maybe) ignorant of their own offenses.

I’m afraid I’m haunted by those ghosts tonight, and I’m sorry about them, and I’ll try to be better about them in the future.

That’s all I’ve got.

How you talk about others (and, for our purposes, how you write about others) is a pretty good yardstick for what is going on internally.

And all that internal stuff, as frightening as it sometimes is, is a million times more important than anything you could possibly hope to observe about someone else from their outside.

What we’re leaving for the world, then, are our insides, strewn all across this electric graveyard.

I hope that future readers don’t mind all the blood.