Digital America interviewed Andy DiLallo in April 2022 about his piece Steal this Sticker (2022) and multimedia art.

:::

DA: Most of your work is interactive, meaning the viewer takes a participatory role in the art experience. What aspects of interactive, or participatory, art excite you? What was the first piece you explored in a participatory nature?

AD: What excites me about interactive art is it allows us to engage with a creative idea in a tactile way. These works invite active participation in the world the artist has built rather than viewing it passively from a distance. In the traditional arts, this distance between the viewer and the art object is the standard convention, and it suppresses the embodied urge to move and touch, to use other senses outside of the gaze. I think interactivity seeks to close some of that distance by recognizing the agency of the viewer. My earliest experience of participatory work was probably through improvising with others as a musician. I eventually went on to study music as an undergrad, where I started exploring electronics and computer programs that augment or extend compositions. I distinctly remember performing Pauline Oliveros’s Sonic Meditations, which were simple text instructions that helped launch my investigation into listening as a form of activism.

DA: I found Steal This Sticker a very calming experience. The slow, melodic feel makes me feel relaxed while portraying an important theme of social activism. How do you strike a balance between slowness and impact in your work?

AD: I think the slowness is the intended impact in many ways, but it took me a while to fine-tune this approach in Steal This Sticker. The project initially started with me wheat pasting posters around town that said “REST.” in big letters and a QR code playing calming music when scanned. I moved on from that version as it increasingly felt necessary to explore the cultural factors we take for granted that make rest difficult. How can we slow down if the accepted expectation of our jobs, families, and society is to push us to earn more and spend more continuously?Meanwhile, we’re surrounded by a sense of existential precarity in the rising cost of housing, healthcare, education, etc., and a deteriorating social safety net. The directive “REST.” is perhaps not as effective without a deeper cultural analysis that positions it within a larger context, beyond the scope of what one individual alone is capable of doing. I’ve come to understand this as civic mindfulness, framing personal struggle within the larger sphere of our shared vulnerabilities and mutual interdependence. I tried to balance slowing down for the sake of slowing down with an awareness of systemic issues, encouraging people to take the time to sit with any shared livable vision of the future, let alone one centered on care.

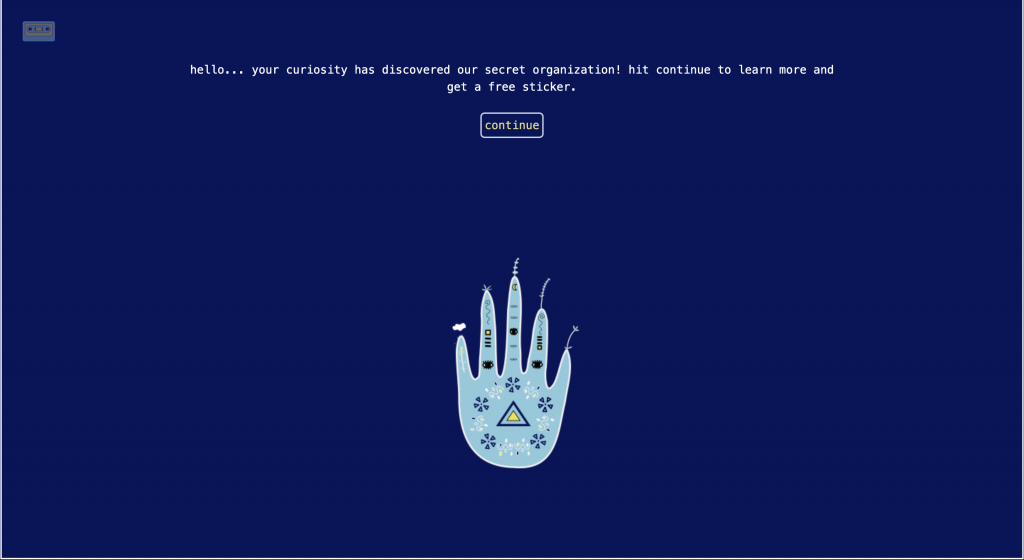

DA: There’s a retro style to Steal This Sticker that reminds me of old Pokemon games. Are there particular video game series, or other cultural sources, that inspired you for this piece? And further, was this slow reveal of text done purposefully to try and keep the viewer’s attention?

AD: I am inspired by street art, the idea of using art and sound as resistance, and the effects of tech on our culture. While thinking about ways to synthesize these elements, I discovered the sound theorist Brandon LaBelle’s book titled Sonic Agency: Sound and Emergent Forms of Resistance.I was particularly interested in one chapter where LaBelle talks about revisiting the more revolutionary and intersectional aspects of 1960s and 1970s political culture. A vision thoroughly absorbed and commercialized over the years by unchecked capitalism, packed into neoliberal notions of individual liberation backed by the self-help industry and watered-down new age sentiments. LaBelle’s writing opened the door for me to speculative play and remix as a form of reappropriation and world building, which led me to think about a game as an excellent framework to test these ideas.

Fiction books also have a tremendous impact on my creative process and tend to work their way into my projects. Infinite Jest by David Foster Wallace and Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying OfLot 49 were big inspirations for me while working on Steal This Sticker. In Infinite Jest, I became transfixed by his concept of mass dissemination of a film so pleasurable you can’t stop watching it until you die. In some ways, the real-life equivalent of that is everyone constantly staring at their phones. Walking through campus, I see this every day and think to myself, “wow,DFW really nailed it.” The book probably also contributed to the somewhat subliminal calming aesthetic and participatory dissemination aspect of Steal This Sticker. The Crying Of Lot 49 is about a subversive countercultural mail courier service. Using physical mail to send messages and information is quite possibly a radical act these days, slowing down the overwhelming amounts of information available to us at our fingertips. In the early stages of testing the game, the slowness of the text was quite divisive, appreciated by some, but also a common complaint from other friends. One person called it “frustrating.” I purposely made the text slow, not so much to keep people’s attention but to confront the expectation that anything worthwhile needs to happen immediately. It’s particularly uncomfortable within a culture that measures success by one’s productivity and efficiency at every moment of the day.

DA: How have people’s interactions with the piece differed? What had you expected, and what has surprised you most?

AD: I think I’m surprised by the wildly divergent reactions to the piece. So many folks take one look and write it off as a stylistic cliche, naive, or overly didactic and don’t take the time to play it. In contrast, others see work like this as a relevant and vital form of protest art. That polarization has highlighted how this piece tests the limits of the traditional graduate fine art world I’m in and what is considered a legitimate making practice in the academic space. Steal This Sticker doesn’t cater to the art school aesthetic that emphasizes the individual, the object, and value within the speculation-driven art market. Instead, it’s about community-building and conversations at the grassroots level, aligning with a long history of interventionist and activist artworks, often absent from the conventional canon. Steal This Sticker demands both cultural analysis and cultural action. I was pleasantly surprised when people started stealing the physical sticker off of street locations and even the door to my studio! I guess I invited that kind of participation with the piece’s title and vibe. It’s been great to see people interpreting it that way.

DA: Can you share with us a bit about what you’re working on now?

AD: One of the projects I’m excited about is with a local non-profit called Junkyard Social Club. They are a community space for play and experimentation with a large playground made entirely from repurposed junk. We are teaming up to create an interactive audiovisual junk sculpture called TRASH+TECH. It’s an installation where people touch a large-scale interface made of trash and old cathode ray tube TVs, watching it all light up via projection mapping. They see animations flutter across the TVs mounted to the wall and facilitate a musical composition through the TV’s speakers. I’m interested in what happens when we use technology to regenerate discarded objects instead of the endless search for the new that inevitably produces a culture of waste. The idea I’m testing is whether play can help re-contextualize technology through a restorative lens instead of an extractivist one. Ultimately, the piece aims to build transgressive digital literacy, an awareness of ourselves as digitally or technologically augmented beings, empowering people, especially kids, to navigate this new reality we’ve thrust ourselves into incredibly fast, considering the larger arc of human history.

:::

Andy DiLallo is a media artist exploring restorative uses of technology through interactive and immersive experiences, video games, net art, video art, and sound art. He is currently an MFA Arts Practice candidate at the University of Colorado Boulder. Andy’s work was recently featured internationally at SIGGRAPH 2020, the 2021 Athens Digital Arts Festival, and a public intervention during COP26 Glasgow.