Eyeworks is an invitational festival focusing on abstract animation and unconventional character animation. Festival programs showcase outstanding experimental animation of all sorts, and include classic films and new works.

Co-curator and University of Richmond alumni Alexander Stewart sat down with Digital America to talk about the genesis of the Eyeworks festival, along with the process of curating the festival with his co-director Lilli Carré.

:::

DigA: As a starting point for your curatorial practice how did Eyeworks come to be the much anticipated festival that is, and has always had the same curatorial purpose, or has it developed since you first began?

AS: Lilli and I started doing Eyeworks in 2010. We felt like there was a space for a way of thinking about animation that we were both interested in that we didn’t necessarily feel was very visible. We were both interested in animation in our own practices, but any time we would go to animation screenings or animation festivals we always felt, “This is not quite what I like about animation.” A lot of festival animation programs have a reliance on humor and narrative, and a certain tradition of character performance, or else a type of film where things are very metaphoric, or socially conscious in a certain way that feels a little simplistic. There’s this range of stuff that you normally see in animation screenings that we both felt a little bit frustrated by. We both are people who love making animation and are very interested in the idea of animating, and it just felt like we weren’t finding the stuff that we wanted to see presented together in a coherent way.

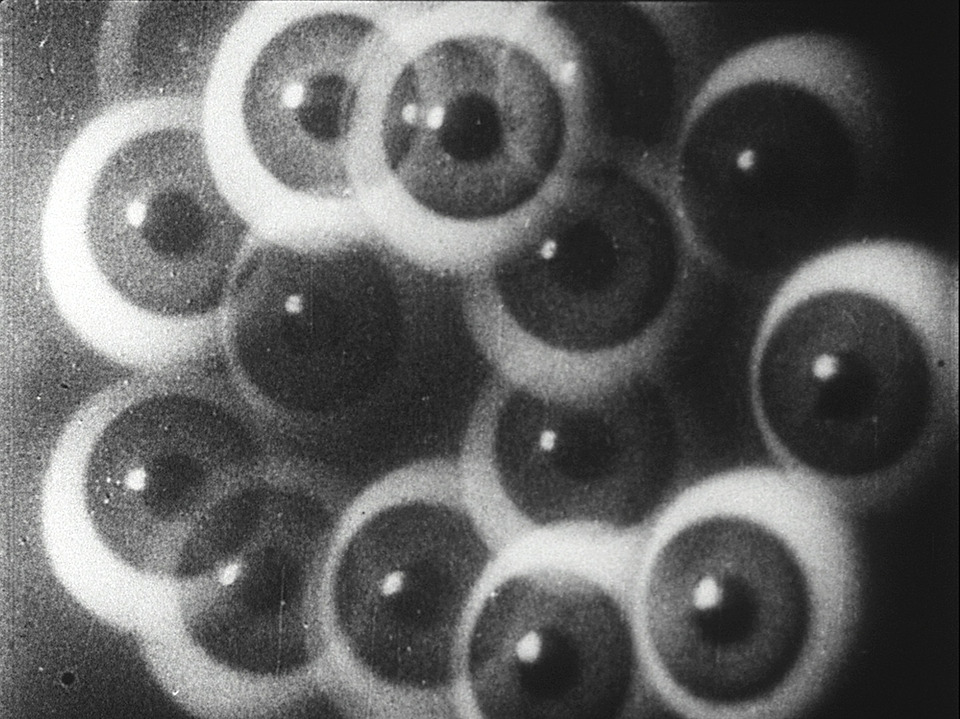

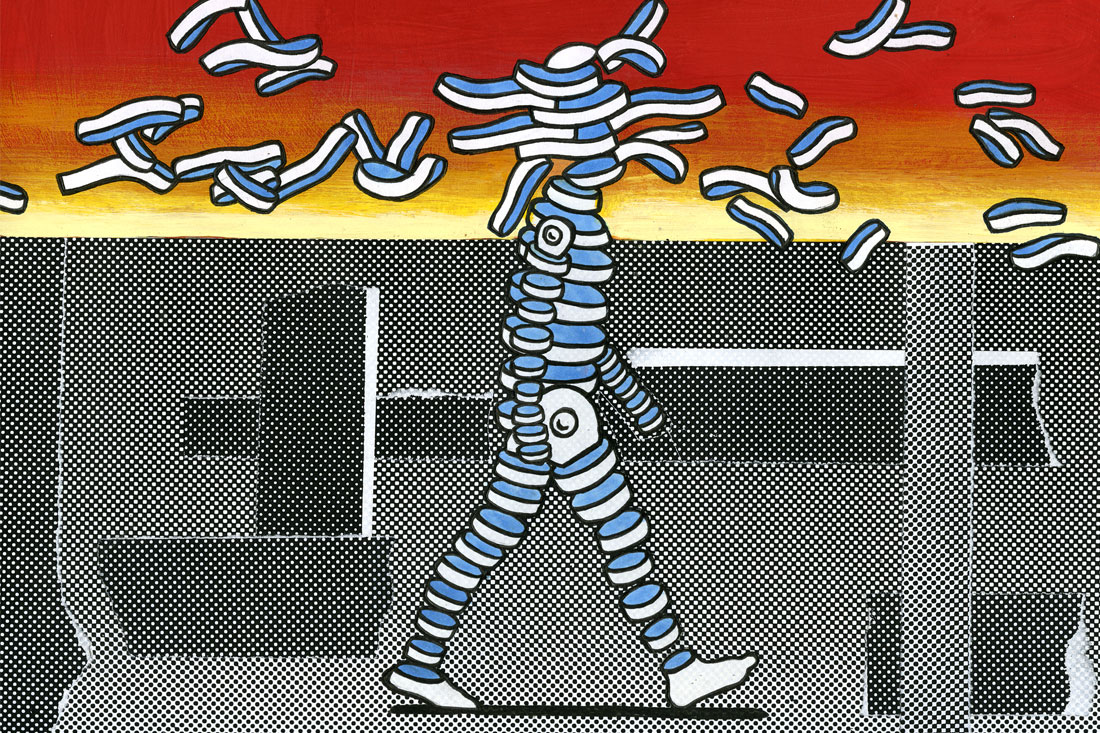

So we sort of thought of what we were interested in as this spectrum between avant-garde film and character animation and tried to work between these two poles. The term “character animation” refers to creating a figure that functions like a character on screen that has wants and desires and hopes and dreams and that we as the audience can identify with, or project onto them in a traditional cinematic way. Then there is the avant-garde model of cinema where you’re very conscious of a structural and material approach to working with time, or image, or color, or the frame, or a pure “film as film” kind of idea. An example of this idea of animation is the work of Paul Sharits, or even earlier visual-music people like Oskar Fishinger. There’s a purity, and a kind of simplicity, and rigor, and a focus of that work that we were interested in. We didn’t want to do a festival that was all experimental works. What we were interested in were people like Robert Breer, who was a really important experimental film person who made work that was both experimental and cartoony. We were also interested in people like Sally Cruikshank, who made cartoons that function like character animations, but they’re just really following their own logic, and they don’t feel like they’re beholden to the logic of much outside of a very bizarre version of Fleischer films or something. I think we were trying to figure out those two poles, on one hand a kind of unusual character animation, on the other a kind of abstract film that’s animated, and then to fill in between them with the kind of stuff we wanted to see.

The impetus at the beginning was that we didn’t see what we wanted to see happening. I think having done a lot more research now, there are some examples of people who have put together types of films we’re interested in, but we just weren’t around them or exposed to them or couldn’t access them. But, it’s sometimes it’s just the thought of, “we don’t see this thing, let’s do it” that gets you started.

We both at the time were living in Chicago, and Chicago has a healthy experimental film community and a really great DIY ethos in the art and music scenes. Lilli has a background in comics and the comics world, and especially in Chicago, if you want it to exist, you do it. You don’t wait for permission. I think it was really coming out of that Chicago, can-do, DIY vibe that we said, “Yeah, we’ll just do some screenings, it will be great”. At the time I was teaching at DePaul University, so I just booked the main theater and said, “We’re going to do a film festival, we’re going to do some screenings.” We got a bunch of films from this place in Chicago called Chicago Filmmakers that has a really intersting 16mm print collection. That was a big source of inspiration for us at the start, diving into their film collection from the 60s and 70s and 80s and 90s and learning about a lot of filmmakers that we just didn’t know. We would just go there and look and say, “OK, let’s just look at the catalog and find some films”. Right away we were trying to bring in the historical stuff and also encourage ourselves to learn more about it, and then to show it. The whole idea was to do a festival because we want this type of festival to exist, so let’s make it happen. We brought in a lot of contemporary work and a lot of older stuff, and then we had David O’Reilly come as our guest. Right from the start we thought, “Let’s have a guest, that really focuses the energy, to have someone in person.”

So that’s how we got the ball rolling. It was just really fun to do it, and to do the artwork and to plan it. Curating can be really satisfying. You work very hard on putting something together, and then you have this great moment where you have 150 or 200 people there to see it, with people standing in the back of that theater and sitting on the floor. After that happened, we said, “Well, this is fun, and people seem to like it, so let’s keep going with it, and keep doing it as long as it’s fun”. We are both also practicing artists, and I’m a teacher and Lilli does a lot of other work too. So we try to fit it in around our other stuff, and make sure it’s still enjoyable for us to do. This is the eighth year we’ve been doing it.

And to answer the second part your question, about how it’s changed, it absolutely has changed. I look back at the first year, the second year, the third year, and it’s not the same stuff I would program now. A lot of it is that my taste has changed and that Lilli’s taste has changed, and our tastes have changed together too. I think we show work now that is more challenging than we did when we started. We definitely show a lot more CG [computer graphics] work and digital work now. I think we showed a lot more drawn animation when we first started, very experimental work, but we were less interested in computer animation when we were starting to do the festival. Although, David OReilly was a CG artist, and the reason we brought him the first year is because we didn’t want the festival to be stuck in the past. We didn’t want to do something that was fetishizing the 70’s. There’s an influential book called Experimental Animation by Robert Russett and Cecile Starr, and Lilli and I are both very influenced that book, but we didn’t want to make a festival that’s just trying to figure out how to remind people that this book is great. In terms of how our taste has changed, I would say that it’s maybe become more focused on, in terms of technique, a lot more digital work and maybe a slightly looser definition of animation; not being afraid to drop the question of what is and isn’t animated, to get a little bit looser with that. I think we both have tried to push each other to be rigorous, to include work that feels rigorous and substantial that is animated, alongside work that feels playful and goofy that’s animated.

I think you want an art form to be able to ask a full range of questions about the experience of being alive today. As an artist, I want to say about animation as a medium, “I can ask all the questions that life asks of me. I don’t just have to treat animation as this kind of weird, reductive thing focused on jokes. I can do a broad range of thinking in the medium.” I think that’s the kind of the work that we felt was important to show, that it can contain all this stuff. It’s not like we’re not interested in fun, or we’re not interested in jokes. There’s a huge part of the history of animation. We want to have it there, but we also want to have work that feels formal and pure and intense. We want to have work that feels personal and expressive and intimate. We want to have work that feels political and social. We don’t necessarily want to go in any one direction, but we do want to make a case for the larger potential of the medium.

DigA: Individuals experience sound, video, and animation through a variety of platforms these days. From the big screen to computers, to iPhones, which affects their perception of the work. How does your specific presentation of Eyeworks change these perceptions?

AS: I think what we’re doing is all about cinematic consumption, or consuming something in a cinematic space, which can be in some ways a little old-fashioned. There’s a way to think about “the cinema” where it seems a little bit didactic or fascist. You have to come in and sit down in the seat and watch what we’re showing you in the order that we’re showing it to you, which feels a little bit contrarian in the sense that now so many things are based on the whims, or the demands, or the desires that I as a viewer have. I can start or stop something on my phone, and I can look at it wherever I want. I don’t have to pay attention to it any longer than I want to. And I can do like three things at once. But in a cinema, it’s sort of insisting on a slightly older model of attention span and a willingness to participate in something.

At the same time, we’re interested in the idea from avant-garde cinema of not giving people the totally immersive experience that entertainment cinema tends to present. The idea is that you go see the new Blade Runner movie and suddenly you’re washed over with this intense story, which I love, I love going to the movies that way too. But Eyeworks is a little bit of a different space. You come for this hour and ten minutes, hour and five minutes, to sit and contemplate this stuff that doesn’t necessarily have easy answers or doesn’t really make sense right off the bat. There’s a lot to look at, a lot to think about, but it isn’t totally immersive. I think in some ways that seems to be the optimal way to look at this kind of work, because a lot of it is very opaque. We don’t program a lot of work that has much language in it. Usually only one or two films will have talking or text in them, and a lot of the stuff is very non-linguistic. And you need that sort of work to be presented in a way that allows for contemplation and digestion. I just know my own personal experience, trying to look at films and think about showing them. If I’m on my computer, and I’m trying to look at something, I have to be really committed to sit down, fullscreen it, and don’t look around at other stuff on the internet while I’m doing it. You have to pay attention to this kind of work, you know? I think the cinema feels like the best way to do that. Limiting distraction, and just letting people sit and be in the same room at the same time, with the work at a larger scale.

I’m interested in the potential of streaming. I don’t know how that would work, but having seen some experimental short work recently coming up on streaming services like Kanopy and FilmStruck, I would be interested in seeing the possibilities of trying to show this work in that context too. But I just want to also be protective of it, because you want the image quality to be as good as you can get it, and you want the viewing experience to be as unencumbered as possible to give the work the space that it needs.

DigA: Along those same lines, can you talk about utilizing 16mm films in your screenings?

AS: From the very beginning, we showed a lot of 16mm at Eyeworks, and part of it was because what I studied when I was in grad school was a lot of experimental and avant-garde film, and that was the stuff that I was super into at the time. A lot of the history of experimental film is 16mm, because that’s historically sort of the artist’s medium. It’s not as expensive as 35mm, but you can still project it on a big screen. The history of 16mm film was really fascinating to me and it was influential on me as an artist. That medium has a scale of cinema where you could have a screening for six people in your house, or you could show it in a theater for 100 people. We were interested in the lineage of 16mm as an artist’s medium and the lineage of it is coming from experimental film and also touring film programs in the 60s, 70s, 80s, as a portable format. So if you were doing a film tour you could bring a 16mm projector with you, a tabletop projector you could set up anywhere, versus a big dedicated theater projector. That scale of the medium seemed really important to us. It’s a format that feels much more like personal filmmaking too, and I think that was always an important thing to us. Almost all of the films we show are made with the model of one maker, one film. We’re not really as interested in the model of studio production. We do show some films that are made by studios and teams, but we’re more interested in the vision, the quirkiness, the personality, the individuality, the craft, of one person’s relationship to material coming through in the films. And 16mm feels like it’s the history of that kind of filmmaking, that’s the format for it. So it felt important to us to try to show as much on 16mm as possible. It looks different, it feels different and has a different presence from digital images. But, it’s harder and harder to find places that can show it properly. There’s theaters like the Block Cinema in Chicago, which has great projectionists and nice projectors and the 16mm always looks great. There’s places like the Grace Street Theater here in Richmond that can show it well. To be able to work with a place that’s interested in supporting 16mm is really important to us because fewer and fewer people know how to do it, and it can look bad if you’re not careful. But, it can also look brilliant. It can look so good. Sometimes if you see a new print and you see it on a nice projector in a nice theater you’re like, “wow”, it just pops. I think we want to show 16 as much as we can, but we want it to be shown optimally. We’re both interested in the history of that as a format medium and the experience of actually sitting in theater watching a print. It’s magical in its own way. We’ve shown 35mm for a couple of films through the years, but that hasn’t been as sustainable because we can’t tour with it in the same way. And in comparison to 16mm, there’s not a lot of artists who do what we’re interested in who were able to make work on 35mm.

DigA: I’m curious about your role as both an artist and curator. I’m wondering if you see that switching of hats as being an extension of your work and your personal practice, and how you feel like your own exploration of animation and time-based media.

AS: Well, specifically about wearing two hats, from the very beginning we said, rule number one is show great work that we really want to show. Rule number two is, we’re never going to show our own work. It’s a clear line for us. It can feel self-serving, or even lazy, to curate yourself into your programs. It makes sense that someone who is both an artist and a curator would be interested in certain ideas in other people’s work, because it relates to their own practice, and then want to put their work in context of other people’s work, but we really didn’t want to do that. It’s about the work that we see as exciting, it’s not about us in the work. And yes, it does all feed back into our work. We feed ourselves with the stuff we show. But the delineation is important to us, to not mix it. I make animation, Lilli makes animation, and I think we both feel like we are doing some of the same kind of thinking that we would be doing in our work through curatorial stuff, where we are processing or probing or examining or mulling over certain thoughts. At this point, I’ve shown the Eyeworks program that we showed yesterday four times now, I sat in a theater for that same program four times all the way through, plus all the times we discussed pieces and plus all the times we looked at them beforehand. You really get to know that work, and you really get to know it intimately. Watching all the films together, there’s a processing of ideas in the same way that happens if you’re trying to figure something out for your own work. As a teacher that happens to me too, where I feel like I come up with a class topic or a theme or something that I’ve been thinking about, and by using certain texts and discussions or projects, there ends up being a similar kind of processing of those ideas in the classroom, outside of my art practice, but that relates to the ideas that I’m interested in my art practice. It took me a while to realize that teaching is also part of the same continuum of processing culture that I’m interested in as an artist and a curator, with ideas and things that I’m thinking about.

DigA: Is there any particular works in this year’s program that you would consider your favorite? Anything that you could talk about forever?

AS: One is a film by Annapurna Kumar that’s called Mountain Castle Mountain Flower Plastic. She was a student at CalArts last year and just finished her MFA, and before that she went to VCU here in Richmond. She’s a really interesting thinker and the work is so dense. Working with her a little bit as she made it and watching her process those ideas, I have a huge amount of respect for her practice and the way she puts ideas together. Every time I look at the film I see more in it. It’s got this really nice balance of ingredients. That’s a film that I could watch over and over again for sure.

There’s a film called Soft Body Goal by Jaakko Pallasvuo. That one has this great line in it where he says, “Every art student today is doing bad CG, what’s so special about what I’m doing?” That feels like a really timely joke, considering how much that is happening in the art world. It’s not just about him making a dig, it’s also the way he’s questioning the relevance of doing anything at all. The film is all about CG bodies. That’s a thing Lilli and I have been really interested in recently. Lilli especially, since she really gets into this in her work too, the idea of cartoon bodies and the malleability of bodies, and the cartoon body onscreen that’s both a depiction of a body, but also a character that can’t possibly die. I think he gets into some of that in his film. Every time it comes on in the program, it just hits perfectly.

In the second program there’s two films that I really can watch repeatedly. One is the Barbara Hammer film No No Nooky T.V., which is an early Amiga animation that she made in 1987 that is just unrelenting. It feels so contemporary, 30 years later. It’s so similar to the way that people make stories and videos on Instagram with little pieces of text and writing over images. There’s an immediacy of the image and a flatness of the image in her movie. It feels like it’s speaking to an image form of now, in this contemporary way. I love the intensity of that film; it’s not overly processed. It feels like she has a thought and it goes on the screen. There’s a spontaneity to it that I love. You don’t see that kind of intensity in a lot of animation, that kind of unfiltered erotic content and that directness. That’s a great film.

The last one that I’ll mention that I really love in that program is the film Dry Standpipe by Wojciech Bąkowski. He has been making fascinating animation work for a while, but this is the first piece of his we’ve shown. The film has a dry Eastern European sensibility, and is kind of bleak, but also poetic and beautiful in unexpected ways. He uses these self-referential moves that tie it together. It felt like Dry Standpipe and No No Nooky T.V. were the two films most people were talking about after the screenings this year. I think they’re both [Hammer and Bąkowski] really wonderful, in different ways. And they can be challenging. Those are two real favorites in that second program.

:::

About Eyeworks:

Eyeworks concentrates on works made by individual artists, drawing on the lineage of avant-garde cinema as well as the tradition of classic character animation and cartooning. The aim of Eyeworks is to present works that engage the enormous potential inherent in the art form of animation.

The Eyeworks Festival of Experimental Animation was founded in 2010, and is based in Los Angeles. David OReilly, Lori Damiano, Nancy Andrews, Caleb Wood, Takeshi Murata, Martin Arnold, and Jacolby Satterwhite have been featured as festival guests. In addition to its annual fall festival, Eyeworks has presented screenings in Sweden, Finland, France, Poland, and Croatia; at the Drawing Center in New York and the MCA in Chicago; as part of the Animation Block Party, Brooklyn Comics & Graphics Festival, and the Chicago Alternative Comics Expo; and at CalArts, Virginia Commonwealth University, and at Dartmouth College.

About the artist:

Alexander Stewart (1981, Mobile, Alabama) received his MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His short films have screened internationally, including at the International Film Festival Rotterdam, the Ottawa International Animation Festival, the Ann Arbor Film Festival, and Image Forum in Japan. He is co-founder of the Eyeworks Festival of Experimental Animation, and curated the film and video screening series at Roots & Culture Contemporary Art Center in Chicago from 2006 to 2013. He lives in Los Angeles and teaches in the Experimental Animation program at CalArts.

Alexander Stewart (1981, Mobile, Alabama) received his MFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. His short films have screened internationally, including at the International Film Festival Rotterdam, the Ottawa International Animation Festival, the Ann Arbor Film Festival, and Image Forum in Japan. He is co-founder of the Eyeworks Festival of Experimental Animation, and curated the film and video screening series at Roots & Culture Contemporary Art Center in Chicago from 2006 to 2013. He lives in Los Angeles and teaches in the Experimental Animation program at CalArts.