Asger Carlsen’s photography utilizes in-camera and post-processing techniques to create unsettling images that sit uncomfortably within his candid, seemingly truthful world. His series Wrong, for example, takes subjects straight out of Men in Black and photographs them with the ease of Garry Winogrand. The first time I saw Hester, a series of sculptural-images that take Hans Bellmer to the digital age, I couldn’t help but be reminded of Eva and Franco Mattes’ Darko Maver project. Under the guise of a mysterious Serbian sculptor, the net.artists convinced the art establishment that a series of images of mutilated bodies, culled from the internet, were in fact hyper-realistic sculptures left in hotel rooms and abandoned buildings across ex-Yugoslavia. Rather than appropriations, however, Asger’s images actually are meticulously crafted. Treating the digital image as raw material, his work erases the limitations of traditional photography and blurs the lines between photography, drawing, and sculpture.

I messed up part of the recording, so the middle section is from my notes.

You can checkout more of Asger’s work on his site.

diga.rt: I read that you started working as a newspaper photographer when you were 17, which I think is still pretty evident in your style of photography, and that when you first started messing around in photoshop you were initially quite put off by the results. I also read somewhere that your earlier work had a sort of Thomas Struth/ Andreas Gursky type aesthetic, so, you know, very straight photography. Could you talk a little bit about discovering your style in post-processing?

AC: I guess I was always looking, even when I was doing more straight-up photography, I was always looking for this image that could somehow escape the idea of photography. So I was always looking for that in the crop, or the mood of the picture. I was trying to eliminate story, or at least the obvious story I would try to eliminate.

I’ve always been someone that’s kind of been upsetting people a little bit, because I spend so much time messing around with images in post-production. I would just sit there for a long time, and just stare at the image. I don’t know, I guess I was searching for something. I was looking for a way to handle it, in a way that it wasn’t supposed to be handled or something.

So it basically just started with some images and there was a clone tool kind of thing, and I was like, maybe this is interesting. It was this face with multiple eyes, and it seemed at the time that maybe it was too far away from what my goal was, of what to put out there, so I didn’t really show it to anyone for a long time. And I kinda kept them to myself. And then I did show them to one friend, and he was surprised by them and he initially liked them and then put them in an art show that he curated. It was just four images.

And I don’t know, it was just an extremely removed experience in terms of what I had pursued up until that time as a photographer. So that’s sort of how it started, and it took me a while to get used to it, or to get comfortable with it.

diga.rt: Do you think you found it off-putting because of the strangeness of the actual images? Or was it more about the defilement of the photograph or something about the process itself?

AC: Both. Especially the idea of what a good image was or something, you’re supposed to make images that somehow cater to a market, or you’re not supposed to make photographs – I mean, first of all, I want to say that a lot of these photographs, I don’t really – I still don’t – consider them good photographs, in the sense where you’re a photographer and you’re on a mission to make good photographs. And that’s now how I see them. And especially at that time, it was very far from anything I was doing.

Over the next ten minutes we talked about his projects Wrong and Hester. Wrong is a series of photographs that have been altered to include alien forms, both humanoid and otherwise. With a photographic style akin to the famous early-20th century crime photographer Weegee, the images retain an objective sense of “truth-telling”, which only works to elevate their surreality. I told Asger that I found a strange mix of both humor and horror within this series, asking him if he finds something particularly funny about human fears. To my surprise, he said that he finds little inspiration in sci-fi or horror movies. “I’m inspired by what’s boring”.

We then talked about the incredible book Evidence by Larry Sultan and Mike Mandel. Sifting through the photo archives of various corporations, American government agencies, and educational, medical and technical institutions, the two artists appropriated initially banal images and printed them, completely decontextualized, in the mode of a glossy art book. The result is an unsettling collection of images from product tests and scientific experiments, which, when divorced from the information they were meant to provide, appear somehow conspiratory or ominous. Rather than the alien itself, Asger’s photographs seem to be similarly interested in the surreality of the everyday.

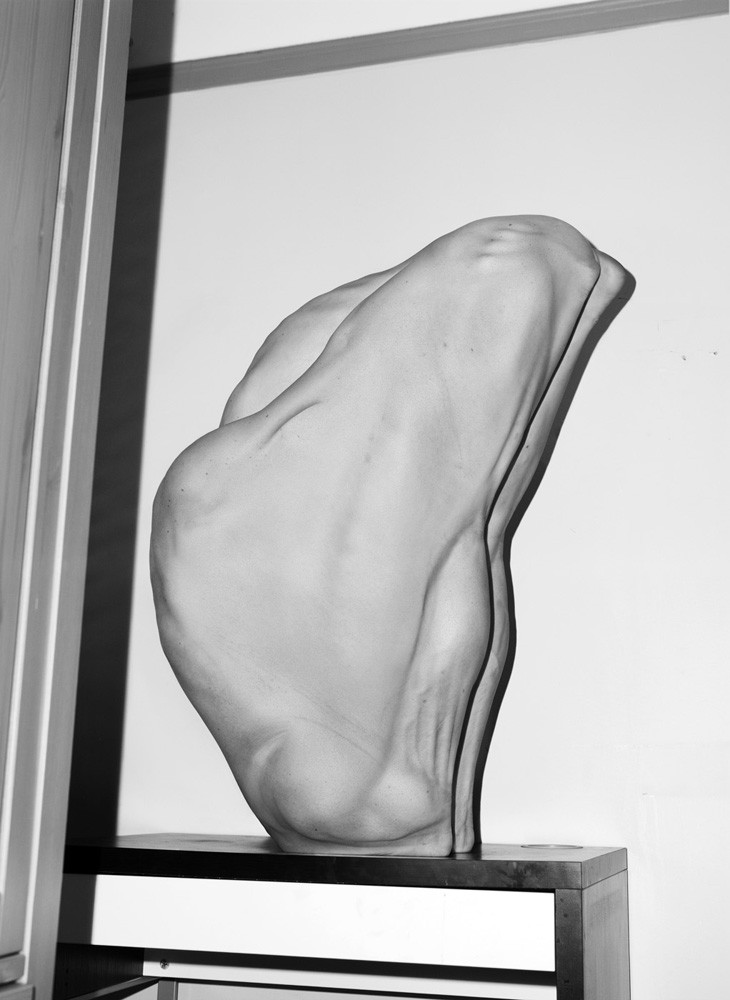

We went on to discuss his widely-acclaimed series Hester, which appears at first to be installation shots of sculptures rather than photographic works in themselves. Combining photos of multiple models per image, Asger molds the signifiers of the body, rendering intimate interior curvatures or functional musculature irrelevant. The result is a rich textural play of light on flesh, creating an unsettling oscillation within the viewer between attraction and revulsion. I particularly love that some of the most beautiful details of the images, at least for me, are found in things like stretch marks and cellulite. I asked him if working with bodies in this way has changed how he views beauty. He said no, but only because he’s never particularly prescribed to conventional understandings of beauty.

AC: I don’t think it’s very interesting to see how people can use Photoshop or post production to, you know – I mean, that is why Photoshop was invented, it was invented to enhance people. To cater to a commercial industry that wanted to do something with images that you weren’t able to do in a traditional darkroom process, or at least not that easily.

diga.rt: I noticed that you’ve continued to do some commercial work, like portraits and some fashion stuff, and I’m curious how developing this distinct aesthetic has changed that relationship.

AC: Prior to doing this work I was pretty active as a commercial photographer. So when I started doing this work I pretty much lost that. It’s not advisable, but that’s kinda what I did. So that’s fine, I had to deal with that, but I was stubborn enough to keep doing my thing, because that’s what I wanted to do.

But over time, there’s been, especially magazines, that have been interested in commissioning me to do stuff. And you know, I can only take so many commissions because it’s time consuming. But I do it sometimes if it’s a cool project. And I’m also trying to make a living, and selling artworks is not a steady income, so, you have multiple ways of paying bills. But maybe it’s a way I can test some ideas, at least that’s how I see it.

diga.rt: What do you see happening next?

AC: I’m working on a show right now that’s going to be some drawings, mixed with photographs and some sculptures. I don’t know, I’m kind of in a state where I’m trying to explore other ways of doing this idea. And I really think it’s an idea, rather than something that’s confined to being just a photograph. So I’m curious to see how far I can go with that.

And then I have this book, which is also gonna be a couple shows, with this other photographer, his name is Roger Ballen (link no longer accessible).

diga.rt: Oh yeah, I’ve seen the work the two of you did for Vice. I was in Tokyo at the time and sort of stumbled across the show at the Diesel Gallery. I love his work. So you’ve continued that conversation?

AC: Thank you, yeah, so that’s going to be finalized in the next couple of months. And that’s sort of what’s in the works!

:::FIN:::