Digital America interviewed Ciarán Short in November 2022 about his piece American Re-Education (2022).

:::

Digital America: You created the video piece iHope (2021) in the midst of the Black Lives Matter protests. Here we are, almost two years later. How has your perspective of the BLM movement changed?

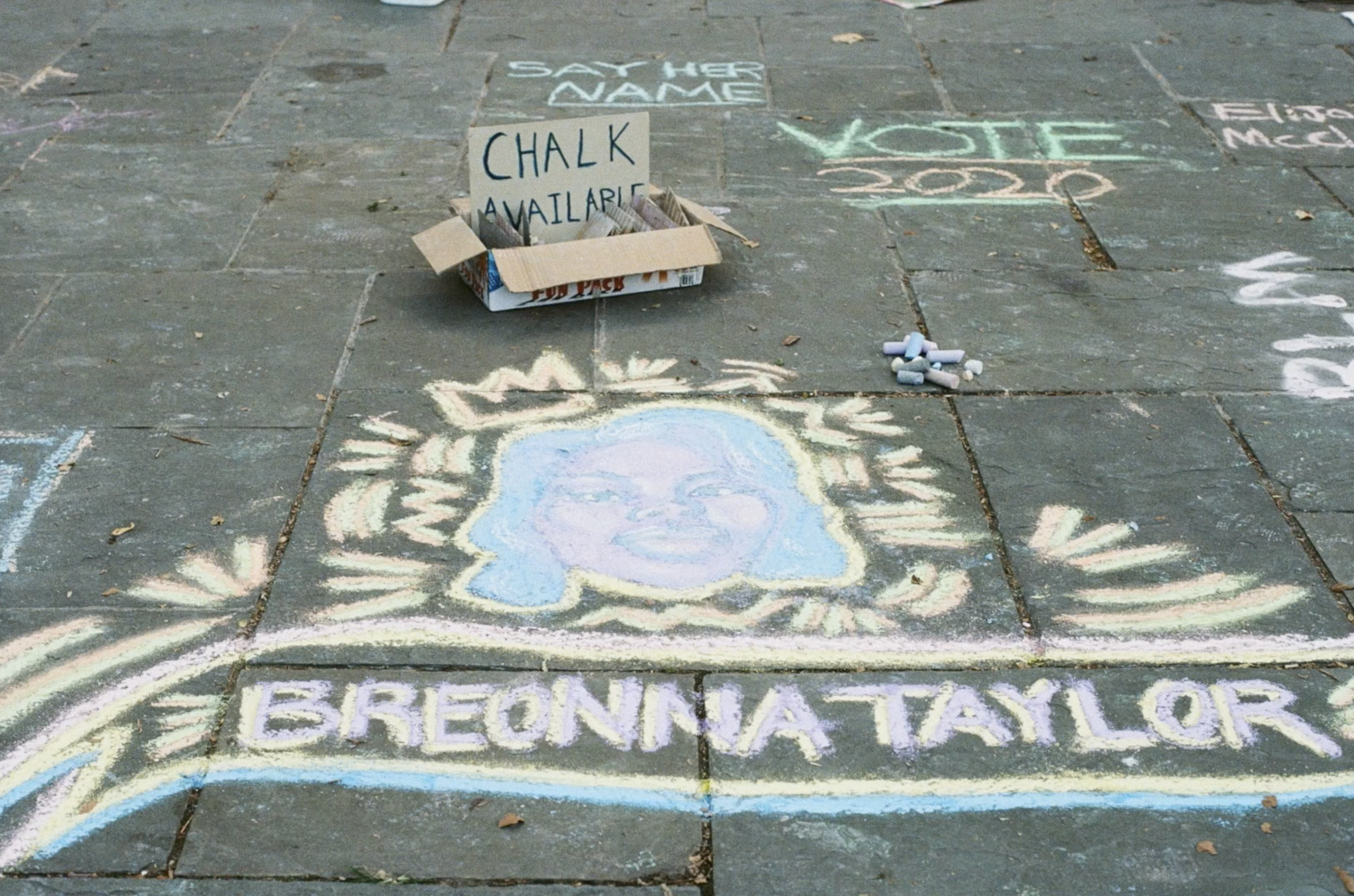

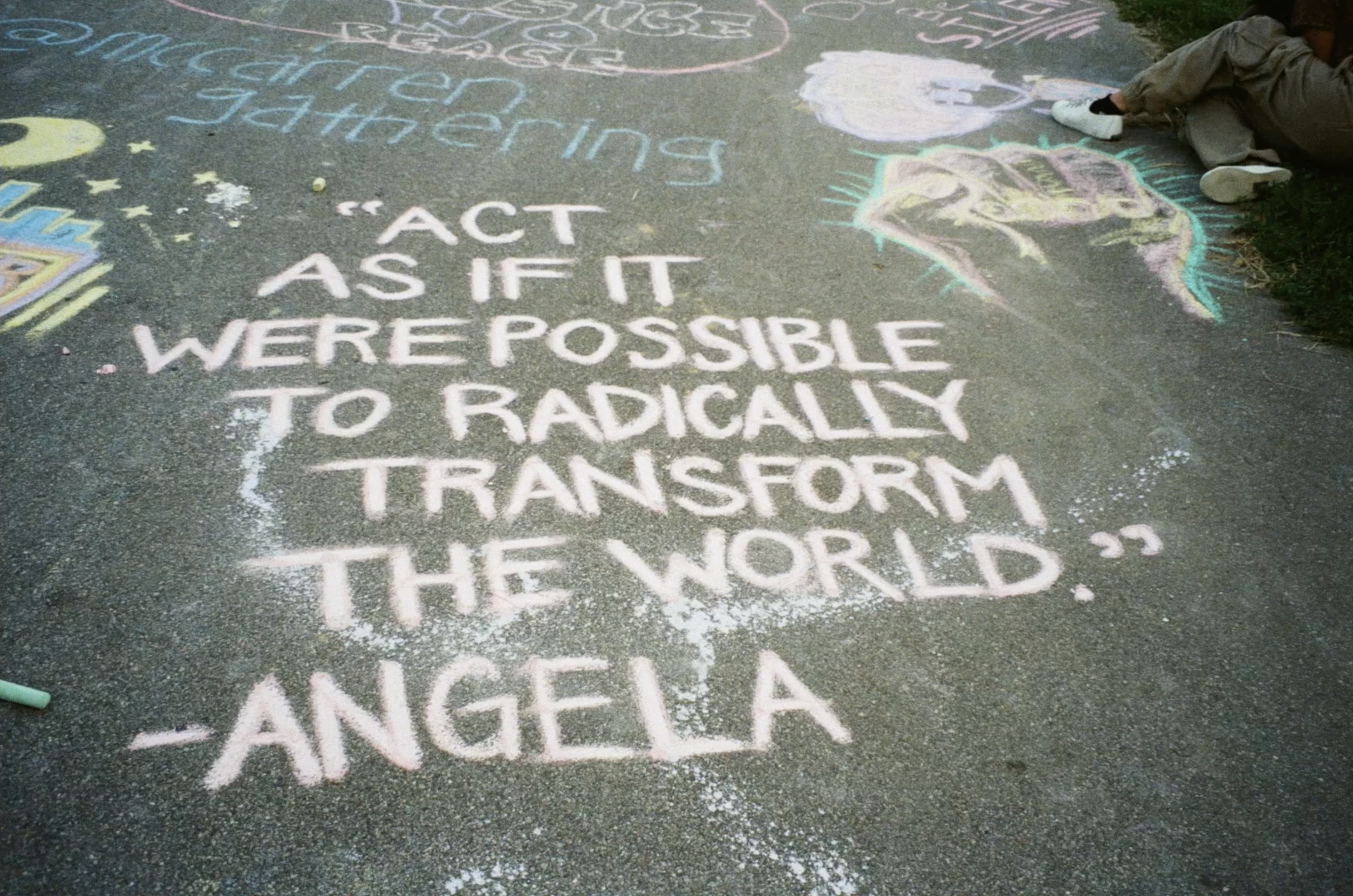

Cirián Short: During the height of the movement I was balancing a feeling of hope and pessimism that has definitely remained in flux over the past two years as current events and the social climate remain rather volatile. I do believe the movement made a significant impact on how people conduct themselves out of fear of being labeled as a racist or unsupportive of racial justice. While this shift is greatly performative, it does prompt people to think more deeply and take pause before making potentially rash decisions. However, on an internal level I think people predominantly still hold many of the same prejudices and associations that continue to further propel the subjugation of black people. My optimism remains in the voices of the many black people that gained a platform from their activism and continue to advocate for others. While many opportunities were generated by the hollow initiatives of corporate interest to capture the spending dollars of a more diverse audience, once in positions of influence activists have a greater likelihood to implement long lasting change. I believe the next couple of years will truly determine the success or failures of the BLM movement as I believe a five year wake following any social movement is needed to properly assess cultural impact.

Screenshot from Ciarán Short’s iHope (2021)

DigA: In iHope, an original poem narrates the video. Even though you wrote the questions, you choose to have a computer narrate the collection of crowdsourced reflections on American History instead of your own voice. What inspired this decision?

CS: I chose to have a computer narrate the audio in an attempt to mimic the detached nature in which the subjects answered the questions. Many of the respondents opted to remain anonymous and the hollow quality of the computer-generated voice felt mysterious and most cohesive with other components of the project. Having utilized an online form to collect responses I wanted the narration to be reminiscent of scouring an internet comments section or chatroom. Additionally, I intended to try and create a clear separation from my artistic voice and the featured responses. Although my choice in curation and the selection of the piece is evident, using the computer generated voice was a decision to situate the unknown respondents as mass collaborators contributing to a distinct part of the piece.

DigA: In your new work American Re-Education (2022), you immediately pull the audience in with the truth: “To have a sliding scale of privilege depending on your race, gender, class, sexual orientation, religion, birthplace, etc. It means to vote in elections, keep up with current events, and watch out for your neighbors.” Why did you choose to start your video off with the discussion of privilege and what it means? How do you think your American identity is shaped by these labels?

CS: I chose to open the video with that quote because similarly to how different people’s experience in America depends on privilege, so will one’s viewing and perspective on the piece. My American identity is informed by the various labels that are either placed on me or I actively identify with such as black, straight cisgender male, and New York City native. The media I consume, the art I make, the people I associate with, and all decisions I’ve made throughout my life have either been subconsciously or overtly influenced by these labels. I recognize that I have a great deal of privilege in various aspects in my life but am also less privileged than others with regards to race and socioeconomic class. Although the validity of some personal identifiers can be debated, prejudice does exist and greatly skews the perspectives of all people, whether intentional or not. I make art with the intention of challenging and subverting bias but obviously I have many blindspots which I think I come up against as I work through and research my new projects.

DigA: An important component of the BLM movement is fighting to include accurate African-American history in foundational history classes. In your new work American Re-Education (2022), you ask, “What’s a random fact you remember from your American history education?” What inspired you to ask this question of the audience? How do the answers perhaps shape the concept of American identity?

CS: This work was actually born out of a larger scale project I’m currently working on that’s centered on American History where I’ll be creating an original US History “textbook.” This textbook will be a reimagining of the US History curriculum, collaging archival texts and photos, as well as introducing new original text, interviews and photography related to the present day, particularly the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter Movement in the summer of 2020 and social movements within the past 100 years that have extensive media documentation. For this document, I will be conducting extensive research in looking through print archives of nationalist propaganda and educational literature, as well as local and national activist zines and newspapers printed during the 1960s and 1970s. Similarly to traditional history textbooks, I will spotlight certain historically significant individuals. These spotlights will both take aim at American heroes that have committed glaring atrocities and activist leaders spanning different eras that are rarely recognized on a wide scale. To invert the hegemonic formation of history being written by a small class of individuals and academics and disseminated to the masses, I will extensively employ first person accounts sourced from interviews with those directly impacted by the text’s content.

DigA: Throughout American Re-Education, you present specific questions to the viewer. Juxtaposed with these questions are distorted clips of popular American culture. What factors contributed to choosing the videos/images that visually correspond with the question?

CS: I had a couple of images and video clips in my mind as I set out to make the project and then went down an extensive hole, watching various YouTube videos and researching news archives. In the narrowing process, I downloaded a tremendous amount of content and then began looking for patterns or similarities across media. Once I became more familiar with my selected videos it was easy to recognize the moments of intersection where I could transition between clips and begin to create a story.

DigA: You say this piece is a story, how do you see the story ending? Now that you have received your masters degree, what are you planning on doing?

CS: In terms of the piece, I initially organized the work to end with leading into the present, however with the digital distortion resulting from the data moshing it muddied any potential linear narrative and I felt this accurately depicted the hectic nature of the ebb and flows of American History. For me the end of the story is uncertain and a reflection of the mystery that’s in store for American society.

This spring I opened up an alternative art gallery in the East Village called All Street NYC. Currently I’m working there full time curating visual art exhibitions and organizing community gatherings centered around art. We predominantly collaborate and show the work of underrepresented and emerging artists. In addition, I’ll be teaching a course at New York University this spring about the intersection of art and social movements and continuing my independent artistic practice.

:::

Check out iHope by Ciarán Short.

Check out American Re-Education by Ciarán Short.

:::

Ciarán Short is a multimedia artist and activist born and raised in NYC. His work explores New York culture and tackles issues of race and masculinity. He co-founded the All Street Journal, a protest group utilizing art to raise visibility and support the BLM movement and housing justice in NY. With this group, he organized protests across the city using the creation of art as a focus to build community and make space for open dialogue and healing. The collaborative artworks made during their protests are in the permanent collections of The NY Historical Society, The Museum of the City of NY, and MOCADA. His writing has been featured in publications such as The Independent, Newsday, and Honeysuckle Magazine. He has most recently completed an artist’s residency with Localhost Gallery and partook in a photography installation at Cornell University. He is currently a 2022 artist in residence at Socially Distant Art. In the Spring of 2022, Ciarán opened an alternative art gallery and multipurpose creative space in the East Village called All St NYC. He holds a masters degree in Media Studies from the New School and is adjunct faculty at NYU Tisch’s IMA undergraduate program.