Molly O’Donnell’s Spit was published in Issue 12 of Digital America. O’Donnell talked with Digital America about Spit and her other work in Potpourri and Default. O’Donnell delves into the world of ASMR as she discusses the way in which her work in general tackles the topics of gender, sexuality, and identity in context of today’s internet culture.

DigA: Spit provokes plenty of physical and emotional responses – namely a gag reflex – yet, it’s difficult to look away. What drives you to explore imagery that commands such a visceral response from your viewer? What is your process as you create and capture these moments?

MO: I love the terminology of gag reflex, it reflects my most recent series Default perfectly! That is if your indeed squeamish, I myself am not, if you can’t already tell. This revolting yet hypnotizing reaction seems almost necessary considering how it so clearly depicts the internet and the role we play in its tantalizing façade.

While creating this series I had to suck myself down the internet’s wormhole, because that’s sooo hard to do. It was more like bringing my Instagram archive in for critique and watching my professor’s face completely befuddled as I explained what ASMR was, meanwhile hoping she wasn’t going to fail me. My inspiration board consists mostly of teenage slime videos, darkweb mystery box unboxing videos, Mukbang videos, HowToBasic videos, Finsta accounts, soap shaving videos, videos of veterans surprising their dogs, and of course ASMR (Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response).

It is these trends, or rather subcultures of the internet, that play an intricate part in my fascination with internet euphoria and how equally vulnerable and powerful we feel when we present ourselves online. ASMR in particular was a huge inspiration for my work by imagining YouTube as a playground for these voices and characters to communicate and elicit these sensory reactions–all for strangers behind a screen.

DigA: You’re intrigued, if not inspired by, YouTube’s ASMR (Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response), do you feel that your video work, in particular Spit, aims to evoke similar feelings of unsolicited sexual intimacy from video to viewer?

MO: Absolutely, except I don’t know if I’d describe its nature as unsolicited. For me this relationship between ourselves and this virtual persona is not only consensual but extremely desired. It’s funny to think about having made Spit prior to my examination of ASMR considering it visually accomplishes what ASMR aims to satisfy audibly.

Spit triggers in our brain as a sexual encounter even though there is no actual physical contact. This video actually got removed from Instagram awhile ago when I had first created it. I can only imagine that the ambiguity of the source of the liquid triggered Instagram’s semen algorithm or something, not the first time this has happened and certainly not the last.

The relationship in Spit is nurturing and almost dependent on one another for gratification. This idea of internet euphoria and immediate gratification quickly brought me to ASMR videos on YouTube. My first experience with ASMR was the inclination that I was watching PG roleplay porn due to its extreme intimate and attentive audio brought on by the performer (who is typically female identifying). It is truly a wild experience looking up ASMR and watching it for the first time. I wholeheartedly respect the community, and even more so after discovering my own anxiety relieving euphoria after falling asleep to a woman typing on a keyboard while chewing a pickle. Even so, I found these communities of internet culture like ASMR, or something even less intimate but equally gratifying like slime videos or unboxing videos, as a catalyst for this sensual yet complex intimacy that constitutes itself within our digital age.

DigA: You often get very close and personal with your subjects. For example, in your portfolio Default the focus is on noses, eyes, or mouths and it’s difficult to distinguish gender beyond the lens. Pairing this observation with the intentional intimacy of the work, how do you approach gender in these pieces specifically or in your work more broadly?

MO: I started fragmenting the body partly because I wanted gender fluidity, but also I needed my subject matter to be more cyborg than human. Simplifying a human to its senses creates an unsettling disembodiment with the viewer. The hydrogenous performer in the videos are recognizably human due to its tears, blood and saliva, but yet there is still this lack of identity and even lack of humanness through its disfigurement. It all clicked for me after reading Donna Haraway’s Cyborg Manifesto when I realized the tension in my work was not that I was erasing this gendered perspective but rather reinventing this female gaze by rejecting the boundaries established on what’s “feminine” and even more so on what it means to be “human”. Even the devices in the installation play a huge role in the delivery of the content. Apple, being the powerhouse of the cell of our modern age (meme reference), became just as much part of the series as the videos themselves.

When we broadcast ourselves online, we become nothing more than pixels with a soft voice. It’s like that Instagram influencer/robot Miquela, @lilmiquela, when realizing we live in a world where a hipster robot can have over one million followers who don’t give a damn that their infatuated with the idea of a literal robot who rocks Prada and advocates for Black Lives Matter. That can easily be a tangent for another time….

DigA: I’m intrigued by how your other portfolio work, for example Potpourri and Shedding, so strongly depict the intimate complexities of the naked female body. How did your artistic interest in the natural feminine body progress into the grotesque imagery of your work in Default?

MO: Potpourri began as a series of self-portraits exploring how my conception of gender had been structured within these domestic and often surreal like spaces of my home. While also eventually coming to terms with how my white female body carried its own set of privileges along with the pastel colored walls coated in my home. As the series progressed, it became less about this charged space and more about thinking critically through the lenses in which I was looking at my body.

At that time, I was using my iPhone as a remote using an app called Canon Connect, which allowed me to see through the eyes of my DLSR through the screen of my iPhone. Seeing my photographs appear on my smartphone before they reached my camera was not only challenging this hierarchy of the photographic medium, but also allowed me to see the iPhone as key collaborator in my work. It was an incredible moment for me when I realized my iPhone had more authority than my DLSR. This led to a side series of images from Potpourri with all the same imagery except my hand was revealed holding my iPhone with the Canon Connect app showing the camera’s live view on my phone. Sometimes I wonder if that would have created a stronger series, but why go down that road.

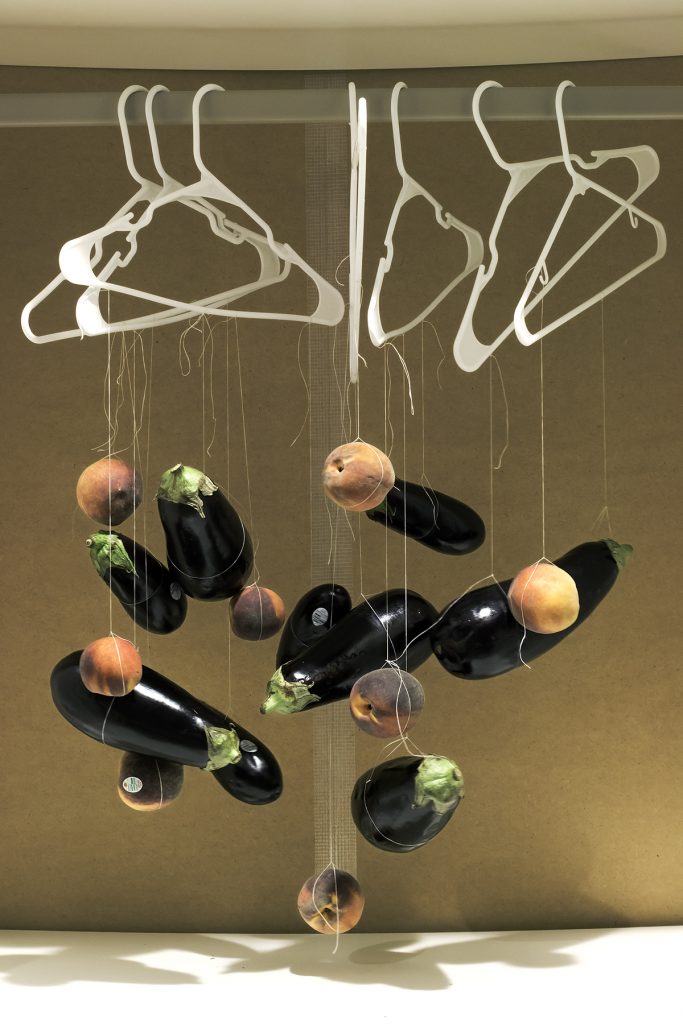

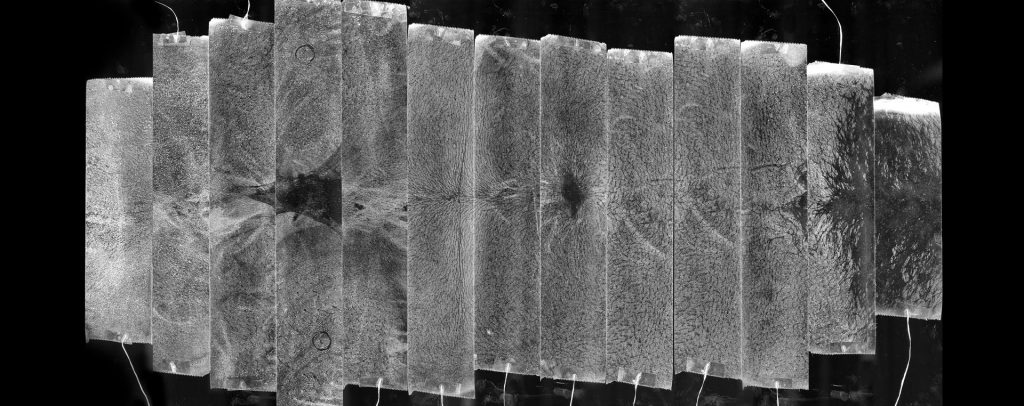

After that, I was completely engrossed in the politics of image objectification, censorship and representations of sexuality and gender on platforms like social media which evidently inspired my Default series. You can even see a tone shift in Potpourri in the image Sexting, where I was moving away from the hyper feminine and masculine representations in the domestic space and looking more critically at how we communicate and express our desires online by simply objectifying two innocent and ironically shaped household foods, an eggplant and a peach.

DigA: Your work questions the portrayal of the contemporary female gaze, which is a topic that we’ve published quite a bit on over the years, particularly how women are ‘meant’ to express their sexuality and bodies through the lens of media and the internet, for example in Blonde Women Looking Away by Szilvia Ruszev. Can you talk about how you work with the stigma of female sexuality within our contemporary culture? What larger conversation do you hope to incite or contribute to?

MO: That’s a very good question that most definitely gave me a chill of anxiety, but now that I’ve taken some CBD I can try to take a whack at it.

My work has been continuously interested in what it means today to be a woman in 2018, in this digital age of self-creation. Things like Finstagram (Fake-Instagram) have been an inspiring tool for me, looking at how as a digital culture we have all these megaphones on social media, yet we are still desiring a more private and intimate setting to challenge our online public persona. If you don’t know what a Finsta is I suggest looking it up the definition on urban dictionary for a good chuckle.

Although, at times it feels truly like a 21st century me problem; white cis woman complains about getting removed from Instagram or white cis woman smashes iPhone to dismantle the patriarchy. But in reality, these are the conversations that are happening online and the internet has become an endless tool for activists of all gender identities to reclaim their visibility from the judgmental trolls of our society. And I find it even more beautiful that this is done alongside all muckiness of the internet. Even the term female gaze is starting to feel weird to say since every notion of what it means to be female and male is completely fluid and beautifully diverse. This isn’t to say new wave feminism is not valid and the female gaze isn’t a prominent key factor in contemporary art right now. I am interested in seeing artists push those boundaries and redefine how gender is seen through not just the female gaze but the gaze of the MacBook owner chillen on their bed binge watching Broad City.

These multifaceted perspectives that contribute to this conversation of the female gaze are continually in flux and are constantly influenced by these internet modalities that occupy our day to day. My work attempts to not only challenge its histories and problems but also celebrate the female gaze for all its raw, unabashed, and radical rage.