Digital America interviewed Avital Meshi in November 2022 to talk about The New Virtuvian (2022) and Deconstructing Whiteness (2020).

:::

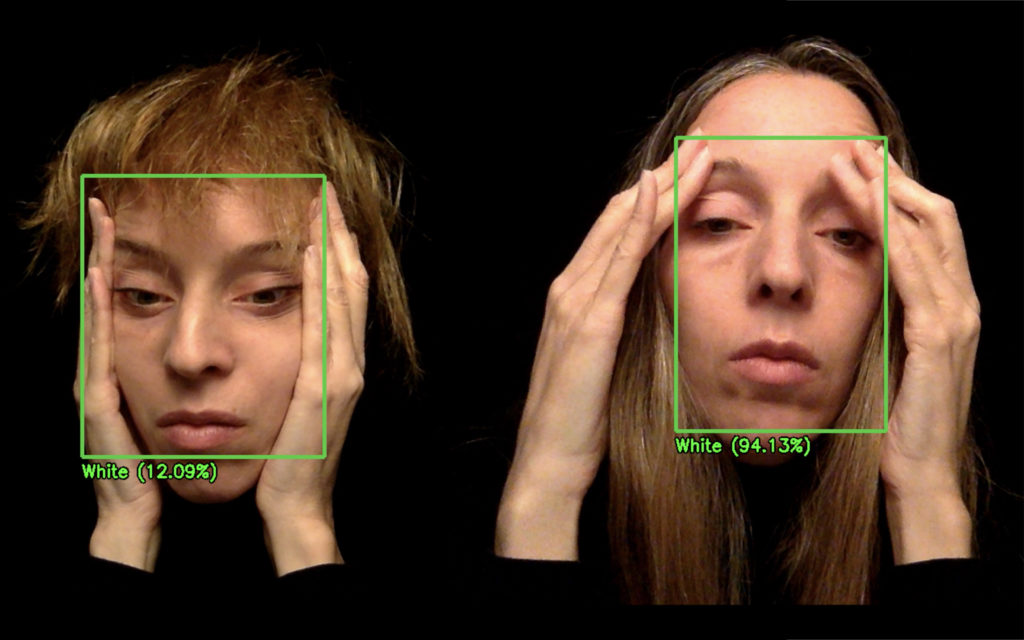

Digital America: How have viewers in the digital art space reacted to Deconstructing Whiteness (2020) over the past two years since its publication? What is the most impactful conversation you have had or heard stemming from the piece?

Avital Meshi: Since its publication, Deconstructing Whiteness (2020) has received attention in exhibitions and conferences committed to a deep and thorough conversation about racial inequality. It was shown in an exhibition titled “Digital Rights are Civil Rights” by the Institute of Aesthetic Advocacy. This Minneapolis Art Collective uses interdisciplinary art to turn the gallery into a site of post-digital social criticism and cross-cultural dialogue. The piece was presented with a few other fascinating artworks focused on racial visibility through facial recognition algorithms. The idea was to manifest the discriminatory aptitude of such algorithms. In collaboration with the ACLU, MN, the exhibition was part of a successful campaign that led to the banning of facial recognition algorithms from police use in Minneapolis. It was significant for me to be part of this exhibition and actively be involved in making a change.

Another venue that exhibited this piece is the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition annual conference (CVPR). This conference is regarded as one of the most important in machine vision and usually hosts computer-science students, academics, and industry researchers. The artwork and a talk about it was shown in a workshop titled “Ethical Considerations in Creative Applications of Computer Vision”. The workshop invited computer vision researchers, sociotechnical researchers, policymakers, social scientists, and artists to discuss the social impact of computer vision applications. For me, it was essential to be part of this conversation as I firmly believe that those who develop AI algorithms are not usually versed in the socio-political implications of their creation. I do not think they have mal intentions, but I argue that they should be more aware of the socio-political impact of their work. This kind of awareness is raised in such interdisciplinary conversations.

I think that my most interesting moment with Deconstructing Whiteness (2020) came up with an invitation I received to talk about my art with art students at a community college in California. In preparation for the conversation, the host told me that it would be great if I could tell the students about my work but also requested that I refrain from discussing Deconstructing Whiteness (2020). I was overwhelmed by this request as it felt like censorship. I asked the host for a reason for this request, and they said that the class is very diverse and people might need more time to be ready for a conversation about racial inequality. When I joined the class, I shared some information about my other artworks, but then I could not help myself and decided not to respect my host’s request. One of the things that I worry the most about is the lack of conversation. I think our ability to discuss complex topics should be readily available at any time. We cannot ignore our reality. If racial inequality exists, we should be ready to talk about it. Otherwise, how will we be prepared to act against it? Even if people are not used to talking about it, even if they end up saying things that might sound weird or inappropriate, someone will always be willing to explain or share their personal experiences. We learn from having such conversations. If we shy away from talking about racism, we give a hand to its embeddedness in our society and essentially allow its cultivation. I am sure that my host felt uncomfortable when I started talking about this piece despite their request. I did apologize for putting them in this awkward position, but I also explained that my art is more than just an aesthetic image; for me, art is a means for provoking essential conversations.

DA: The New Virtuvian (2022) and Deconstructing Whiteness (2020) share the use of the same human-engineered AI technology and the common theme that technology’s interpretation and labeling of humanity is flawed. Do you have hope that engineers’ contributions to the evolution of AI in the future will eliminate some of the bias embedded in AI technology as the systems continue to “learn”? What hopes or fears do you have surrounding the ethics behind AI’s evolution?

AM: The AI algorithms I work with are designed to look at the body’s appearance and make estimations regarding this body’s identity. I find this practice disturbing, but it is not limited to AI algorithms. People do that all the time. When we look at one another, we judge each other based on our background, experience, education, political values, and emotional state. On the one hand, this is part of our natural behavior, but on the other hand, we should never take these judgments for granted. We do not know who the person standing in front of us is, how they identify, where they come from, how they feel, and so on. Therefore, I consider conversations to be critical. Instead of thinking that we know this person, we can ask them and let them tell us (if they want to do that). In this sense, AI algorithms provide an opportunity to reflect on our behavior and rethink our biases.

I do hope that AI technology continues to develop in exciting ways – I am fascinated by this technology and am curious about how far it can go. At the same time, I worry about its implementation in our society without proper regulation. I think that computer engineers should realize the vital role of ethicists and invite them to critique AI software in ways that can eventually prevent any dangerous use. Moreover, together, engineers and thinkers from the fields of social studies, art, and humanities can reimagine the role of AI in our society. Instead of repeating some of the same harmful habits (e.g., war, racism, exploitation, to name a few), maybe we can better consider the role of this technology in bringing us together, enhancing our creativity, and facilitating a culture of care.

Above all, I think it’s time for us to realize that AI is here to stay. Some claim that it is becoming ubiquitous and necessary as electricity. My biggest hope is that people realize that they cannot afford not to know how this technology impacts their lives. It is our responsibility to become versed with it, to figure out what is at stake, and to resist it if need be.

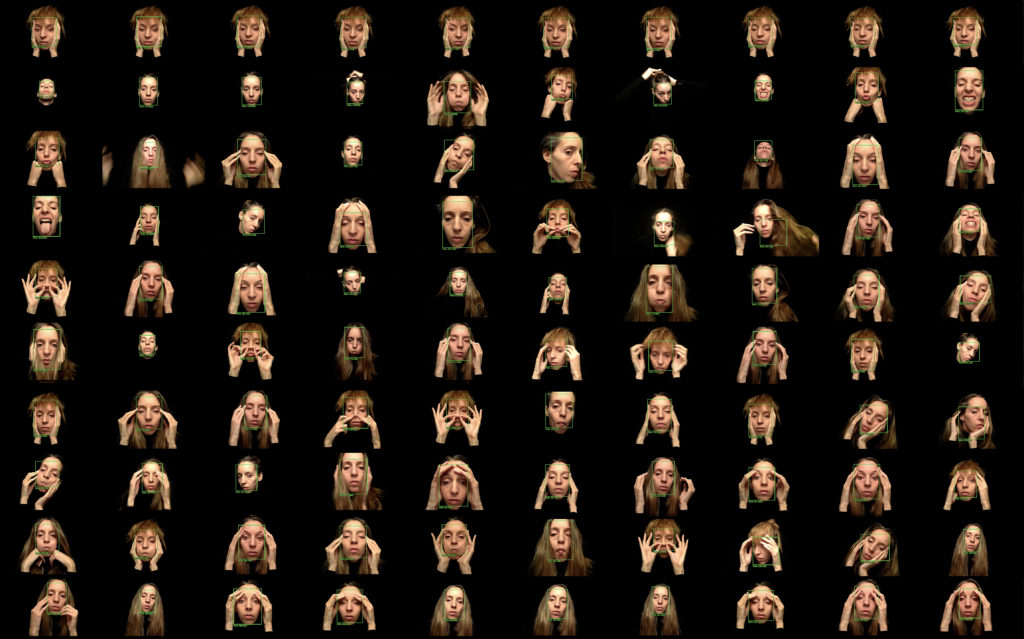

DA: In the New Virtuvian (2022) we see you making a range of fluid movements and taking various positions. You quote Brian Massumi: “In movement the body is in an immediate, unfolding relation to its own non-present potential to vary.” Did you have preconceived thoughts on how the AI would interpret your movements? What was the most shocking interpretation, and what do you make of it?

AM: Algorithms that recognize the body are designed to take our appearance as one of their inputs. With this understanding we can realize that we own some agency over the outputs of these algorithms. Changing our appearance or simply moving, allow us to control the way these algorithms see us. Massumi claims that the body is positioned on a grid of pre-constructed identities. It corresponds, or is pinned to a specific site on this grid. He asks how can a body perform its way outside of this position? Where is the potential to change? Inspired by Massumi’s ideas, the New Vitruvian (2022) manifests a way by which the body leaps from one position on the grid to another. In this piece I simply move my body in front of the algorithm. While moving I have no idea how the algorithm sees me. Only when I rest and analyze the images that were captured I realize that my body is in a constant ‘repositioning’;. the algorithm recognizes me as a person, a dog, a cat, a horse, a bird, a chair, a sofa, a kite, a vase and so many other objects. The shocking experience for me is that my body can be registered as all of these without giving me the opportunity to say who I am. On one hand it shows me that there is something wrong with the algorithm. Something that needs to be fixed. We already have enough examples of algorithms that misidentify people in ways that are offensive and harmful. But then on the other hand, I also think of the opportunities that are given here to reconsider identity. To deconstruct it, to unpin it, and to allow it to change.

DA: You mention the “construct” of the human body in the New Virtuvian (2022). How do you hope this piece draws attention to or comments on social conceptions and expectations of the human body?

AM: I don’t think anybody would say that I am a bird. I never identify as one. But what if I say that I am? Would anyone take it seriously? Would it be respected? What if an AI algorithm claims that I am one? Would it make a difference? This kind of imaginative thinking accompanies The New Vitruvian (2022) as I ponder biopolitics and identity transformation concepts. The piece can be read as a funny, playful experience in which I seem to ‘trick’ the algorithm and ‘score’ as many different labels as possible. But beyond that, I hope it can also be seen as a critique of how identity is being “read.” Not just by AI algorithms but by all of us. My interaction with the algorithm is a conversation, a dialogue. I move, and the algorithm responds. I move again, and the algorithm responds. With time we become more familiar with one another. The algorithm attempts to classify me as I move in front of it. I try to correspond my movement with the algorithm’s vision. It is a process of learning how to live together. I want to think of identity as something that can only be thoroughly understood within a conversation.

DA: What is on the horizon for you regarding any continuation of working with AI?

AM: I currently explore algorithms that generate images in response to text prompts. The algorithms designed to do that became famous over the last weeks, with astonishing results that might have a revolutionary impact on the design industry and the art market. Some of the best text-to-image algorithms include Dall-E by OpenAI, Imagen by Google, and DreamStudio by Stability AI. While working with these algorithms, I continue asking questions about identity manifestation. For instance, there is an AI model I examine that can be trained on a batch of my personal portraits. Once I give it a text prompt, it creates an image of myself in different contexts. I can use words like beautiful, ugly, young, old, sad, happy, poor, rich, and so on as the prompt. The AI will produce different-looking portraits as a response. In a sense, these images reveal our collective thinking and social standards. We can see how the AI algorithm “understands” beauty and visualizes it. Obviously, the algorithm in itself does not know what beauty is. It relies on the data on which it was trained and preconceived connections between text and image.

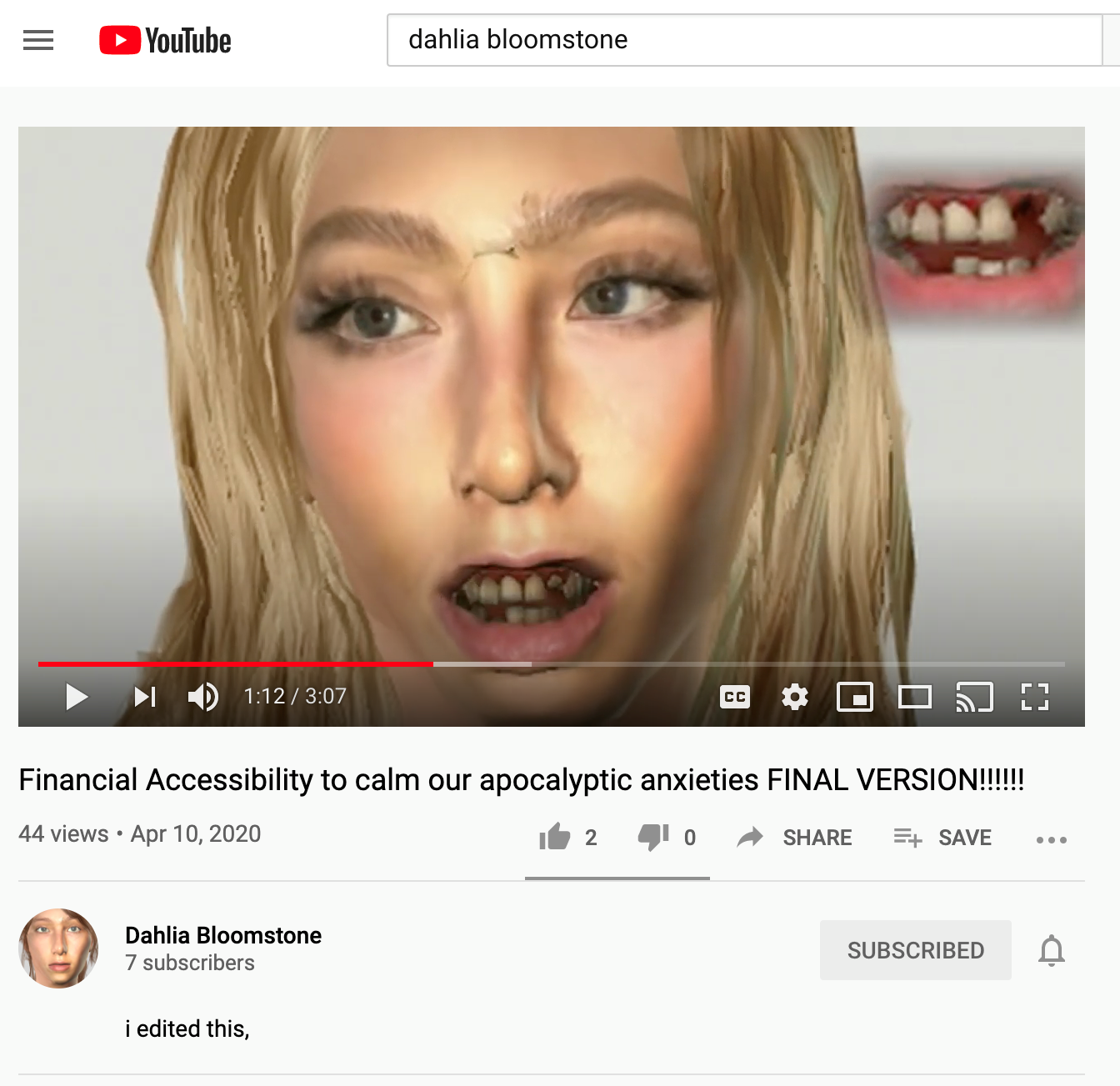

This is a sketch from the project I am currently working on:

:::

Check out Avital Meshi’s Deconstructing Whiteness (2020) and The New Virtuvian (2022).

:::

Avital Meshi is a California-based New Media Artist. She creates interactive installations and performances, inviting viewers to engage with new technology and see themselves through its lens. The entanglement between the body and technology reveals unique aspects of identity and social connections and allows moments of agency to emerge. Meshi is a Ph.D. student at the Performance Studies Graduate Group at UC Davis. She holds an MFA from The Digital Arts and New Media program at UC Santa Cruz and a BFA from the School of The Art Institute of Chicago. She also holds an MSc in behavioral biology from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.