Digital America interviewed Cat Bluemke in April of 2025 on her work GAN of Living Skies.

:::

:::

Cat Bluemke: The traditional North American landscape painting tradition has a deeply colonial approach where the land is portrayed as either empty or wild, in both cases ripe for settlers to come and “tame” it. I was struck by the stark contrast between the serene landscapes of the Hudson River School or Canada’s Group of Seven and the brutal reality of westward expansion occurring simultaneously at this period in history. I was living in Saskatchewan, Canada (Treaty 4 territory), when I first began the GAN project. The painting traditions that had depicted this region had been weaponized generations before by the Canadian Pacific Railway to encourage European settlement and displace Indigenous populations. Part of my family had entered North America this way, as farm workers participating in the westward expansion made possible by the technology of the railroad and brutal colonialist policy. When I began conceptualizing the GAN project in 2019, I wanted to introduce a new kind of observer into the landscape-viewer dynamic. An observer that wasn’t human, but of a different kind of intelligence. An intelligence that would lead to broader questions about agency and the rights of the land that it relied upon.

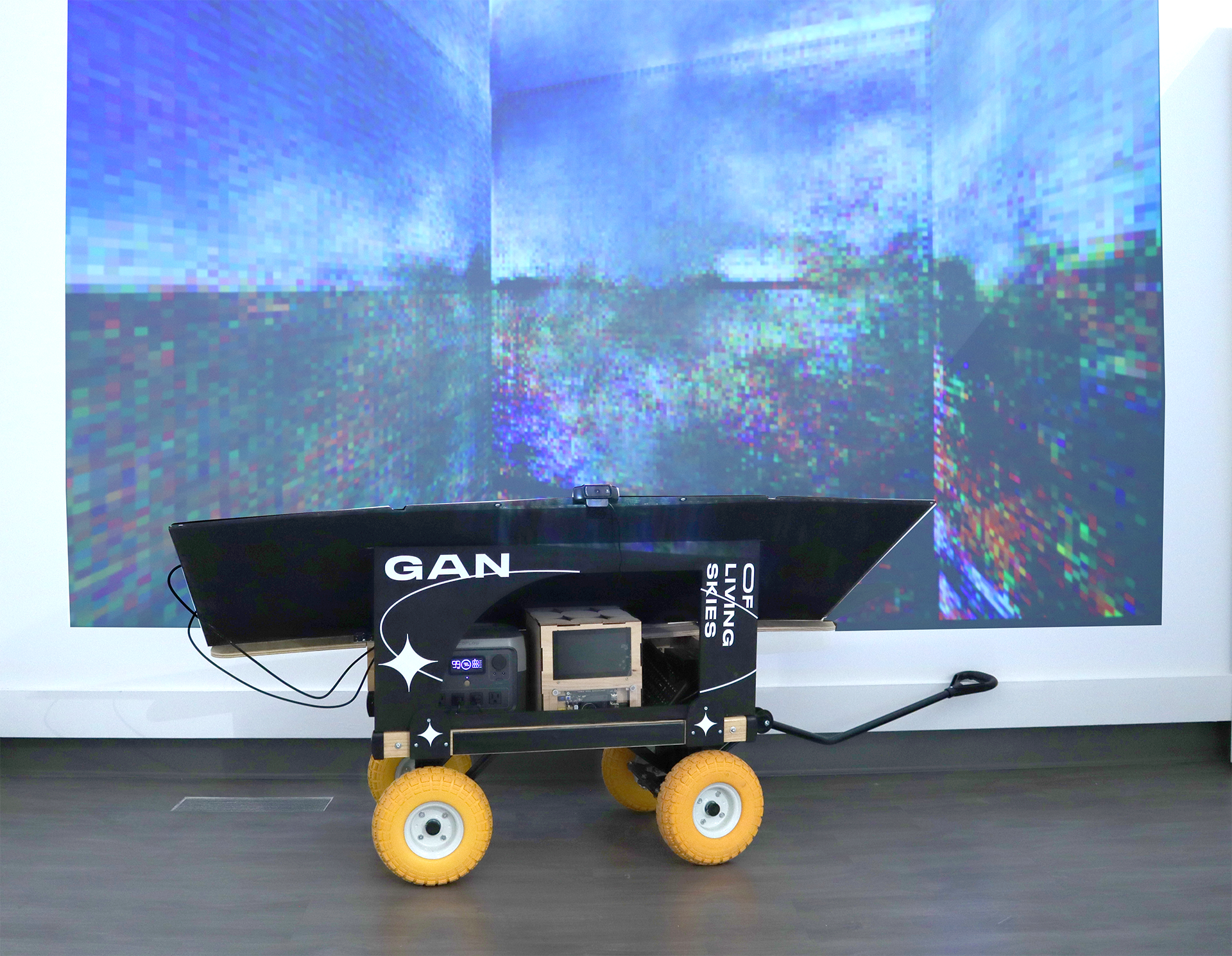

As digital artists, we’re still completely dependent on the natural world and its resources, even when we create in virtual spaces. I wanted to make that dependency explicit with GAN, building a system that literally cannot function without the direct support of the environment it observes. The sun powers the system that creates the images of the landscape, establishing this reciprocal relationship.

GAN moves through the land like a good camper, leaving nothing but footprints, taking nothing but photographs. Except in this case, the photographs become something new, a vision of the landscape that’s neither entirely human nor entirely machine.

DigA: How did you conceptualize both the mechanistic approach and the theoretical approach to the work? What was your creation process?

CB: My conceptual approach was really influenced by emerging conversations around beyond-human agency and intelligence. As my first AI-focused project, I wanted to explore what this new kind of intelligence might mean when given a specific creative role.The process involved a steep learning curve. I spent many hours on Reddit learning about both machine learning and solar power basics. The WaGAN, what I call the cart housing all the components of the GAN project, began as a scrappy wheeled battery charging station. It looks better now in its second iteration.

What mattered most to me was the process of creating a tool that would have a reciprocal relationship with its environment. I was interested in bringing a new kind of actor onto the stage of landscape interpretation, one that depends directly on the landscape it’s depicting. I believe there’s value in granting elements of agency to our technologies. After all, our tools emerge from our interactions with the environment, which itself deserves respect and reciprocity.

DigA: The WaGAN—the mobile computer and solar powered charging station— is solar powered. What do you hope to communicate about the massive amounts of resources used for generative AI?

CB: As a digital artist, I’ve found it too easy to disconnect from the physical impact my practice has on the world. The GAN of Living Skies project creates these moments of pause and reflection about resource use. While there’s much debate about exactly how resource-intensive generative AI is, we can safely assume most systems aren’t running on renewable energy like my little solar-powered WaGAN.

I see many valuable applications for AI, but its rapid integration into nearly every aspect of daily life concerns me. I value error, exploration, and the unexpected as key components of my art practice and human intelligence. GAN of Living Skies isn’t sophisticated as machine learning goes, but it’s not meant to be. Instead, if you encounter this strange WaGAN in a sunny field, I want it to inspire you to reflect on our broader relationship with AI and its environmental footprint.

DigA: The resulting images from the WaGAN are neither entirely human or machine. How do you categorize the images? Do you consider the images the work?

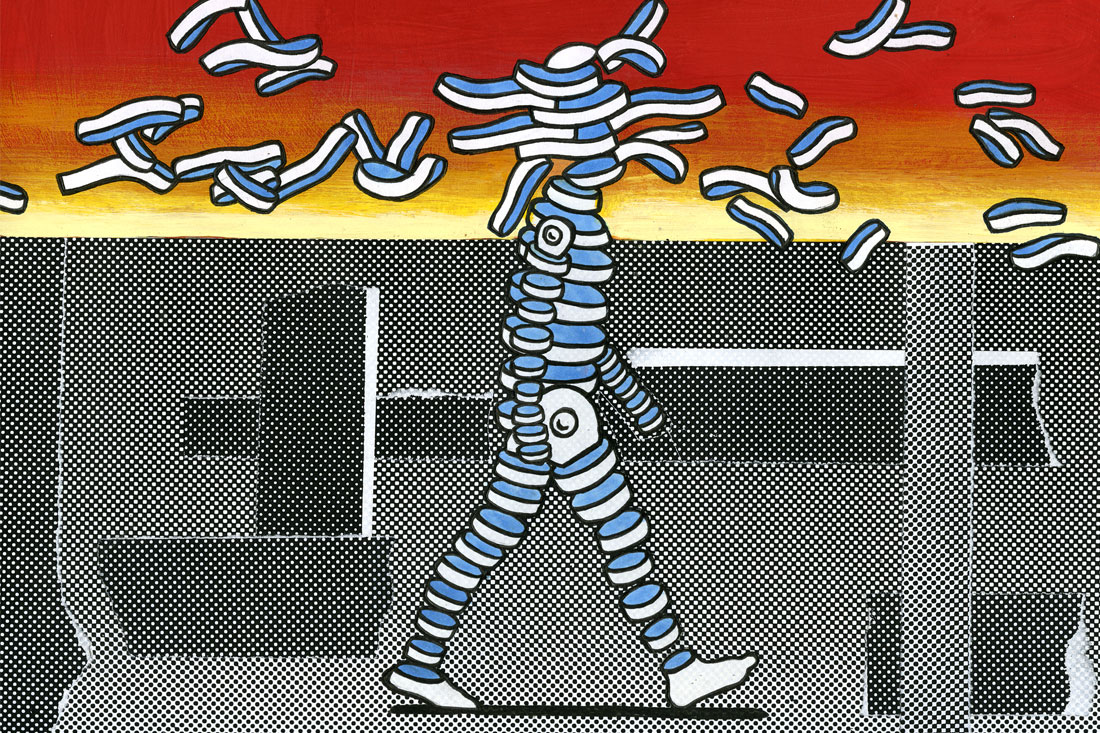

CB: I think of GAN as kind of an artificial “Sunday painter”, which is this unfortunately dismissive label for hobbyist painters who create pleasant landscapes or still lifes. I see GAN in that tradition, but with a twist!

For me, it’s not really about the images themselves, it’s about the practice. My artistic output becomes the act of fostering GAN’s creative capacity: taking it out for strolls in nature, updating its components, or maintaining its systems. The relationship is what constitutes the work.

When exhibiting the project, I’ve approached it in different ways. Sometimes I’ve shown the training dataset alongside GAN’s output as a two-channel video installation. Other times I’ve displayed the physical WaGAN contraption with a projection of its image output nearby. During the 2023 exhibition, I added a live performance element where I took GAN from its gallery installation out for a walk with the audience, and we all watched it work in real time.

I’ve come to think of GAN as a collaborator, a non-human partner I need to nurture and provide opportunities for. And our collaboration is ongoing!

DigA: Your work often uses digital pathways to comment on physical things. This is seen in works such as Gameworkers and Guildworkers (2020), which uses the video game construction to analyze the working conditions of builders, and Parked Domains(2016), which emphasizes buying cyber space. What is the connection between digital and physical that intrigues you?

CB: Computers and the internet fascinated me since childhood because they offered access to a world beyond my physical limitations as a young suburban girl. I was fortunate to experience the internet through message boards before social media became dominant. Part of my artistic practice comes from that idealistic kid inside me who’s always questioning why we recreate real-world limitations in digital spaces when we could be creating something completely new.

The projects you mentioned both engage with the history of technology. “Gameworkers and Guildworkers” explores connections between medieval cathedral builders and modern game developers, while “Parked Domains” investigated the dot-com bubble. I’m drawn to how technologies reshape society’s norms and expectations over time, and by highlighting different histories I hope to propose new futures. Like I said, I’m still an idealistic kid! That’s probably why I favour using computers and video games in my work, while I still venture out to explore new media when it makes sense for the project.

With AI advancing into so many aspects of daily life, there’s much up for discussion around current limitations and norms. From government policy to grassroots activism, AI will shake up the status quo. Though I’m cautious about its resource demands, I recognize its potential impact on both digital and physical realities. I hope to keep exploring these intersections in ways that are both playful and critical.

DigA: What are you working on next?

CB: I’ve still got a few updates for GAN in the works. In June I’m taking the WaGAN to Dawson City, Yukon, at a residency with the Klondike Institute of Art and Culture. I plan on rebuilding the software and image database, training GAN on the incredible Subarctic landscape. I’ll be catching the summer solstice, meaning near-constant daylight and working hours for GAN. While GAN will be catching some midnight rays, I’ll be sticking to a regular 9-5 schedule.

Aside from GAN, I’m in the midst of building out a large greenhouse/display structure for my Ornamushrooms project. I began this project during a residency at the Lunenburg School of the Arts in a coastal Canadian community in 2024-25. The project uses 3D modelling and 3D printing to promote the growth of edible mushrooms on wooden heritage homes in the area. The project probes the tension between heritage preservation and the urgent need to reimagine our domestic spaces amid overlapping crises of food insecurity, housing accessibility, and climate change. I find myself collaborating with another beyond-human intelligence in this project, but with edible results!

:::

Check out Cat Bluemke’s work GAN of Living Skies.

:::

Cat Bluemke is an artist working primarily in game design, expanded reality, and performance. Previously working collaboratively as SpekWork Studio and Tough Guy Mountain, she creates games, performances, and immersive experiences that explore technology’s ability to obscure the line between work and play. Her work has been exhibited internationally with prominent institutions including Rhizome and the New Museum (2020) and the Venice Architecture Biennale (2018) as part of the American pavilion’s corollary exhibits. Recent exhibitions include the Lunenburg School of the Arts (2025), Fotomuseum Winterthur (2024), the Milan Machinima Festival (2024), the Singapore Art Museum (2023), Art Gallery of Regina (2023), and the Art Gallery of Grande Prairie (2022).