PINK FLOYD

THE ENDLESS RIVER (2014)

CAPITOL RECORDS

Pink Floyd is haunted.

Haunted first by the ghost of Syd Barrett, co-founder and lead architect of the group’s first record, The Piper at the Gates of Dawn (1967), described by Peter Bebergal, author of Season of the Witch: How the Occult Saved Rock and Roll, as “representative of all the different spiritual ideas that people were interested in…Eastern mysticism, cosmic consciousness… romantic idealization of the pagan past.” The wild and brilliant pop-songwriter of tracks featuring gnomes, witches, and black cats named Lucifer Sam, became seemingly lost in a combination of hallucinogens, schizophrenia, and stardom.

Later, the band became haunted by the megalomania of Roger Waters who kicked out a member while captaining the group’s rise to incredible excess. And now, with the final Pink Floyd record, it is the deceased co-founder, Richard Wright, who haunts the band. The history of Pink Floyd is one of constant exorcism. With the release of The Endless River (TER), a tribute to the unsung importance of keyboardist, Wright, the group, consisting of David Gilmour and Nick Mason, continues its long journey for redemption, and settling of old scores –though the group promises this is their last, their epitaph.

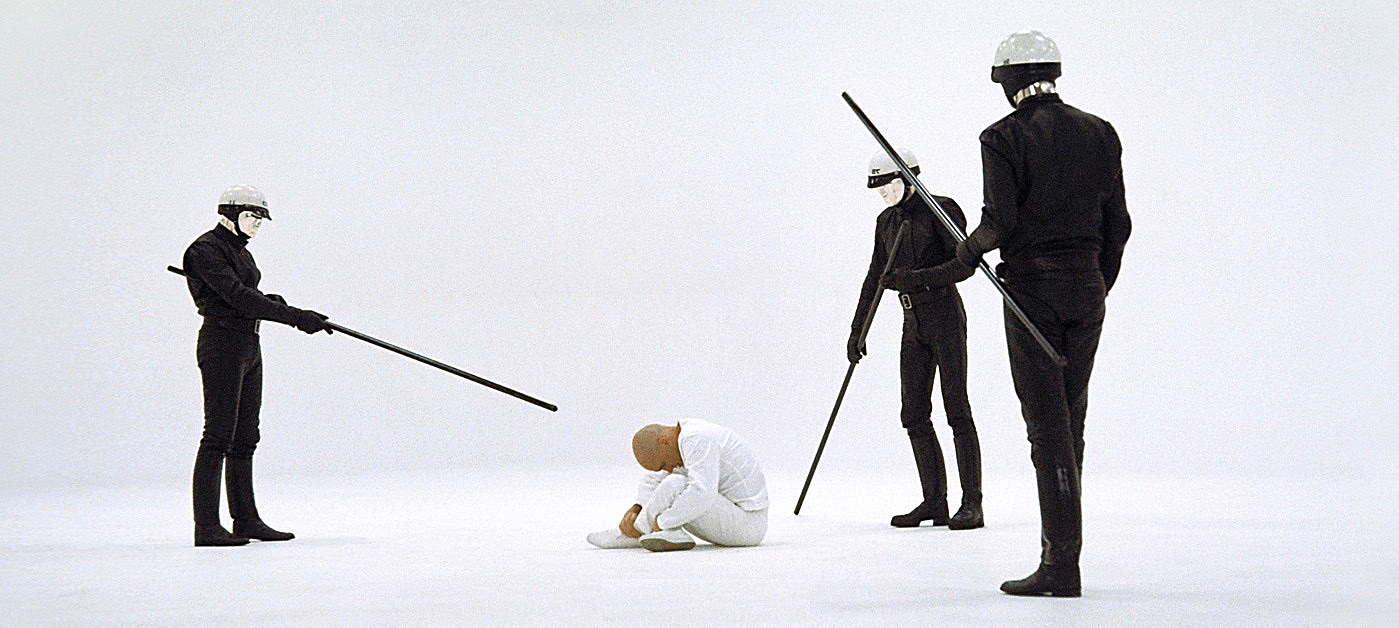

It has never been easier to wake the dead. Today the ghosts of 2-Pac and Michael Jackson perform live to an audience using old and new tracks, or CGI magic sometimes compels the dead to rise once more for their role in The Hunger Games. The question of the persistence of one’s image and contractual obligations, posthumously, is something to ponder. But besides the legal ramifications regarding ownership, ghosts tend to confuse both fans and critics, who equate authenticity with newness. Writing for Consequence of Sound, critic Cap Blackard calls the new Pink Floyd record “the world’s most lavishly appointed collection of outtakes.” It is true that TER features unreleased tracks recorded during the Division Bell (1994) sessions, which were then re-edited, and overdubbed to create this final installment. Critics struggle to accept the “oldness” of the sessions being revived as “new” products, as they are tunes recorded by ghosts, both living and dead. But the recording process is always about capturing a moment in time, and then often the manipulation of said audio, with multi-tracking, mixing, and re-mixing. It is always about presence and biased documentary. In the case of Jackson’s recent posthumous releases, the mystery of the author’s original intent is clouded by the final production. But, for Pink Floyd, members of whom still live, the band is known for in-studio experimentation. Time and space have always been source material.

Though ten years in the making, the lengthy, mostly instrumental record opens with a three part side featuring familiar Floydianisms: comforting organ sounds, and potent, lush guitar work reminiscent of the best instrumental moments found in Wish You Were Here (1975), a record where the keyboard work of Wright shines, in particular. It is admirable of Gilmour and drummer Mason, that TER calmly, meanders throughout its various parts, acting as vignettes to some larger story, one told without the element of lyrics and conceptualism, so largely important to the most successful tracks of the band’s repertoire (“Another Brick in the Wall,” “Time,” “Wish You Were Here”). Instead, the album, which starts off cautiously, begins to crescendo on side two, as “Sum” picks up the pace with a more frenetic synth, and wailing guitar, leading to the tribal, percussion heavy “Skins.” From that point on, we have the entire range of TER, which, in the end represents the band’s most ambient work –one that consciously revels in the spiritual –while remaining, a masterful work of “jams,” short and to the point.

The album cover, arguably Floyd’s weakest, in its overly spiritual, cliché imagery, features a figure rowing away from the viewer; on a sea of clouds he travels towards the sun. It is unclear whether it is rising or setting. There is something awkward about the image in its directness. The weakness of the album cover is especially strange coming from Pink Floyd, a band who helped define the artistic potential of album art, in collaboration with the recently deceased designer Storm Thorgerson. However, the easy, religiosity of the scene is saved in some ways exactly because of its blatant, kitschy storytelling. Never before has the band entered so deeply into the aesthetic realm of new age. One could almost picture a mustachioed Yanni, Christ-like and jovial, as the rower. Perhaps the miracle of TER is not the conjuring of Wright’s spirit, but rather, this return to a neo mystical, or spiritual foundation first expressed by Barrett so many years prior –a return to the poeticism, and space for contemplation that the later work of Waters, in his militant verboseness was incapable of giving his listeners (The Wall, Final Cut). Instead, on TER we have the brief, minimalistic open-space of “The Lost Art of Conversation,” and “On Noodle Street,” featuring drum and bass, calmly grooving along, while a restrained guitar, very quietly jams behind. Throughout the record, there is this back and forth, this seeking, and this great search is something Pink Floyd is no stranger to.

“Would you like to say something before you leave? / Perhaps you’d care to state exactly how you feel. / We say goodbye before we’ve said hello,” sings Richard Wright in “Summer ’68,” a deep cut, single from the largely forgotten Atom Heart Mother (1970). A magnificent carnavalesque pop song, reminiscent of the harmonies, and structural chaos of Brian Wilson’s Smile (1966), “Summer ‘68” remains one of the few songs penned chiefly by Wright, and one which showcases the musician’s versatility. Panned by most critics, and the members of Pink Floyd themselves, Atom Heart Mother, filled with grandiosity and defined largely by the first side’s “Atom Heart Mother Suite,” still found the group leaderless, wandering, and experimenting years after their chief songwriter and vocalist, Syd Barrett was effectively forced out of the band by apparent mental following the release and success of their debut.

From the moment of Barrett’s departure, Pink Floyd was more like The Pink Floyd Sound –leaderless, Wright, Waters, Gilmour (brought in to replace Barrett) and to a lesser extent, Mason, shared songwriting and vocal duties. The headless Pink Floyd sound resulted in arguably the best period of the group’s output: Atom Heart Mother, Meddle (1971), and Obscured by Clouds (1972). They labored on, producing wildly inventive soundscapes (“Echoes”) and playful pop songs (“Free Four,” featuring an incredibly restrained Waters). Listening to the discography, one gets the impression that the band members were running hard, and fast; running away from their mystic past, severing ties with psychedelic pop, and instead searching, and conjuring mostly large, drawn out gaudy constructions –inspirations to later prog-rockers, while mastering the concept album. They ran until they broke at The Wall (1979). Their innovation lay chiefly in realizing the potential of storytelling, or championing the album-as-art, rather, than a collection of one-shot singles.

Yet, Barrett was far from gone, as he made triumphant, haunting returns in chiefly the lyrics of The Dark Side of the Moon (“And if the band you’re in starts playing different tunes,”) and the magna-opus “Shine On You Crazy Diamond.” From then on, Waters effectively took the helm, turning his eye towards the gritty realism of Animals (1977), and the lengthy, lyrical excurses found in The Wall. It seems at that point, Barrett, who died in 2006, was already gone in 1979.

It is the previous, transitional and leaderless unit that haunts the Gilmour-led Floyd. Gilmour continues to exorcise his guilt for taking Barrett’s place; while going to great pains to portray himself as the lassaiz-faire member compared to Waters’ fascism and finally, making it his duty to give Wright his due. While TER largely explores instrumentalism again, it happens to be the only track featuring vocals (lyrics by Polly Samson), “Louder Than Words,” introduced at the climax that TER is at its weakest, and which ultimately fails the album at a time when the sudden vocal could add that final stamp of finality and dynamism the band seeks. Instead, Gilmour sings the worst lyrics of the band’s repertoire, “We bitch and we fight/ Diss each other on sight/ But this thing we do/ these times together / Rain or shine or stormy weather / this thing we do,” he goes on later in the chorus, “It’s louder than words.” The lyrics themselves are, like the album art, cliché and overly simplistic, while also being completely contradictory (where’s Waters in this tribute?) and once more self-serving to Gilmour’s status as the democratically minded Floydian.

At times The Endless River is powerfully nostalgic and romantic, while in other moments, it is weak in its self-reflexivity. In the end, it does not reach the level of critical expertise that David Bowie exhibits in The Next Day (2013), but it is “Autumn ‘68” (a seasonal continuation of “Summer ‘68”) that best conjures Wright, with its elegiac organ –both dark, brooding, spiritual and foreboding –a simple send off to a solid band mate that best represents the historical ghosts of Pink Floyd.

Norberto Gomez Jr. is a multi-media artist, curator and independent scholar based in Baltimore, Maryland. His research interests include popular and digital culture, and the intersection between technology and mysticism. He holds a PhD in Media, Art & Text from Virginia Commonwealth University (2013), and an MFA in painting and drawing from University of Houston (2009). www.norbertogomezjr.com & info@norbertogomezjr.com & you can follow him @theIKZ.